The monastic complex of Gtchavank

Location

Gtchavank is located 1.8 kilometers northwest of Togh village in the Hadrut region of the Republic of Artsakh, in the concavity of the northwestern slope of Toghasar, or Chgnavor, mountain. Historically, it was part of the Myus Haband province of Greater Armenia's Artsakh province. It is currently occupied by Azerbaijan (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1 The general view of the Gtchavank monastic complex, photo by H. Petrosyan.

Historical overview

The monastery's history has been documented since the early middle Ages. According to the Armenian Catholicos Yeghia Archishetsi's paper, the abbot of Gtchavank also attended the Ecclesiastical Assembly held at Partav in 704. ("Gtay vanats monk," Hakobyan 1981, 150; Kaghanakvatsi 1969, 233). The monastery also functioned as the bishop's residence. The fortress built above it was named Gtich after the monastery that served as Yesai Abu Muse's residence in the 9th century and the heart of the new kingdom created in Dizak in the 10th century (Mkrtchyan 1985, 84).

During the reign of the Dizak Meliks, particularly Melik Yegan, the monastery flourished (the first half of the 17th century). Inscriptions from the 13th to 17th centuries preserved on the complex's walls provide vital information about the province's rich medieval past. The inscription on the northern wall of the main church indicates that the monastery's main church was built in 1241–1246 by the bishop brothers Sargis and Vrtanes of Amarasi. (Hakobyan 2009, pp. 91-92.)

Gtchavank also became a cultural center in the 15th century. It featured a Scriptorium, which held several famous manuscripts. Sayun, a Togh villager, renovated the dome of Gtchavank's main church in 1717. Melik Yegan appointed Bishop Mesrop as abbot of Gtchavank in 1723. In the nineteenth century, Arakel Kostandyants, the abbot of Gtchavank, produced a historical and ethnographical study that Raffi incorporated into his book "Khamsa's Melikdoms." In 1913, a part of this manuscript was published in Vagharshapat under the title "Dizak's Melikdom." Matenadaran holds the whole manuscript.

The earthquake in 1868 destroyed the single-nave church. Gtchavank was abandoned and deserted after the domed church was wrecked.

Architectural-compositional examination

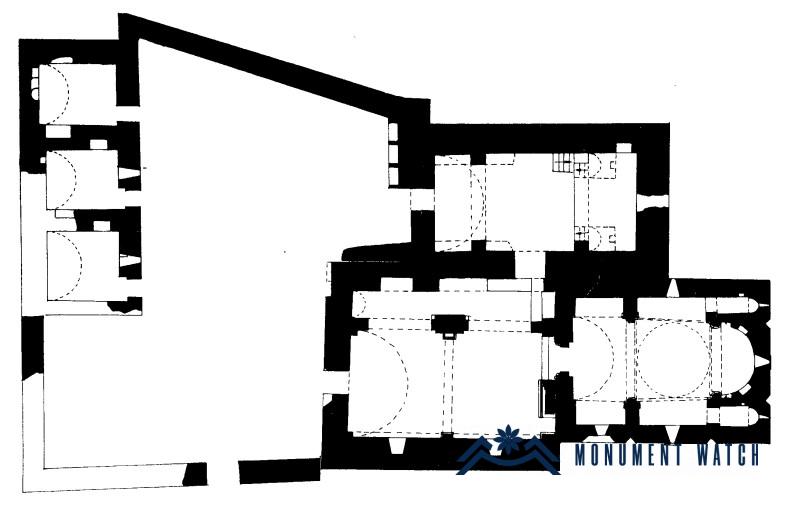

The main church, the gavit attached from the west, and the single-nave church built from the north comprise Gtchavank's monastic complex. The remnants of residential buildings and the battlement have been maintained to the west of the main buildings (Fig. 2). Khachkars and stele inscriptions abound in the complex. The Gtich monastery's manuscripts have been preserved. The cemetery extends all around the monastery, the majority of which has been ruined. There are very few tombstones buried in the earth, and the majority of them are covered with soil. Khachkars are lying on the ground.

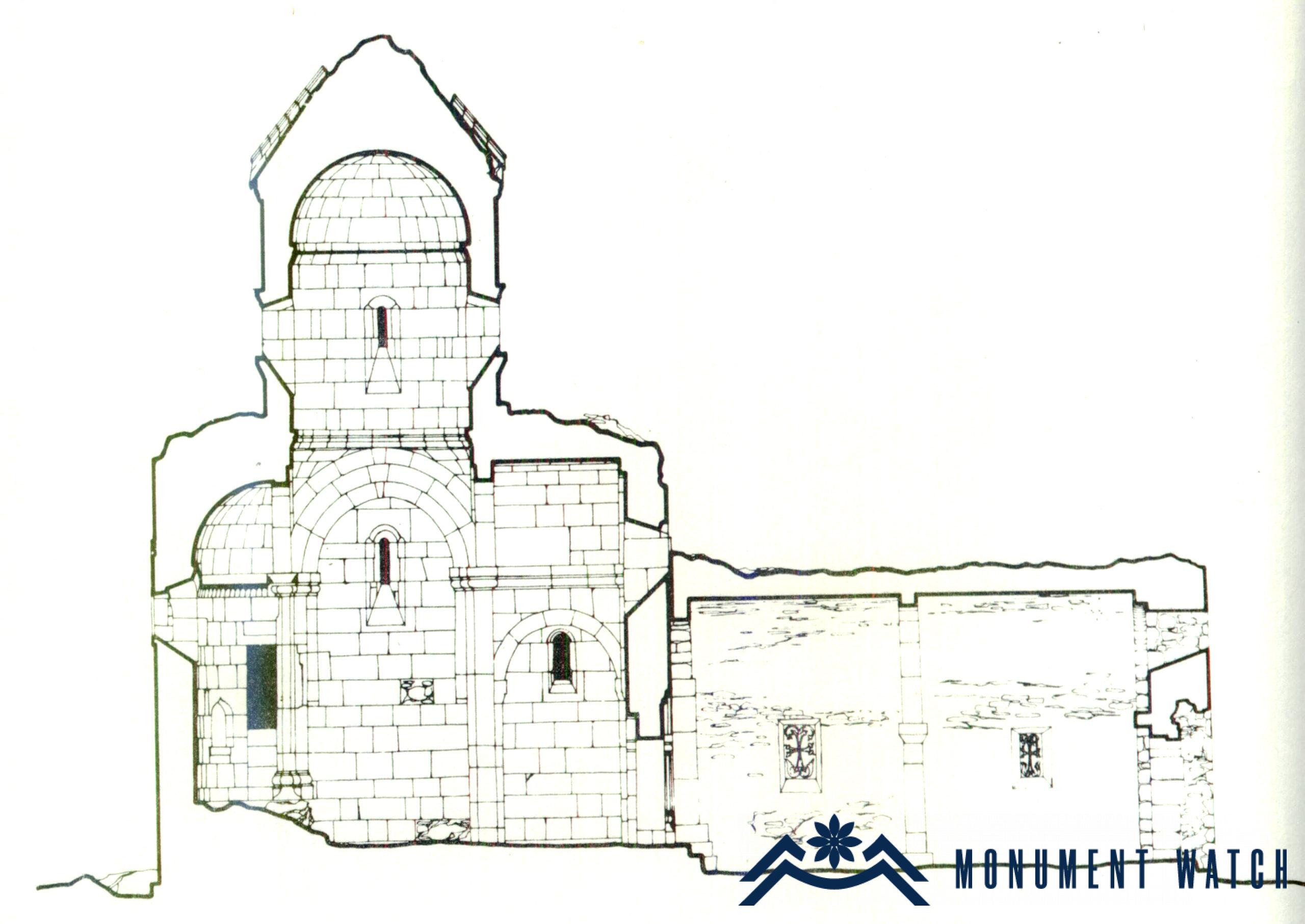

The church is a domed hall of average size (size: 10.0 x 7.5 m, Fig. 2). The prayer hall concludes in the east with a semi-circular high altar, flanked by elongated, double-storied sacristies on the south and north sides. These are rectangular, vaulted, and contain small niches on the eastern side. The prayer hall leads to the sacristies on the first floor, and stone steps lead to the sanctuary on the second floor. The dome-supporting arches are held by the wall pilasters of the prayer hall's southern and northern walls, as well as the original walls of the high altar. The wall pilasters are linked together by arrow-shaped arches. Pendentives carry out the transition from the square under the dome to the dome (Fig. 3).

Fig. 2 The general architectural plan of the complex, the measurements by M. Hasratyan.

The main church's solitary entrance is on the western façade, and it opens into the gavit adjacent to it. Its rectangular opening is set into a finely built porch. The latter's double arch of semi-cylinders rests on semi-column beams with hemispherical basements and capitals. Similar porch solutions can be seen in the porches of 10th–11th century Armenian architecture, particularly in Shirak churches (Hasratyan 1992, p. 63).

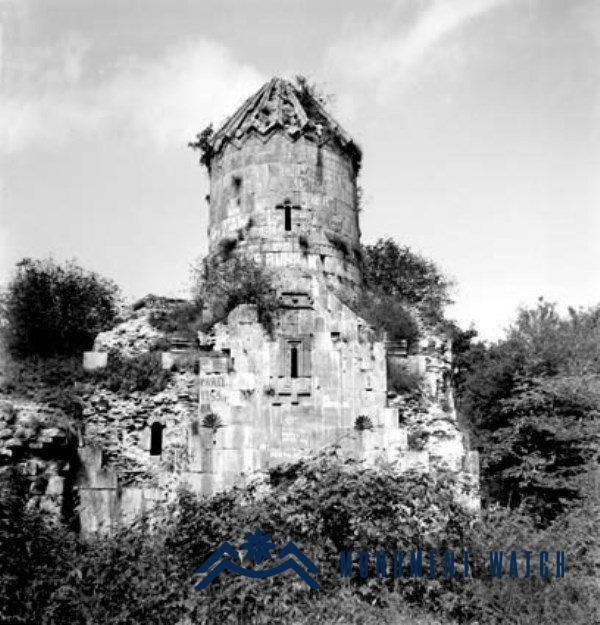

The decorative characteristics of the church's exterior architecture are the pair of triangular wall niches adorned with beam-shaped cuts on all facades (excluding the western one) and the windows fringed with wide platbands installed in the flatness centers (fig. 4). Some of the decoration's themes have equivalents in the arch crowns of the Gandzasar church's niches (Mkrtchyan 1985, 86). The dome is cylindrical and crowned with a hand-fan-shaped spire (fig. 5). Its height (the drum and the spire combined) matches the height of the church's main volume and is the dominating element of the entire building. To minimize the height of the drum, medieval craftsmen wrapped a large area around its circumference.

The hand-fan-shaped roof reflects the classic form of the 10th–11th century and is typical of Bagratuni era Armenian churches. The dimensional composition and details of Gtchavank's main church resemble those of Ani-Shirak's architectural monuments. This was something Leo noticed once (Leo 1885, p. 247).

Similarities can also be seen inside the church. The bema wall of the tabernacle features a geometric bas-relief displaying protuberant diagonals and hexagons on a background of deeply carved triangles.It resembles a unique mosaic. Similar solutions can be found in the porches and bema walls of the main churches of 13th century monastic complexes (Makaravank, Hovhanavank, Saghmosavank, Aghjots Monastery, etc.). The cornice on the front wall of the Gtchavank stage is quite unique in architectural solutions. It features a section with stylized pomegranate sculptures (fig. 6).

The church is made of clean, polished white felsite stones.

The gavit was linked to the main church from the west, slightly off the longitudinal axis. It is a rectangular hall that runs west to east. A pilaster in the northern part divides the hall into a big southern and a small northern section, both of which are vaulted. The northern corridor-shaped section, with a pair of arched entrances, faces the gavit's larger side. The entrance to the second church of the Gtchavank complex is located in the northeast corner of the corridor. Similar unique solutions to the gavit can be found in Syunik monuments dating from the early 10th–11th century (Gndevank, Vahanavank, Karakop) (Mnatsakanyan 1952, pp. 24, 25). These primarily refer to early dating examples of gavits.

Fig. 3 Longitudinal section of the main church and gavit, measurements by M. Hasratyan.

Fig. 4 The southern facade of the main church, photo by H. Petrosyan.

Fig. 5 The Gtchavank complex, from the south, photo by H. Petrosyan.

Fig. 6 The bema wall of the main church, photo by H. Petrosyan.

Fig. 7 The khachkar bearing the construction inscription, photo by H. Petrosyan.

Inside the gavit, adjacent to the western wall of the church on the right, there is a carved khachkar that was raised in 1246 by one of the brothers who built the church, Ter Vrtanes. As the inscription says, "I, Ter Vrtanes, raised this cross for the salvation of my soul in 1246." (CAE 5, 184). Khachkar's frame is wide and rectangular, consisting of semi-cylinders and slabs (fig. 7). On the left side, a second similar khachkar was raised, which is today maintained in Etchmiadzin's Mayravank. Both are outstanding pieces of art that depict the Second Coming of the Cross and the Righteous Judgment (Petrosyan 2008, 156-157).

The gavit was also used as a mausoleum for Armenian nobles. There are lace frames and typographic tombstones among the tombstones kept here. The courtyard was constructed using rough basalt stone and lime mortar.

The second church of Gtchavank is linked to the primary church and gavit by the southern wall. It features a rectangular vaulted hall from the layout. The roof fell, and the upper portions of the side walls were damaged (fig. 8). The prayer hall concludes with a rectangular tabernacle. It is vaulted and separated from the prayer hall by a broad arch. The use of single-nave churches with a rectangular tabernacle is typical of Artsakh ecclesiastical architecture from the 12th–13th centuries, and it flourished in the late middle Ages as well. Similar architectural solutions can be seen in the churches of Dadivank, Gtchavank, "Bri Eghtsi", Yeghishe the Apostle, Karmir Kar, Charektar, Khatravank, "Okht Eghtsi" monasteries, Koshik anapat, and other complexes. Four of Handaberd Monastery's five churches contain similar compositions (Petrosyan et al. 2009, 31–34). Another unique characteristic of the church is that the pair of sacristies on the eastern side, adjacent to the church's southern and northern walls, are not located on both sides of the tabernacle (as appropriate), but beneath the floor of the tabernacle and have a staircase entrance from the prayer hall. According to M. Hasratyan, this is an exceptional and rare phenomenon in Armenian architecture (Hasratyan 1992, p. 66).

This church of Gtchavank lacks decorative elements like the gavit. The entrance is the only decorative area. Only one of the three khachkars enchased above the arched entrance has been preserved. A khachkar was utilized as a lintel stone. There are numerous examples of such khachkar reuse in Artsakh's medieval architecture. They are sometimes used to embellish building exteriors (Handaberd Monastery) and surfaces (Bri Eghtsi).

Like the gavit, this church is made of rough, unpolished basalt stone and lime mortar.

The building remains of the residential chambers and the battlement wall have been maintained on the western side of the Gtchavank sacred structures.

Fig. 8 The Gtchavank monastery, from the west, photo by H. Petrosyan.

Bibliographic examination

Gtchavank is one of the complexes that has received the least amount of professional research. Sh. Mkrtchyan addressed the history of the monastery's foundation and briefly presented its individual buildings and khachkars in his monographs dedicated to Nagorno Karabakh's historical and architectural monuments (Mkrtchyan 1985, 84-87; Mkrtchyan 1988, 67-71; Mkrtchyan 1989, 67-71). In his work dedicated to the Artsakh School of architecture (Hasratyan 1992, 62–67), M. Hasratyan made a professional reference to the Gtchavank complex. The monastic complex is mentioned briefly in V. Harutyunyan's book on the history of Armenian architecture (Harutyunyan 1992, 339,340).

The condition before, during, and after the war

Gtchavank has always been difficult to reach due to its location. However, it should be noted that it is also one of the most visited complexes. During the Soviet era, many visitors left their imprints on the complex's walls, both inside and outdoors. The structures have been vandalized with messages made with coal and paint in several languages. The second single-nave church in the complex is in a critical state. The roof collapsed. The upper sections of the side walls were broken. A large fracture has emerged on the eastern and western facades, threatening the structure's integrity and stability. During the Soviet era, the main church and the gavit were mostly intact. The roofs had been damaged. The complex was not severely damaged during the first Artsakh war. From 2005–2007, Gtchavank restoration work was completed according to architect Mary Danielyan's plan (fig. 9). The main church's spire and vault, as well as the roofs of the crucifixes and the gavit, have all been repaired. The restoration process is yet incomplete (Fig. 10). The complex's second church remained half-destroyed. During the 44-day war, it did not change significantly. The current state of affairs is unknown.

Fig. 9 The Gtchavank monastery before restoration, photo by H. Petrosyan.

Fig. 10 The Gtchavank monastery during restoration, photo by H. Baze.

Bibliography

- Barkhutaryants, 1895–Barkhutaryants M., Artsakh, Baku.

- CAE, 5-Barkhudaryan, Corpus of Armenian Inscriptions, Institute of Archaeology and Ethnography of the Academy of Sciences of the Armenian SSR. Yerevan: Publishing House of the Academy of Sciences, Yerevan, 1982.

- Leo, 1885-Leo, My diary, Shushi.

- Kaghankatvatsi, 1969-Movses Kaghankatvatsi, History of the Caucasian Albania, "Hayastan" publishing house, Yerevan.

- Hakobyan, 1981-Hakobyan A., The newly discovered paper of Catholicos Yeghia Archishetsi, Historical-philosophical journal, N 4.

- Hakobyan, 2009-Hakobyan A., Historical-geographical and lithographic research (Artsakh, Utik), Mkhitrayan publishing house, Vienna-Yerevan.

- Hasratyan, 1992–Hasratyan, M., Syunik School of Armenian Architecture, NAS RA Publishing House of Armenia, Yerevan.

- Harutyunyan, 1994–Harutyunyan, V., History of Armenian Architecture, "Luys" State Publishing House, Yerevan.

- Mkrtchyan, 1977-Mkrtchyan Sh., Ecclesiastical and historical monuments of Hadrut region, "Ejmiatsin", III.

- Mkrtchyan, 1985-Mkrtchyan Sh., Historical and architectural monuments of Nagorno Karabakh, "Hayastan" publishing house, Yerevan.

- Petrosyan, 2008-Petrosyan H., Khachkar. Origin, function, iconography, semantics, Printinfo, Yerevan.

- Mkrtchyan, 1989-Mkrtchyan, Sh., Historical and architectural monuments of Nagorno-Karabakh/second edition/, "Parberakan", Yerevan.

- Mnatsakanyan, 1952-Mnatsakanyan S., Architecture of Armenian vestibules (gavits), Publishing House of the Academy of Sciences of the Armenian SSR, Yerevan.

The monastic complex of Gtchavank

Artsakh