The Armenian Art That Azerbaijan May ‘Erase’ From Churches

On February 9, RFE / RL posted an article by Amos Chapple detailing the scandalous statement by the Azerbaijani Ministry of Culture on 3rd of February. The article presents the policy pursued by Azerbaijan towards the Armenian cultural heritage in Artsakh, the false theses proposed and propagated by Azerbaijan.

(https://www.rferl.org/a/azerbaijan-armenia-churches-inscriptions-erase/31693154.html?fbclid=IwAR1iYTdjlkVoXwjyZ7ZIYHYI9rWl6Bd90NTHh83ylP-W_S0_HXnjtA6_zyY).

Unfortunately, instead of the historical toponyms, which constitute an important component of the identity of cultural heritage, the author presented the explanations of the photos based on the administrative-territorial division of the Republic of Azerbaijan in 2020-2021. The historical name is one of the main components of the cultural identity; by giving up those names, the integrity of the cultural heritage is disturbed.

Baku announced -- then partly walked back -- steps to remove what it calls "fictitious traces” of Armenian heritage from churches now under Azerbaijani control in and around the Nagorno-Karabakh region. Archival images show what some of those inscriptions and artworks look like.

Crosses and Armenian text on the walls of the Dadivank Monastery in Azerbaijan's Kalbajar District.

The Dadivank Monastery (pictured above) is one of scores of Christian sites recaptured by Azerbaijan during the 2020 war with ethnic Armenian forces over Nagorno-Karabakh. Dadivank is currently under the control of Russian peacekeepers inside Azerbaijani territory.

A detail of Dadivank Monastery with Armenian script and carved figures.

On February 3, Azerbaijan’s Cultural Ministry caused an outcry when it announced the creation of a committee that would take steps to “remove the fictitious traces written by Armenians on Albanian religious temples” in the recaptured areas.

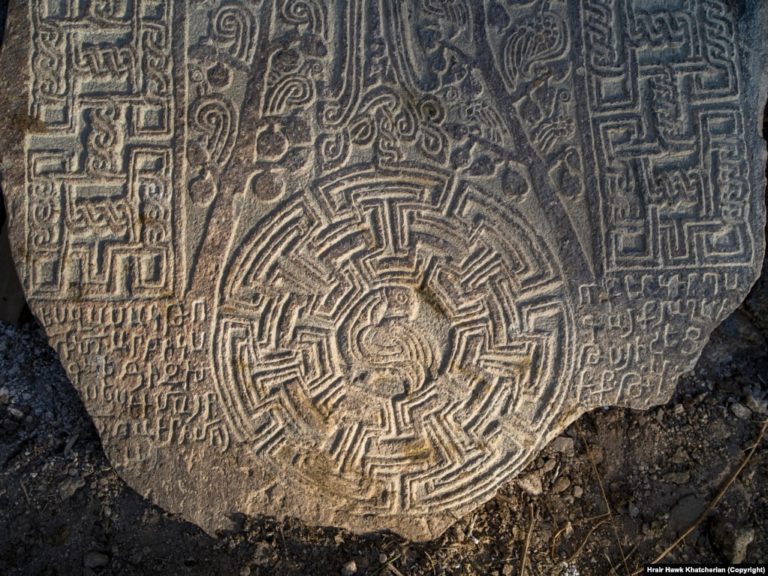

A detail of a 12th-century khachkar (cross-stone) in Handaberd, a fortress in the Kalbajar region.

In a tweet, the U.S. Commission on International Religious Freedom said it is "deeply concerned by #Azerbaijan's plans to remove Armenian Apostolic inscriptions from churches. We urge the government to preserve and protect places of worship and other religious and cultural sites."

Azerbaijani officials have repeatedly claimed ancient monuments in the Nagorno-Karabakh region are of Caucasian Albanian -- rather than Armenian -- origin and that artworks, such as the khachkar above, are “forgeries.”

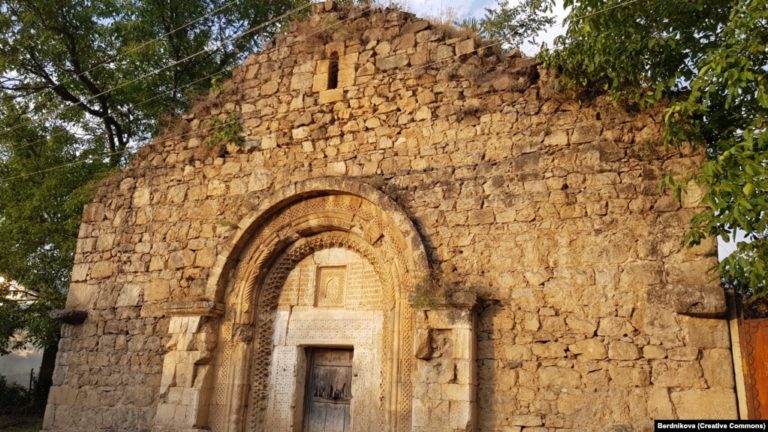

A 2018 photo of the Holy Mother of God Church in the recaptured Hadrut region. Armenian script is visible above the entrance.

When Azerbaijan’s President lham Aliyev visited the church pictured above in March 2021, he dismissed Armenian script on the entrance.

“All these inscriptions are fake,” Aliyev declared. “They were written later,” suggesting the church had Caucasian Albanian origins.

Details, including Armenian script, on a wall of the fifth-century Yeghishe Arakyal Monastery in the Tartar region of Azerbaijan.

Historians say Christian Albanian tribes did live in an area of today’s Azerbaijan. Their last king was assassinated in 822.

A small khachkar above an entranceway in the ruined Mokhrenis Church in the Hadrut region of Azerbaijan.

A khachkar in the recaptured Lachin District of Azerbaijan.

The Albanian claim has been widely panned by international scholars. Thomas de Waal, a British expert on the Caucasus, calls the Azerbaijani claims “rather bizarre” and notes the argument “has the strong political subtext” that Armenians “had no claim to [Nagorno-Karabakh].”

Bunyadov was behind a notorious article in which he claimed Armenians engineered a 1988 massacre of Armenians to vilify Azerbaijan.

A fresco inside Dadivank Monastery.

After the February 3 announcement by Azerbaijan’s culture minister that a working group had been set up to “restore Armenianized Albanian temples,” the Culture Ministry followed up with a response to the reporting of what it called “biased foreign mass media outlets.”

Armenian script at the entrance to the 13th-century St. Sargis Church in Azerbaijan’s recaptured Kalbajar District.

The February 7 statement appeared to partly walk back the earlier announcement, saying only that the working group would note any “falsifications” to monuments in recaptured territory, which would then be “presented to the international community.”

Khachkars embedded in the walls of Dadivank Monastery.

A ruling by the International Court of Justice in December 2021 on a case brought by Armenia declared that Azerbaijan must “take all necessary measures to prevent and punish acts of vandalism and desecration affecting Armenian cultural heritage” in the recaptured territories.

A cross visible on the Yerits Mankants Monastery in Azerbaijan’s Tartar District.

But there are fears -- after the erasure of Armenian heritage from the Azerbaijani exclave of Naxcivan -- that Azerbaijan will press ahead with wiping out Armenian cultural heritage in the retaken areas.

Analysts have pointed out that Baku has renewed leverage with the West due to tensions with Moscow over Ukraine.

A carved stone on the grounds of Yerits Mankants Monastery.

Amidst fears Russia could restrict gas flows to the European Union over Ukraine tensions, the bloc’s energy commissioner, Kadri Simson, visited Baku on February 4.

After the meeting, the commissioner hailed “strong bilateral” ties with the authoritarian country, while Azerbaijani President Aliyev declared a “new phase” in partnership with the EU over energy supplies.