Medieval Shushi through the Lens of Archaeological Research

The issues of Shushi's ancient history, foundation, construction, and ethnic affiliation of its different monuments have appeared on the list of "justifications" for Azerbaijan's aggressive intentions more than once. For decades, Azerbaijan's government and intelligentsia have cultivated a myth among its people, according to which Shushi began and thrived as an Azerbaijani city and the cradle of Azerbaijani culture.

Before the liberation of Shushi, Armenian researchers had limited access to the examination of written records and facts from modern times (18th-19th century). However, after the liberation, there were greater opportunities to extensively utilize various sources of archaeological, lithographic, and topographic nature. These Possibilities were, sadly, only partially utilized.

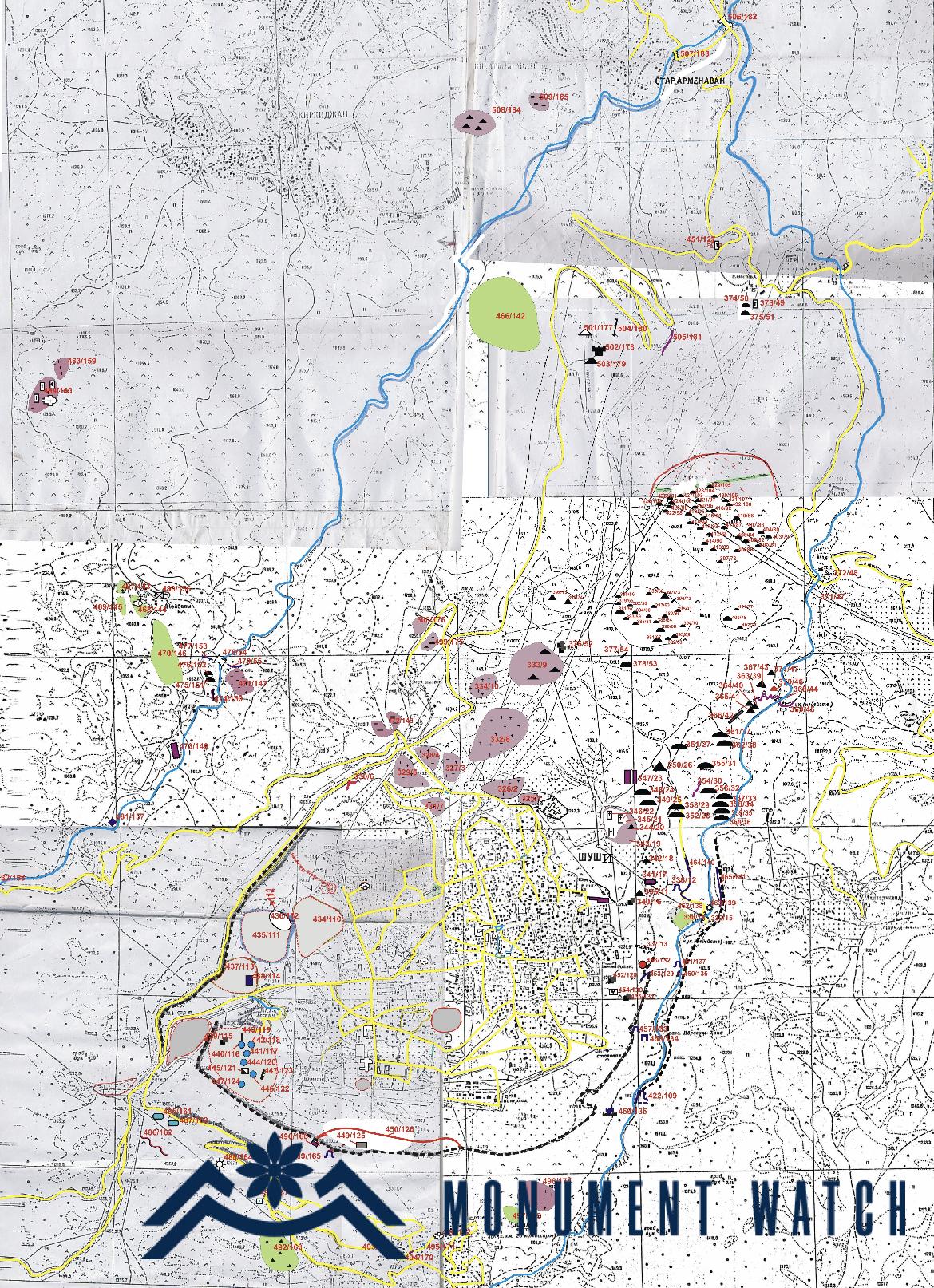

The Artsakh archaeological expedition of the RA NAS Institute of Archaeology, consisting of Hamlet Petrosyan, Vardges Safaryan, Tatiana Vardanesova, Nora Yengibaryan, and Manushak Titanyan, conducted research in Shushi and the surrounding area. In 2004-2005, they compiled a comprehensive list and map of archaeological monuments dating up to the 18th century. The list includes one Paleolithic station, one Bronze and Iron Age Cyclopean fortress, five grave fields, two ancient and two early Christian grave fields, six medieval rural settlements, and approximately four dozen khachkars.

Subsequently, an archaeological investigation of Shushi and its surrounding areas was undertaken, specifically targeting medieval monuments. The major goal was to give proof of human habitation on the Shushi plateau and the existence of Armenian civilization before the advent of Panah Khan in the mid-18th century. Excavations were conducted in the monuments listed below, yielding the following results.

Exploratory excavations of Armenian-Greek and ancient grave areas. Excavations in the old section of the Armenian-Greek cemetery near Shushi's eastern wall revealed the existence of an Armenian cemetery dating back to the 12th-13th centuries (Fig. 2). Subsequently, the khachkars from this cemetery were reused in new burials during the mid-nineteenth century. The authentication of the five khachkars from the 12th-13th centuries provides compelling evidence that the Shushi plateau was inhabited by Armenians during the prosperous era of Armenian rule in Khachen (12th-14th centuries). Additionally, the discovery of tombstones during the cleaning of a section of the Old grave area of the city is of great interest. Among them, one particular tombstone bears a date of 1771, making it the oldest Armenian inscription found within the walled territory of Shushi to date.

Discovery and excavations of Karkar fortress. The exploratory excavations of the fortress near the fortified cave known as Avan Karan in Hunot Gorge have yielded significant findings (Figs. 3, 4). Numerous artifacts from the 12th to the 14th century were discovered in the vicinity of the tandoor and within the infill during the cleaning of the upper platform (Fig. 5). The Mongolian-type arrowhead and the fragment of Chinese celadon are noteworthy as they not only demonstrate that the Hunot Gorge in the eastern part of the Shushi plateau was inhabited at the time but also that a trade route passed through here, which the Khachen princes fortified. These recent discoveries serve as valuable evidence for historians in identifying the location of the Karkar fortress, which was reconstructed at the end of the 17th century during the Armenian struggle for independence and renamed Avan, or Little Sighnagh. Karkar fortress, according to Kirakos Gandzaketsi, is one of the three fortifications associated with Hasan Jalal ("զհայրենիս- zhayrenis" meaning land inherited from father), which was initially captured by the Turks and Georgians but later returned to the prince by Batu Khan following the intervention of his son Sartakh. “He (Sartakh) took them to his father, honoring him and returning his ancestral lands of Charaberd, Akana, and Karkar, which had been previously seized by the Turks and Georgians” (Kirakos Gandzaketsi, History of Armenia, Yerevan, 1961, p. 359).

Our preliminary conclusion suggests that at the beginning of the 18th century, it was the Armenian Melik Shahnazar and the Avan Yuzbashi (“haryurapet” meaning centurion) who played a significant role in strengthening and reconstructing the ancient fortresses established by Armenian princes centuries ago, rather than the Persian and Turkish invaders.

The discovery and excavations of the Shosh village’s signagh. Through meticulous examination of the walls of Shushi and in-depth analysis of relevant professional literature, it has been determined that the ruins of one of the fortresses within the present-day area of Shushi, predating the construction of the walls by Panah in the 1750s, align precisely with the section of the wall near the Mkhitarashen gates. Large-scale excavations here show that this area within the walls was occupied at least as early as the first millennium BC. (Fig. 6).

This data holds great significance as it dispels the Azerbaijani myth claiming that the Shushi plateau was initially settled by Panah. The location of the fortress, situated directly in front of Shosh village and a mere 250 meters from the cemetery adorned with khachkars, strengthens the possibility of authenticating the renowned Shoshi stone or signagh in front of this fortress, from which some believe Shushi earned its name.

Shushi's Khachkar culture. The khachkars are also crucial in confirming the medieval Christian-Armenian image of Shushi. In addition to the khachkars recovered during excavations, khachkars were authenticated in Shushi itself and its close surroundings. I know of two khachkar fragments inside the walls of Shushi, one of which was stored in the Shushi Historical-Geological Museum and was transported here from the jail area, where it was employed as a paving stone in the yard. The second fragment is from the Mkhitarashen Gates section, which is a late 17th-century fortress, and the khachkar fragment was utilized as a building stone for the tower. Both of these khachkars are typical examples from the 12th-13th century in this region. They are set within a tabernacle featuring intricate woven lines, a central cross with tripartite bifurcations, and depictions of bunches of grapes descending from the upper corners of the tabernacle towards the cross.

About two dozen khachkars dating from the 10th-14th centuries have been confirmed near Shushi, which includes the Karin Tak and Karkar River interfluve. They are the most common examples, with woven ornamented belts, crosses inserted in the niche, sculptures representing the deceased and their relatives, armed warriors, hunting scenes, and so on (Figs. 7, 8). Some of them have Armenian inscriptions on them. On the cornice of the khachkar, for example, where the warrior and his brother are positioned, we can read: "In the year of 1208/ I Avanes raised this cross."

The discovery of the fortress and archaeological remains in the Shushi plateau and its surrounding gorges sheds light on the 12th-14th century fortress and archaeological culture in the Hunot Gorge. This gorge served as a branch of the Silk Road, connecting Artsakh to Syunik. Additionally, the area is home to 17th-18th century fortresses, castles, bridges, mills, cemeteries, and rural settlements. Khachkars and tombstones are scattered throughout the plateau. These findings provide evidence that the Shushi plateau and its surroundings were inhabited and shaped by Armenian civilization and culture for centuries, long before Panah constructed fortifications in the mid-18th century.

Bibliography

- Petrosyan H., Safaryan V., Medieval Shushi according to archaeological excavations, Shushi: Cradle of Armenian Civilization, Proceedings of the conference dedicated to the 15th anniversary of the liberation of Shushi, Yerevan, 2007, pp. 268–272.

- Petrosyan, Khachkar culture of Shushi and its surroundings // Armenian Studies (collection of articles), Stepanakert, Artsakh State University, 2013, p. 23–34.

- Petrosyan G., Safaryan V., Yengibaryan N., Titanyan M. Archaeological evidence of the existence of ancient settlements on the territory of Shushi // Phenomenon of Shushi. Historical and political research, Workbooks, 1-2 (25-26), Yerevan, 2013, p. 30-39.