The Artsakh State Historical Museum of Local Lore

History

The Artsakh State Historical Museum of Local Lore, located at 4 Sasuntsi David Street in Stepanakert, the capital of the Republic of Artsakh (Fig. 1), was one of the inaugural museums established in the region during the Soviet era. It curated and exhibited the archaeological and ethnographic heritage of Artsakh in line with the principles governing Soviet-era “local history” museums.

The museum was established in 1939. In 1938, Y. Hummel, director of the Khanlar Museum of local lore, was dispatched to the southern part of Stepanakert, specifically to the village of Krkzhan (now within the boundaries of the Armenakavan district in Stepanakert), to investigate an accidentally discovered treasure. Upon his arrival, Hummel initiated an excavation project in the village. The Stepanakert Museum of History and Geology was established in 1939 based on the materials excavated from tombs N102 and N103 by Hummel.

Stepanakert has been under Azerbaijani occupation since September 2023.

The collection

Despite operating under the cultural policy of Soviet Azerbaijan, the museum managed to amass a significant collection of archaeological and ethnographic artifacts from the region, even during the Soviet era. As a result, it emerged as one of the most important cultural institutions in the region. In a statement made between 1988 and 1991, V. Safaryan, the museum’s director at the time, noted that the museum entered a more dynamic phase of activity during the late Soviet period in the 1980s. The museum's activity significantly declined between 1988 and 1994 due to the Karabakh movement and the Armenian struggle for liberation. However, under relatively stable conditions, the Artsakh State Historical Museum of Local Lore resumed its operations, actively collecting and displaying museum artifacts. Unfortunately, during the Soviet era, many of the most important archaeological finds unearthed in Artsakh were transferred to Baku. Notably, collections from the Khojalu burial ground and the Azokh cave excavations were among those transferred.

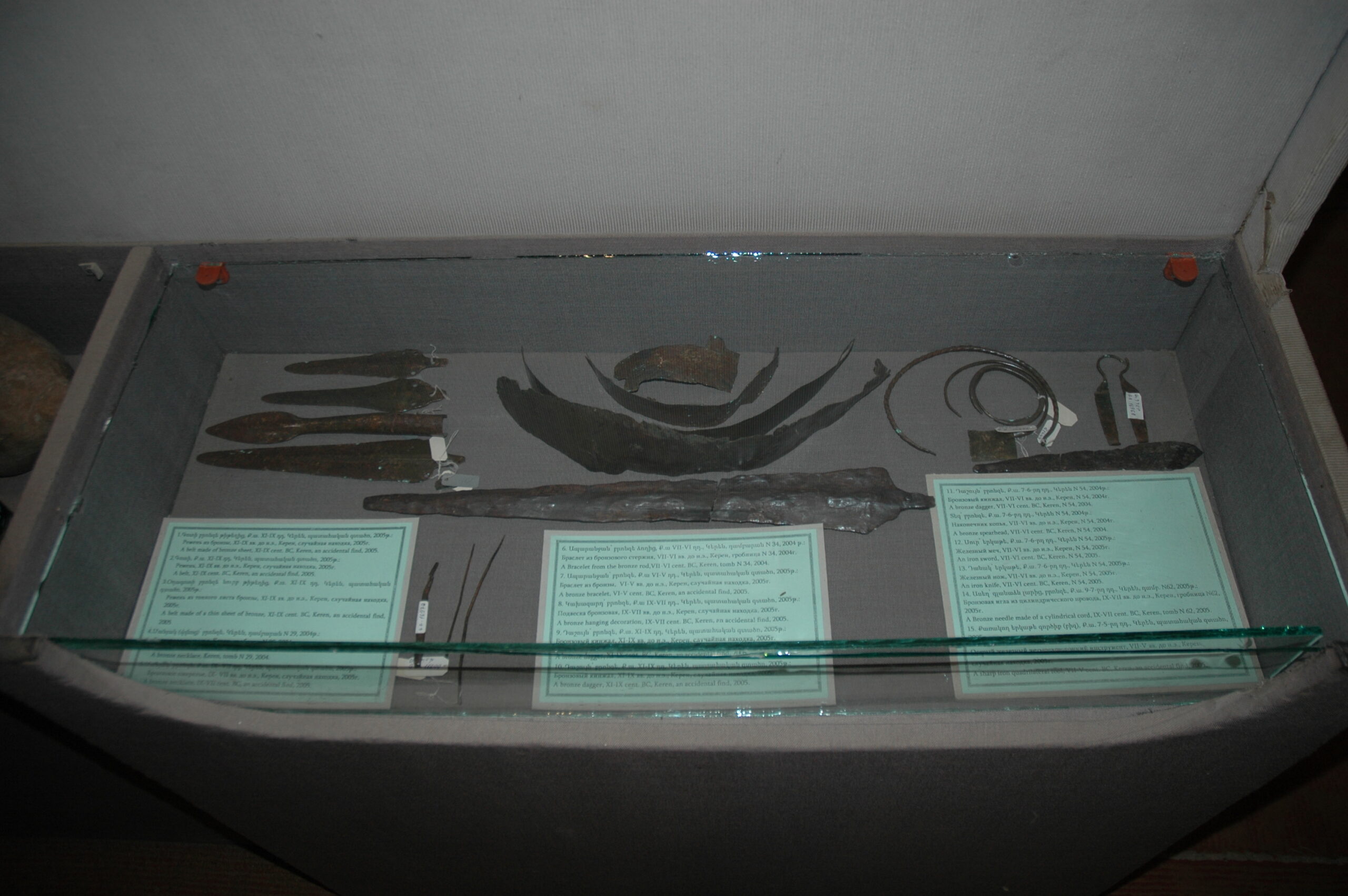

During the period of independence, around 50,000 items were added to the collections and exhibitions of the Artsakh State Historical Museum of Local Lore . In the 2000s, the museum's collection grew significantly, thanks to numerous archaeological discoveries from sites such as Shushi, Keren, Handaberd, and other locations, as well as the acquisition of an extensive collection of ethnographic materials.

Following the declaration of independence of the Artsakh Republic, the reopening of the museum was greatly facilitated by the establishment of direct links with Armenia. These links provided the museum with substantial support in methodology and professional expertise. As a result, the registers from previous years were updated and completed, the exhibits underwent rigorous scientific processing, and proper documentation, including the preparation of object records, was finalized.

The permanent exhibition was also subject to modification as part of the overall restructuring. Following the onset of the movement in 1988, the communist propaganda posters in the museum's lobby were removed and replaced with a concise historical overview of Artsakh. Additionally, the final hall was altered to include a dedicated section on the Artsakh Freedom struggle .

The new exhibition concept was reviewed and approved during a joint extended session of the Collegium of the Ministry of Culture, Science, and Sports of the Nagorno-Karabakh Republic, along with the Museum’s Scientific Council, on December 24, 1993 (Mkrtchyan 2001, 373-382).

The exhibition was organized as follows: it began with illustrative depictions capturing the essence of Artsakh, followed by a presentation of the archaeological section (Figs. 2-8).

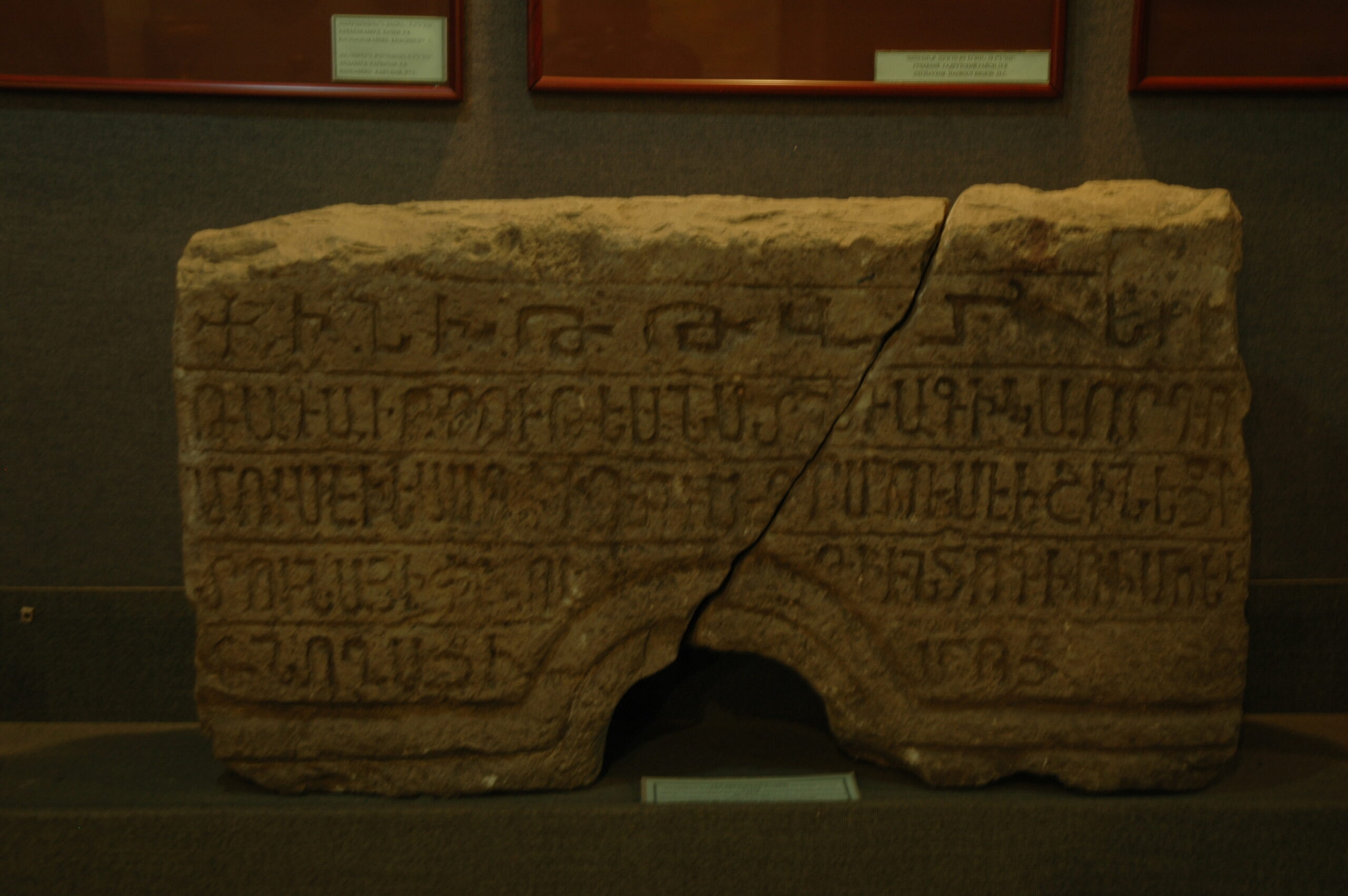

The medieval section of the museum opened with a photograph of Amaras and a map highlighting the medieval monuments of Artsakh. The medieval section was also filled with photos and informational panels about the fortresses and strongholds of Artsakh.

The theme of the third hall focused on Artsakh before the Arab invasion. It presented an early medieval bibliography, literature, and the art of writing manuscripts (featuring figures such as Movses Kalanaktuatsi and Davtak Kertogh), the liberation of Artsakh from Arab rule, the establishment of the Armenian Bagratid Kingdom, the cultural renaissance of this period, and the rise of the Principality of Khachen.

The next hall showcased the history of the Khamsa Melikdoms.

On the second floor of the museum, the history of Artsakh during the Soviet and post-Soviet periods, including the national liberation struggle of Karabakh from 1990 to 1994, was presented.

The largest stone monuments in the collection were displayed in the museum's courtyard. Among these were two examples of anthropomorphic sculptures from the 8th to 6th centuries BC, khachkars from various periods, and other significant large exhibits (Figs. 9-12).

In addition to the museum's primary exhibition, the entrance door itself was a significant artifact (Figs. 13, 14). Crafted by the Artsakh artisan Robert Askarian between 1983 and 1985, the door was fashioned from locally sourced Artsakh walnut. Each of the two shutters was intricately subdivided into three sections, framed by detailed carvings. These carvings featured symbolic representations of traditional Armenian architecture, family life, and cultural heritage, reflecting the craftsmanship and cultural values of the region. The first and second images are divided by an inscription that reads: "Gifts of the Karabakh land" and "Gifts of the warmth of hearths" (by Gurgen Gabrielyan). As noted by the sculptor, in 1985, the local communist authorities disapproved of this initiative and threatened to remove the door entirely unless the Armenian inscriptions were replaced with texts in Azerbaijani and Russian. However, the Karabakh movement and the eventual independence of Artsakh likely prevented this from taking place.

The activity of the museum before the war

Much like during the years of independence, the museum continued to engage in active exhibition and educational activities following the 44-day war. Over the years, its programs and collections were documented in catalogs (Balayan 2011; Balayan, Poghosyan 2020) and informative brochures. The museum hosted various educational programs for schoolchildren and students, making it a favored destination for tourists visiting Artsakh.

The museum remained active even during the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic and the period following the 44-day war (Figs. 15-16). In the aftermath of the war, the museum hosted various temporary exhibitions, lectures, and other educational programs. Notably, soldiers from the Russian peacekeeping forces also participated in these events (Figs. 17-18).

The condition after the war

During the forced deportation of Armenians from Artsakh in September 2023, a portion of the museum's exhibition collection was successfully relocated to a safe place. However, the majority of the exhibition materials and collections remained in the museum. The current condition of both the museum and its collection remains unknown.

The museum and international law regulations

As with any cultural property, the international legal-legislative basis for the protection of museums and collections is the 1954 Hague Convention for the Protection of Cultural Property in the Event of Armed Conflict and its two protocols (1954 and 1999). According to Article 4 of the 1954 Hague Convention, any acts of vandalism, theft, robbery, misappropriation, hostilities, and reprisals against cultural heritage are prohibited. Furthermore, according to the first Hague Protocol of 1954, it is forbidden to destroy cultural or spiritual values in occupied territories. The Second Hague Protocol of 1999 reaffirms this requirement and classifies such acts as international crimes under Article 15. The destruction of cultural values is also prohibited by four international conventions and protocols on the protection of war victims, the laws and customs of war established in the Geneva Conventions of August 12, 1949, as well as relevant UN resolutions and human rights treaties.

Bibliography

- Balayan 2011 - Balayan M., the fabric collection of the Artsakh State Historical Museum of Local Lore , Yerevan, Zangak.

- Balayan, Poghosyan 2020 - Balayan M., Poghosyan A., The collection of silver jewelry of the Artsakh State Historical Museum of Local Lore , Yerevan, Zangak.

- Mkrtchyan 2001 - Mkrtchyan Sh., Artsakh Notes, “Noyan Tapan”, Yerevan.