The anthropomorphic stone obelisks of Artsakh

Anthropomorphic stone obelisks are a crucial component of Artsakh's pre-Christian culture. They were not adequately examined and analyzed during the Soviet era for well-known reasons (Petrosyan 2010, 137-148). Moreover, existing studies have been politicized.

Several Azerbaijani researchers have depicted and identified Artsakh's anthropomorphic stone monuments as Caucasian Albanian, attempting to interpret their prevalence, particularly in Artsakh, as the presence of an Albanian ethnocultural substratum (Khalilov 1987, 22; Vaidov, Geyushev, Guliyev 1974, 446-447).

Hence, scientific research on these obelisks, including an examination of their precise chronology and ethno-cultural affiliation, is particularly vital, as it allows for the scientific rejection of Azerbaijan’s forgeries (Petrosyan, Yeranyan, 2022).

Although specific obelisks were discovered in the 1960s, their technical, iconographic, and semantic examination, chronology, and possible ethnographic issues remained unexplained, if not merely unsolved. As a result of Artsakh's liberation war, new opportunities for studying the region's ancient history and culture arose. The physical accessibility of the anthropomorphic obelisks was a crucial circumstance in allowing for comprehensive description, measurement, and photography, in addition to research into the historical and cultural environment.

Iconography

These monuments are rectangular, flat longitudinal anthropomorphic slabs with the human body as the main axis of composition, with all other components acquiring iconographic and conceptual value in that context. These slabs are divided into three sections by two horizontal grooves, emphasizing the three parts of the body: the head (which takes up nearly a third of the monument), the torso, and the underbelly (Figs. 1-5). The monuments are approximately 30–60 cm wide, 120–140 cm high, and 20 cm thick, with some reaching up to 2 meters in height. All of the known examples are made of limestone (Yeranyan 2020, 246-252).

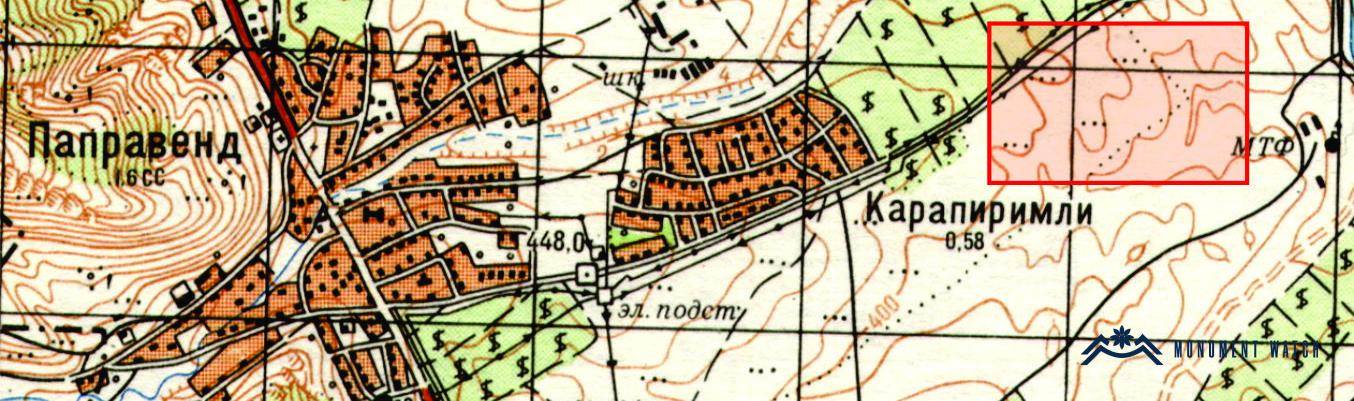

Topography

According to available data, there are currently over thirty monuments, the majority of which are located in a relatively closed region of field or steppe, in the longitudinal area that connects the highlands and the steppe of Artsakh, stretching nearly 30-40 km. These obelisks can be seen accumulating around Tigranakert in Artsakh, as well as Gyavurkala settlement and Nor Karmiravan village, which is not far from the latter, and some of them were relocated to the Artsakh State Historical-Geological Museum (Stepanakert) and Martakert Historical-Geological Museum and placed in the yard during the Soviet period. The studied region is located in the southeastern part of the Lesser Caucasus. It encompasses the western half of the Kur-Araksian plain, the eastern part of the Artsakh steppe, and the west of the Mil steppe, which lies east of it.

Chronology

When discussing the date and function of the monuments, it is important to note that only one group of over 30 monuments was discovered in its natural environment (in situ), which significantly complicates the problem. However, it is worth noting that excavations conducted in 2016 in the vicinity of the anthropomorphic obelisks discovered in Nor Karmiravan village of Martakert region revealed that the majority of them are located in the natural environment of their construction, on the tomb (Figs. 6, 7). The archaeological material discovered in the tomb dates back to the 8th–6th centuries BC (Fig. 8), which is also the most likely date for the obelisks.

Function

After examining the available data, we can conclude that the stone obelisks discovered in Artsakh were most likely tombstones or cult symbols that were placed on the top or center of the burial site with or without a pedestal, as well as on funerals. Many times in recent years, particularly after the second Artsakh war, some Azerbaijani specialists have criticized not only the approaches and ideas related to obelisk research but also the fact of studying them and conducting excavations around them in general.

According to official sources, they even applied to the Prosecutor's Office of Azerbaijan to initiate a criminal case against those who excavated in the area of Nor Karmiravan village of Martakert region around these stones (https://apa.az/az/incesenet-haqqinda/Arxeoloq-Arsax-sozunun-Dadivng-monastirinin-v-Xacin-knyazliginin-ermnilr-qtiyyn-aidiyyti-yoxdur-colorredMUSAHIBcolor-615839?fbclid=IwAR2cyHo3wbk7WEvREeamlPNUTUribGlonaSb4n-xd6cU_y19QMZvPwVYz30).

We think it is crucial to note that during the research and excavation of these obelisks in Artsakh, all laws of the Republic of Artsakh were followed, the excavations were carried out at the request of local authorities, and the results were processed following all professional methodological principles. Azerbaijani researchers' destructive behavior suggests that they lack scientific interest in obelisk research and that political inopportune approaches are more important to them.

Given that the majority of those obelisks remained under the control of the Azerbaijani armed forces after the tripartite declaration was signed on November 10, their future fate is uncertain.

Bibliography

- Petrosyan 2010–Petrosyan H., Cultural ethnocide in Artsakh (mechanism of extortion of cultural heritage), state terrorism of Azerbaijan and the policy of ethnic cleansing against Nagorno Karabakh, Shushi, pp. 137-148.

- Petrosyan, Yeranyan 2022-Petrosyan H., Yeranyan N., Monumental Culture of Artsakh, Yerevan.

- Yeranyan 2020 – Yeranyan N. 2020, Main Results of the Study of Anthropomorphic Stelae in Artsakh, Archaeology of Armenia in regional context, Yerevan, 246-252.

- Vaidov R. Geyushev R. Guliyev N.- New finds of stone obelisks in Azerbaijan, Archaeological Discoveries of 1973, Moscow," Nauka", 1974, pp. 446-447.

- Khalilov M. Stone statues of Azerbaijan (IV century BC-VI century AD), Author, Canditate of Historical Sciences, Yerevan, 1987, page 22.

The anthropomorphic stone obelisks of Artsakh

Artsakh