Residential houses of Tyak village

Location

The village of Tyak is situated in the Hadrut region of the occupied Republic of Artsakh. Since 2017, it has held reserve status as it exemplifies the folk architecture of Artsakh from the 18th to 19th centuries. The construction of the village represents the entire area as a unique monument, characterizing the historical period.

Historical overview

Tyak was one of the smaller villages in the Dizak province of Artsakh, for which historical information is sparse. According to the researcher Manvel Sargsyan, the earliest recorded mention of Tyak is found in a locally authored Gospel manuscript dating back to 1563. The etymology of the village's name remains unverified; it appears in various forms in historical sources, including Tak, Tyak, Dak, and Tag (Sargsyan 1997, 5). Makar Barkhudaryants provides concise information about Tyak, noting the recent construction of Surb Mesrop Church and estimating the village's population at 175 men and 135 women (Barkhudareants 1895,67).

Architectural-compositional examination

The earliest preserved buildings and architectural elements in the village date back to the early 19th century. The settlement reached its final form in the 1920s (Sargsyan, 1997, 5-6).

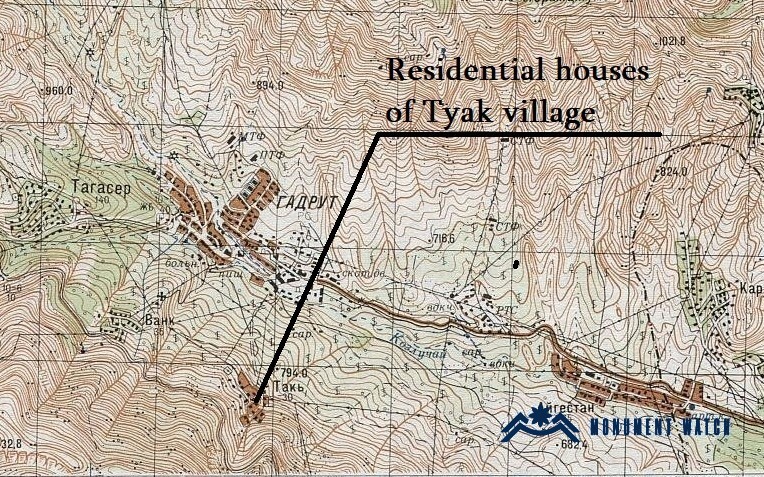

The construction of the village made optimal use of the natural terrain. Located on the northern slopes of the southern edge of the Karabakh mountain range, the village is set within a wide, semi-enclosed mountain valley. It occupies a narrow space between a steep, forested hillside and a stream flowing at the bottom of the valley (Sargsyan, 1997, 7). Many mountain villages in Artsakh share a similar location and structure (Fig. 1).

At the heart of the village is a spring situated in its eastern part, from which all the narrow streets radiate. The village is divided into three districts—Inner, Upper, and Damants-each with a distinctly different layout (Sargsyan, 1997, 11).

At the beginning of the 19th century, the most common type of dwelling was the single-section glkhatun, as is particularly evident in the dwellings of the Upper District. Many of these glkhatuns were built on slopes, were semi-subterranean, and were constructed from undressed stone and lime mortar. Internally, they featured wall niches, fireplaces, and arched entrances (Sargsyan 1997, 13-14). Starting in the 1840s, the glkhatuns (main houses) underwent reconstruction, adding new rooms adjacent to or near them. These new rooms featured windows, vaulted or flat ceilings, and contained niches and fireplaces. The dwellings also included a front hall (Figs. 2, 3). Owing to the terrain, many new dwellings were built beyond the main building, aligned along an axis and adjacent to one another. Often, such houses were constructed on the sites of former glkhatuns (Sargsyan 1997, 16-18).

New houses, often called "otagh", were frequently vaulted structures. However, some of these new types of dwellings were semi-subterranean and single-storied.

Beginning in the second half of the 19th century, a new phase of village dwelling reconstruction commenced, driven by economic development, the rise of commodity-money relations, and particularly the emergence of smaller families. Semi-subterranean glkhatuns and otaghs were no longer constructed. Above-ground one- to two-story houses with gable roofs gradually became prevalent (Fig. 4). Spacious wooden balconies appeared, featuring rooms arranged along their axis, with entrances opening onto the balcony (Fig. 5). Access to the second-floor rooms was exclusively from the balconies, which were connected to the yard by high staircases (Sargsyan 1997, 20). The economic section of the property was delineated. Small front yards began to be enclosed by fences, and arched gates made of polished stones were constructed, becoming the dominant architectural feature of the house (Figs. 6, 7). Concurrently, balconies and wooden colonnades were added to pre-existing dwellings (Fig. 8). The columnar structures of the balconies gradually acquired distinctive characteristics, transforming into unique forms with capitals and carved cornices (Sargsyan 1997, 22). Large, rectangular windows were installed in existing houses. Rooms and floors featuring innovative designs were constructed atop or adjacent to the former main dwellings. The roofs were updated to be covered with tiles.

During the late 19th and early 20th centuries, a significant transformation occurred in the village's architectural landscape: the addition of second floors to nearly all single-story houses, a practice that had not been common previously (Sargsyan 1997, 28).

Village houses were typically constructed from large and small rough stones, with all corners, doors, and windows lined with polished stone. The interiors, as well as the walls facing the balconies, were plastered and coated with lime whitewash (Sargsyan 1997, 31-32).

Thus, the houses of Tyak village allow us to trace the transformation of traditional village dwellings in Artsakh as a result of regional development. This evolution, in turn, affected the traditional way of life and introduced certain changes. The influence of urban architecture is evident.

The condition before and after the war

The village was not damaged during the Artsakh wars.

Bibliography

- Sargsyan 1997 - Sargsyan M., The historical construction of Tak village, an attempt at a comprehensive study of the transformation of the Armenian national dwelling of Artsakh, Yerevan.

- Barkhutareants 1895 - Barkhutareants M., Artsakh, Baku.

Residential houses of Tyak village

Artsakh