The Surb Hakobavank manastery in Metsirank

Location

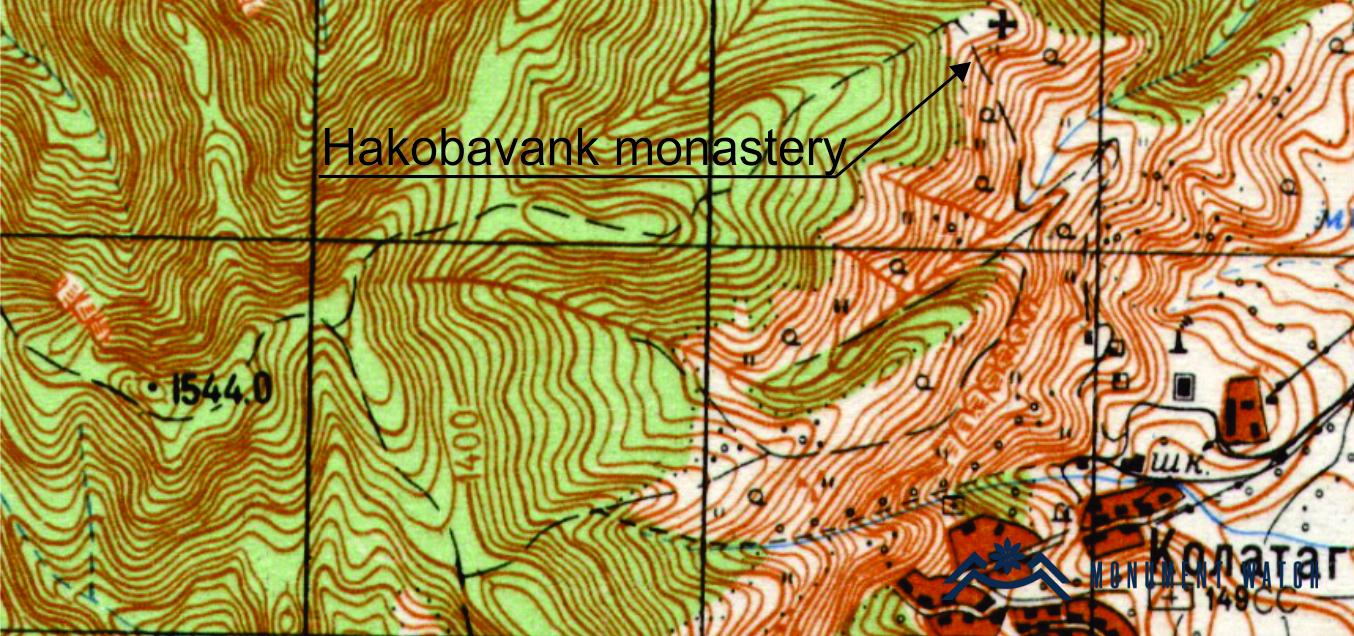

Hakobavank is situated in the historical Metsirank (or Metsarank) province of Artsakh, near the right bank of Khachenaget, on a wooded ridge 1.5 km north of Kolatak village, within the Martakert region of the Republic of Artsakh (Fig. 1).

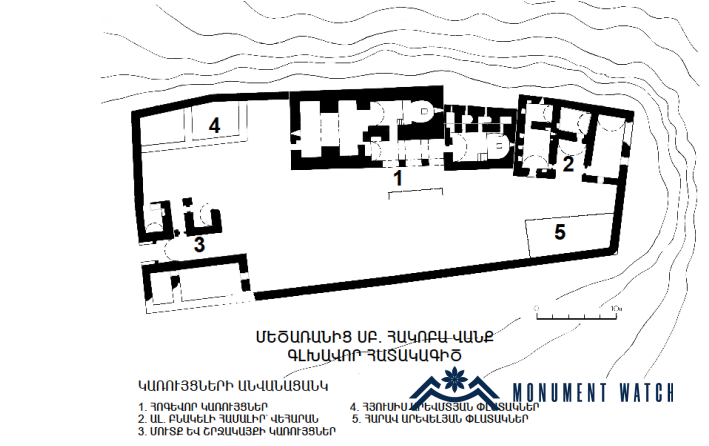

The primary layout of the monastery is rectangular and runs from east to west (Fig. 2). Fences encircle the entire area. The complex includes religious structures (the western and eastern churches, as well as the gavit of the western church) as well as residential and commercial structures. The latter are clustered in the west, surrounding the entrance, and in the east, while the churches are located adjacent to the northern wall.

Historical overview

Hakobavank stands as one of the renowned religious, educational, and cultural centers in Artsakh. The monastery derives its name from the esteemed patriarch of Mtsbin, St. Hakob, whose relic (right hand) is housed here.

Hakobavank held prominence as a well-known pilgrimage site, an episcopal center, and, for a certain period, the seat of a Catholicos. Despite limited information available in bibliographic sources, historical evidence is preserved in inscriptions found within the vicinity. These inscriptions detail the monastery's builders and subsequent reconstruction efforts. The oldest among these inscriptions is engraved on the plinth of a khachkar, later incorporated into the wall of a small church as a building block, dating back to around 853 (Petrosyan, Yeranyan 2022, 28). Among various inscriptions on the southern wall of the eastern church of the monastery, there is an inscription documenting the renovation of the church. "(1212) I, Khorishah, spouse of Vakhtang, lord of Khachen, daughter of the great Sargis, sister of Zakari and Ivan, rebuilt this church for the salvation of my soul in Metsarank"(CAE 5, 12) (Fig. 3). The inscription and the current state of the monastery make it evident that extensive rebuilding took place, encompassing both of its churches. Moreover, there is widespread evidence of the reuse of khachkars, inscribed slabs, and tombstones. Hakobavank underwent multiple reconstructions during the 17th and 18th centuries, as indicated by the inscription: "was restored in the 1140th year of the Armenian calendar (1691) by the hand of Bishop Grigor" (CAE 5, 11). Additionally, a construction certificate for one of the residential cells of the monastery dates back to the year 1725. The documented authentications, coupled with the current state of Hakobavank, enable a comprehensive understanding of the principal construction periods of the complex, spanning from the early 9th century to the late 18th century. Notably, the primary construction phases occurred during the 12th-13th centuries (Mkrtchyan 1985, 25). In addition to its religious significance, Hakobavank held a crucial role as one of the key educational and writing centers in Khachen. This is substantiated by records of several handwritten gospels compiled within the monastery (Voskean 1953, 90; Minasyan 2015, 22-23).

Architectural-compositional examination

The churches of Hakobavank are single-nave structures featuring vaulted semicircular tabernacles. The Eastern Church boasts an elongated structure measuring 7.80 x 3.20 meters. Positioned on the north side of the church are four chapels with an approximately square plan. Three of these chapels open into the prayer hall, while the fourth—known as the eastern sacristy—has an entrance from beneath the tabernacle. Additionally, the stage incorporates a vaulted tomb reliquary. Notably, due to these architectural features, the stage of the church is elevated higher than the typical design (Fig. 4). Access to this elevated area is possible only via stairs situated on the south side of the church. On the western wall of the church, as previously mentioned, there is an inscription indicating the renovation in 1212 (CAE 5, 12). The sole western entrance to the church leads into the hall constructed on this side. This hall features a distinctive three-arch colonnade on its south side, replacing the conventional front wall. Notably, the two columns and the arches connecting them and to the walls are finely hewn, a departure from the predominant use of rough-hewn stone in the construction of other buildings within the complex (Fig. 5). This architectural feature, with a three-arched opening, is also found in Koshik Anapat, Dadivank, and Tatev Monastery. The Hall of Hakobavank stands out for its abundance of khachkars, tombstones, and lithographic slabs. A distinctive and vibrant visual tableau unfolds with the juxtaposition of pink khachkars, gray tombstones, bluish walls, milky lithographic slabs, and an intricately carved sundial on orange limestone (Fig. 6). The inscriptions on the large, meticulously adorned tombstones reveal the final resting place of the Catholicoses "Ohanes...Arstakes...Simeon" (Fig. 7), as well as bishops "Simeon" and "Vardan" (Barkhutareants 1895, 171). These also witness the fact that Metsarank Monastery served as the seat of the Catholicos in the 15th century. Voskean also noted, "But centuries have passed since, due to political circumstances, and not for other reasons, the monastery of Surb Hakob was the residence of the Albanian Catholicoses, and from there they ruled their flock" (Voskean 1953, 88).

The western church extends along the entire northern length of the three-arched hall (Fig. 8). This church is a simple single-nave rectangular structure measuring 8.00 m x 3.4 m, featuring a vaulted hall. On the eastern side, the prayer hall concludes with a relatively deep semicircular apse housing a senior tabernacle, accessible via stairs from the southern and northern sides. A southern entrance connects the church with the three-arched hall, while a western entrance links it to a gavit chapel. The three-arched gallery-portico is a shared element between both churches and maintains the same height as them. This gallery seamlessly integrates into the three-dimensional composition of the churches, with the three-arched facade emerging as their principal facade (Fig. 9).

The gavit of the church is a pillarless, cross-arched structure featuring an almost square hall with dimensions of 7.00m X 7.6m. The interior showcases wall pilasters adorning the planes of the northern and southern side walls. Besides the spacious eastern opening, the gavit possesses an entrance in the southwestern section. The structure is illuminated by three windows, with two on the southern side and one on the western side. The northern wall, serving as the annex of the enclosure wall, is solid and lacks openings. An inscription on a khachkar integrated into the gavit wall dates back to 1212, while the front stone of the southern entrance of the second church bears an inscription from 1293. A total of 41 large and small inscriptions were discovered and documented within the monastery's grounds (CAE 5, 11-22).

The gavit, as evidenced by the tombstones on the floor, served a dual purpose as a tomb. The presence of these tombstones indicates the significance of the gavit as a burial space.

The damaged and partially ruined residential and economic structures within the monastery grounds provide testimony to the substantial community that once inhabited Hakobavank. Monk residences are situated in the lower-lying eastern section of the complex, and based on inscriptions and stylistic features, it is inferred that these structures were constructed during the 17th and 18th centuries.

The residential section comprises several rooms interconnected around a shared corridor. Another cluster of two-story rooms, some of which remain intact, is constructed on both the right and left sides of the main gate. Extending over 10 meters from the gate, the corridor runs beneath the enclosed structures. The living quarters were equipped with fireplaces integrated into the walls to provide heating (Fig. 10).

The refectory of the monastery, situated in the southeast corner of the wall, has collapsed, but remnants of the side walls remain standing. Interestingly, the southern entrance of the refectory served as the second, auxiliary gate of the wall.

The water source for the complex is positioned on the northwestern side of Hakobavank, nestled within a dense forest.

The monastery is adorned with numerous khachkars. According to inscriptions, the khachkar beside the northern wall of the gavit was erected in 1223, while its southern counterpart was raised a year later, in 1224. Additionally, four khachkars are incorporated into the side walls of the western window of the corridor (Fig. 11). These khachkars are not only intricately decorated but also feature lithographic elements.

The construction of Hakobavank's buildings employed the "midis" method, a technique widely used in the Middle Ages, involving rough stone and lime mortar. The architectural ornamentation follows a discreet and simple style, with more intricate processing evident in cornices, door and window cladding, fireplaces, arches, and front stages. Notably, the layout and spatial solutions of Hakobavank bear similarities to the Vorotnavank monastery in Syunik, adjacent to Artsakh. Both monasteries share an elongated east-to-west layout, with buildings positioned in the same direction and adjacent to one another (Mnatsakanyan 1960, 75). The compositional solutions of the churches, gavit, and hall also exhibit similarities. The primary distinction lies in the Church of Surb Stepanos at Vorotnavank, which features sacristies not only on the north side but also on the south side (Asratyan 1992, 84).

The condition before, during, and after the war

During the Soviet era, Hakobavank was abandoned, left to be overgrown with vegetation, and eventually fell into a state of ruin. However, in 2013, an archaeological expedition led by Gagik Sargsyan and architect Samvel Ayvazyan carried out excavation and cleaning works to restore the site. Thanks to the excavations, the monument group was saved from being engulfed by the lush vegetation that threatened the buildings. The religious and residential buildings on the eastern side, as well as the structures around the entrance, were cleared of rubble and accumulated soil. These primarily involved cleaning works, which made it possible to assess the extent of the complex. In July 2023, the cleaning works resumed in the southeast, northwest, and south parts of the monastery under the leadership of V. Safaryan. These works aimed to lay the groundwork for another project aimed at restoring and strengthening the buildings, as the monastery was in a state of emergency. On September 19, 2023, Azerbaijan took control of the monastery.

Bibliography

- Barkhutareants 1895 - Makar Bishop Barkhutareants, Artsakh, publishing house "Aror", Baku.

- CAE 5 - Corpus of Armenian Epigraphy, issue 5, Artsakh/ made by S. Barkhudaryan, Publishing House of the Academy of Sciences of Armenian Soviet Socialist Republic, Yerevan.

- Hasratyan 1992 - Hasratyan M., Artsakh School of Armenian Architecture, Publishing House of the Academy of Sciences of Armenia, Yerevan.

- Voskean 1953 - Voskean H., Artsakh monasteries, Vienna.

- Mkrtchyan 1980 - Mkrtchyan Sh., Historical and Architectural Monuments of Nagorno-Karabakh, Yerevan.

- Mkrtchyan 1980 - Mkrtchyan Sh., Historical and Architectural Monuments of Nagorno-Karabakh, Yerevan.

- Minasyan 2015 – Minasyan T., Scriptorias of Artsakh, Yerevan.

- Petrosyan, Yeranyan 2022 - Petrosyan H., Yeranyan N., Monumental culture of Artsakh, Yerevan.

The Surb Hakobavank manastery in Metsirank

Artsakh