The Surb Stepanos Monastery: The Vachar rural town and the Surb Stepanos Monastery

Location

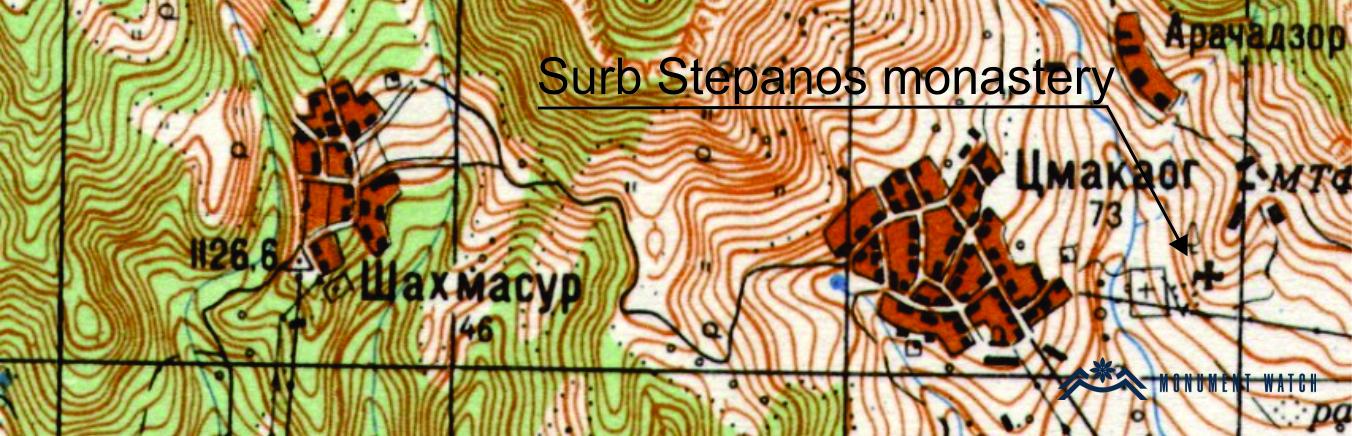

The Surb Stepanos Monastery is situated on a foothill along the left high bank of the middle valley of the Khachenaget River, a left tributary of the Khachenaget River (Fig. 1). Its precise location is approximately 500 meters south of the remnants of the village of Matak, to the southeast of the village of Tsmakahogh, within the present-day Martakert region. In the year 2017, the monastery underwent a comprehensive archaeological survey (See Surb Stepanos Monastery of Vachar: the archaeological examination).

Historical overview

There is a lack of preserved contemporary bibliographic information concerning both the village of Vachar and the monastery along with its structures. The worship practices dedicated to Saint Stepanos and the architectural designs of the associated church structures, his namesake mausoleum, and subsequently the monastery itself can only be reconstructed through a thorough examination of inscriptional, architectural, and archaeological data.

Two settlements in Artsakh bear the name Vachar. One, known as Karavachar, has its earliest written mention in a record from 1402, referring to the bishop Zakaria in the Dadi Vank province, situated in the renowned country of Tsar, specifically in the village of Karavachar (Khachikyan 1955, 24). The term "Karavachar" translates to Vachar on the promontory or rock, aligning with the geographical features of the settlement. Karavachar served as the regional center of the Nor Shahumyan district in the former Republic of Artsakh.The second settlement is Vachar in Khachen, characterized by its commercial nature, a fact substantiated not only by its name but also by the description of its ruins provided by Makar Barkhudaryants in the late 19th century. "Vachar, a dilapidated village town. On the eastern side of the village (Tsmakahogh), on the slope of the left bank of the river, one can observe substantial remnants of houses, stone remains of shops and other structures. This site corresponds to the rural town of the Jalalian princes, evident from both its name and the extant ruins" (Barkhutareants 1895, 184). The commercial character of the settlement is further underscored by its Turkish name "Bazarkend," as evident in the diary of Catholicos Yesai Hasan Jalalyan, where reference is made to "Vachar, that is, the writing of the small church of Bazar-keantu or Tsmakhogh" (Manuscript no. 7821, 20b). It is worth noting that from the late Middle Ages until the middle of the last century, the Artisan-commercial district of the village of Aparadzor, situated near Tsmakahogh, held a similar role, referred to by the people as "dukyenne" or shops. It is believed that a portion of the donation inscription left by Hasan Jalal and his wife Mamkan in the Kecharis monastery pertains to Vachar. The historical inscription, "Gave the South Vachar (1000) ducats a year," as per the reading by the lithographer Gagik Sargsyan, gains further credibility. This assumption is strengthened when considering that locals commonly refer to the Surb Stepanos Monastery as "Herava Eghtsi." An inscription from the 13th century in the Koshik Anapat begins with the statement "I Vasak bought a plot of land in Vacharategh (place of sale)...," with Sedrak Barkhudaryan suggesting that Khachen Sale is likely referred to here (CAE 5, 30, 78). If these observations hold, it becomes probable that in the 12th-13th centuries, the town served as the commercial and industrial center for the Hasan Jalalyans. Moreover, the distinctive attitude of the ruling house's representatives toward the town's sanctuaries suggests a special significance placed on these religious sites by the Hasan Jalalyan ruling family. The presence of a bishop, as indicated by a donation inscription from 1274 discovered during excavations, strongly suggests that the monastery served as a diocesan center. This role could have influenced the special attention given to the early Christian tomb, where the relics of a common Christian saint were believed to have "appeared." As a result, a new church was constructed, predating the foundation of the Surb Hovhannes Mkrtich Church of Gandzasar. Additionally, the early Christian tomb underwent reconstruction.

The structure of the monastery

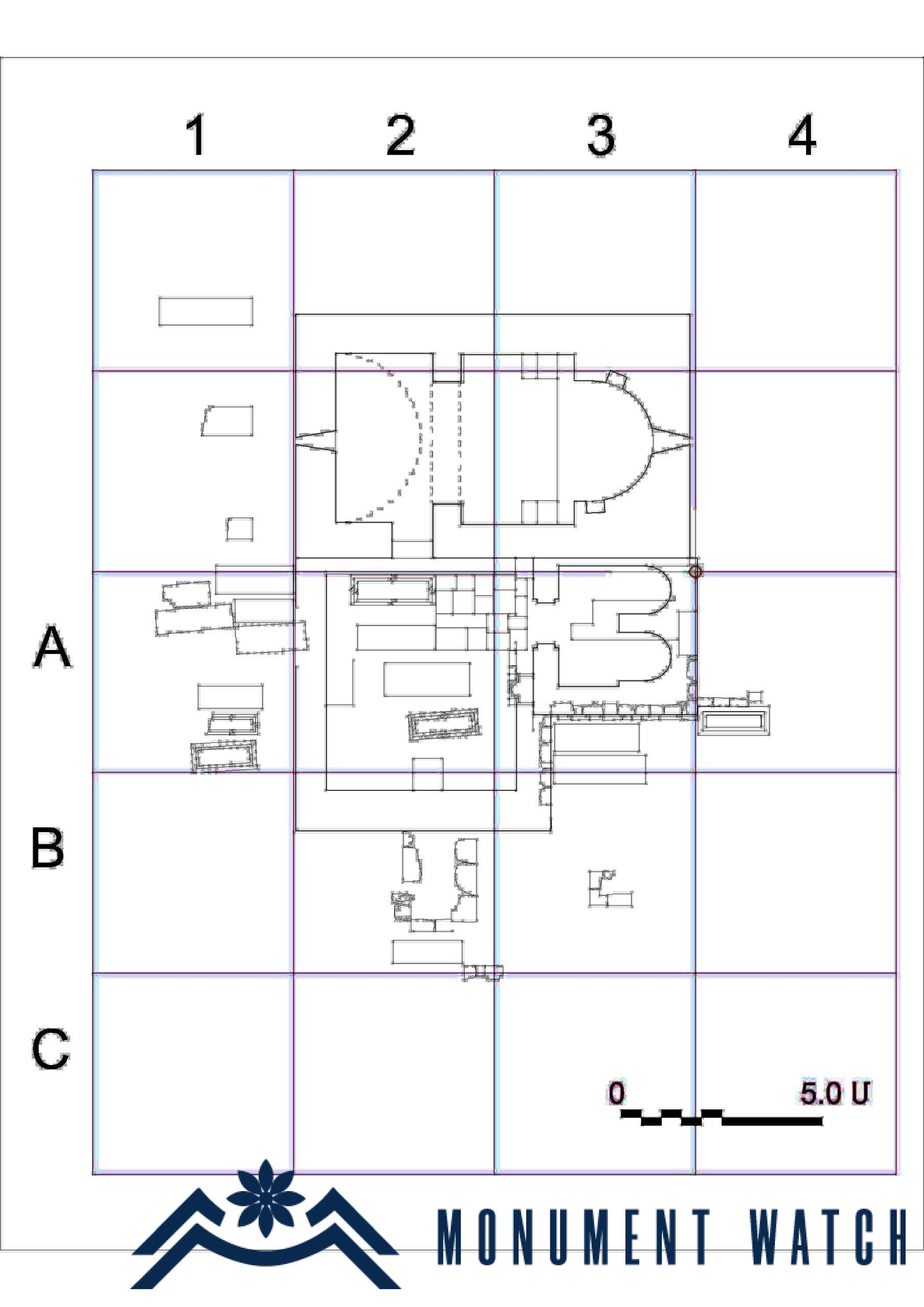

The Surb Stepanos monastic complex is composed of several key structures. This includes the single-nave Surb Stepanos hall and, as revealed by excavations, the two-story tomb chapel of Stepanos adjacent to it from the south. Additionally, there is a gavit adjacent to the chapel from the west, and numerous tombs are situated around these structures (Figs. 2, 3, 5). The remnants of a stone gate located to the north of the church and the confirmed remains of a walled khachkar are also still in existence (Fig. 4). The entire complex is encircled by ramparts fortified with towers. Inside the walls, traces of other stone-built structures are evident to the south and north of the main complex. Beyond the walls, the traces of extensive cemeteries stretch from south to north.

Bibliographic examination

The first mention of a same-named church of the Surb Stepanos Monastery of Vachar was found in the village of Aghvan in the diary of Catholicos Yesai Hasan Jalalyan, who reigned from 1701-1728. In his diary, the Catholicos copied the building inscriptions of the church and chapel, but only partially and approximately (Monuscript 7821, 9b, 20a). From the inscriptions, it is clear that Khachen prince Hasan Jalal built the church in 1229 in honor of St. Stephen's relics. His wife, Mamkan, built the chapel over the tomb in 1251. More than a century later, Hovhannes Bishop Shahkhatunyants faithfully transcribed these inscriptions from the diary of the Catholicos, maintaining their original content, and included them in his renowned book (Shahkhatunyants 1842, 377).

The first concise account of the monastery and its structures is found in the renowned "Artsakh" work authored by Bishop Makar Barkhudaryants. In this historical record, Bishop Makar describes the cemetery of the village of Vatchar, noting a relatively compact volume that houses a church constructed with cut Pumice stone. The dimensions of the church are specified as 9 meters and 8 centimeters in length, and 6 meters and 15 centimeters in width. A clandestine entrance is located behind the North sanctuary, leading to an unidentified chamber. Adjacent to the southern side of the temple, nearly touching the wall, a small two-story chapel has been erected using similar polished stones. Notably, there is also a tomb-like structure within the landscape that serves as a place of pilgrimage. The attic chapel is described as having a table along with a window and door on the west side, while the south-eastern side of the chapel has suffered damage (Barkhutareants 1895, 184-185). In his research, Barkhudaryants copied the main part of the inscriptions of the monument group and provided brief explanations (Barkhutareants 1895, 184-185). In a separate study exploring the origins of the Khaghbakyan (later known as Proshyan) princely house, particularly examining the identity of the two princes named Jajur from this dynasty, a renowned Armenologist Garegin Hovsepyan focused on the spiritual center and cemetery of the Khaghbakyans, specifically the Havaptuk monastery located on the opposite bank of Khachenaget. During his examination of an inscription from the Stepanos church, Hovsepyan highlighted the mention of the brave soldier Jajur, a prominent representative of the Khaghbakyans, whose son Grigor donated to the monastery.

In 1897, the researcher visited the ancient location and copied several other inscriptions on the stone (Hovsepyan 1928, 33).

According to certain sources, the inscriptions of Vachar were gathered in 1909 by the renowned Armenologist Hovsep Orbeli (Ulubabyan 1975, 21). However, we were unable to locate more specific information on it.

In the 1960s, the acclaimed lithographer Sedrak Barkhudaryan produced more full copies of the monument's inscriptions with remarks (CAE 5, 78-83). It is also worth noting that the western front of the chapel tomb with the inscriptions was still standing. St. and St. Stepanos Monastery is mentioned briefly (mostly from previous publications) in Shahen Mkrtchyan's book dedicated to Artsakh monuments (Mkrtchyan 1985, 31-32). It is also appropriate to bring up the pamphlet written in honor of Vachar, in which Vahram Gevorgyan enumerated and detailed the historical sites of the old settlement, such as the Surb Stepanos Monastery, as well as some recently found inscriptions and khachkars (Gevorgyan 2004).

While these descriptions touch upon Surb Stepanos' reliquary, they notably lack a specific examination and description of its semi-underground section.

Bibliography

- Barkhutareants 1895 - M. Barkhutareants, Artsakh, Aror, Baku.

- Gevorgyan 2004 - Gevorgyan V., Vachar, Yerevan.

- CAE 5 - Corpus of Armenian Epigraphy, issue 5, Artsakh/ made by S. Barkhudaryan, Publishing House of the USSR Academy of Sciences of RA, Yerevan.

- Hovsepyan 1924 - Archbishop Garegin Hovsepyan, The Khaghbakyans or Proshyans in Armenian history; Part A, Vagharshapat.

- Khachikyan 1955 - Khachikyan L., Memoirs of Armenian manuscripts of the 15th century, no. A, Publishing House of the Armenian Soviet Socialist Republic's Academy of Sciences, Yerevan.

- Manuscript no. 7821 - Matenadaran, Manuscript 7821.

- Mkrtchyan 1985 - Mkrtchyan Sh., Historical and architectural monuments of Nagorno Karabakh, Yerevan.

- Shahkhatuniants 1842 - Shahkhatuniants., Signature of the Catholic Church of Etchmiadzin and five provinces of Ayrarat, no. 2, Etchmiadzin.

- Ulubabyan 1975 - Ulubabyan B., Khachen authorities in the 10th-16th centuries, Yerevan.

The Surb Stepanos Monastery: The Vachar rural town and the Surb Stepanos Monastery

Artsakh