The Surb Astvatsatsin Church of Voskepar: Historical and Architectural Study

Location

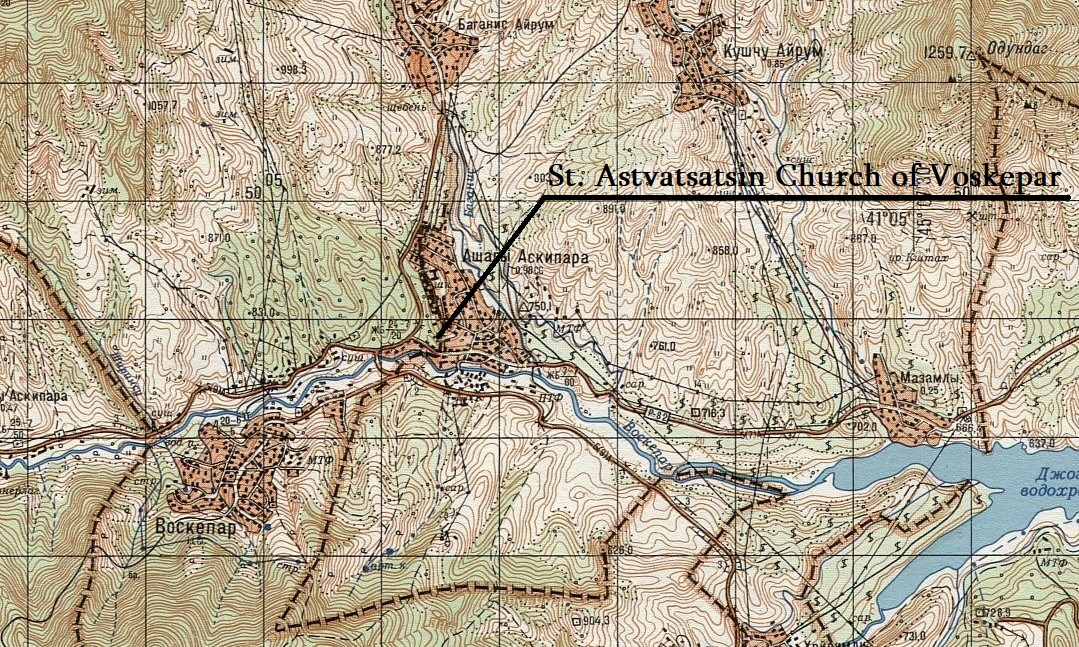

The Voskepar village is located in the northeastern part of Tavush Region, Republic of Armenia, adjacent to the Armenian-Azerbaijani contact line, on the north-facing slope of the right bank of the Voskepar River. The village has also been referred to as Voskepat and Voskeparisp (Hakobyan, Melik-Bakhshyan, Barseghyan 1998, 175). The village is rich in various monuments from both the Christian and pre-Christian periods. Among them, the Surb Astvatsatsin Church of Voskepar is notable. It is located 400 meters northeast of the village on the south-facing slope of the left bank of the Voskepar River (Fig. 1).

Historical Overview

The Surb Astvatsatsin Church of Voskepar is not mentioned in historical sources. The first written record of the structure appears in the work of folklorist S. Kamalyan, who, while visiting the site in 1884, noted:

"On the eastern side of the old village, on the edge of the gorge, is built this monastery, a cross-shaped church, both internally and externally made of finely polished stone; it has a newly built katoghike…" (Karapetyan 2013, 14).

The compositional, structural, and artistic features of the church have been studied by Stepan Ter-Avetisyan (Ter-Avetisyan 1937, 505-511), Anatoly Yakobson (Yakobson 1948, 29-35), Gevorg Shakhkyan (Shakhkyan 1986, 167-168), Paolo Cuneo (Cuneo 1988, 319), Varazdat Harutyunyan (Harutyunyan 1992, 146-147), Samvel Mnatsakanyan (Mnatsakanyan 2004, 55-58), Patrick Donabédian (Donabédian 2008, 162), Murad Hasratyan (Hasratyan 2010, 25), and Samvel Karapetyan (Karapetyan 2013, 10-16). Anahit Ghazaryan has also adpolished issues of the church’s dating, preservation, restoration, composition, and decoration (Ghazaryan 2012, 302-316).

Most researchers date Voskepar Church to the second half of the 7th century based on its compositional, structural, and artistic characteristics. However, Murad Hasratyan believes that the architectural features and decoration of Voskepar are typical of the first half of the 7th century (Hasratyan 2010, 25). It should also be noted that some authors, without sufficient grounds, attribute the church’s construction to the 9th-10th centuries (Chubinashvili 1967, 151; Thierry 1978, 20-21).

Architectural-compositional examination

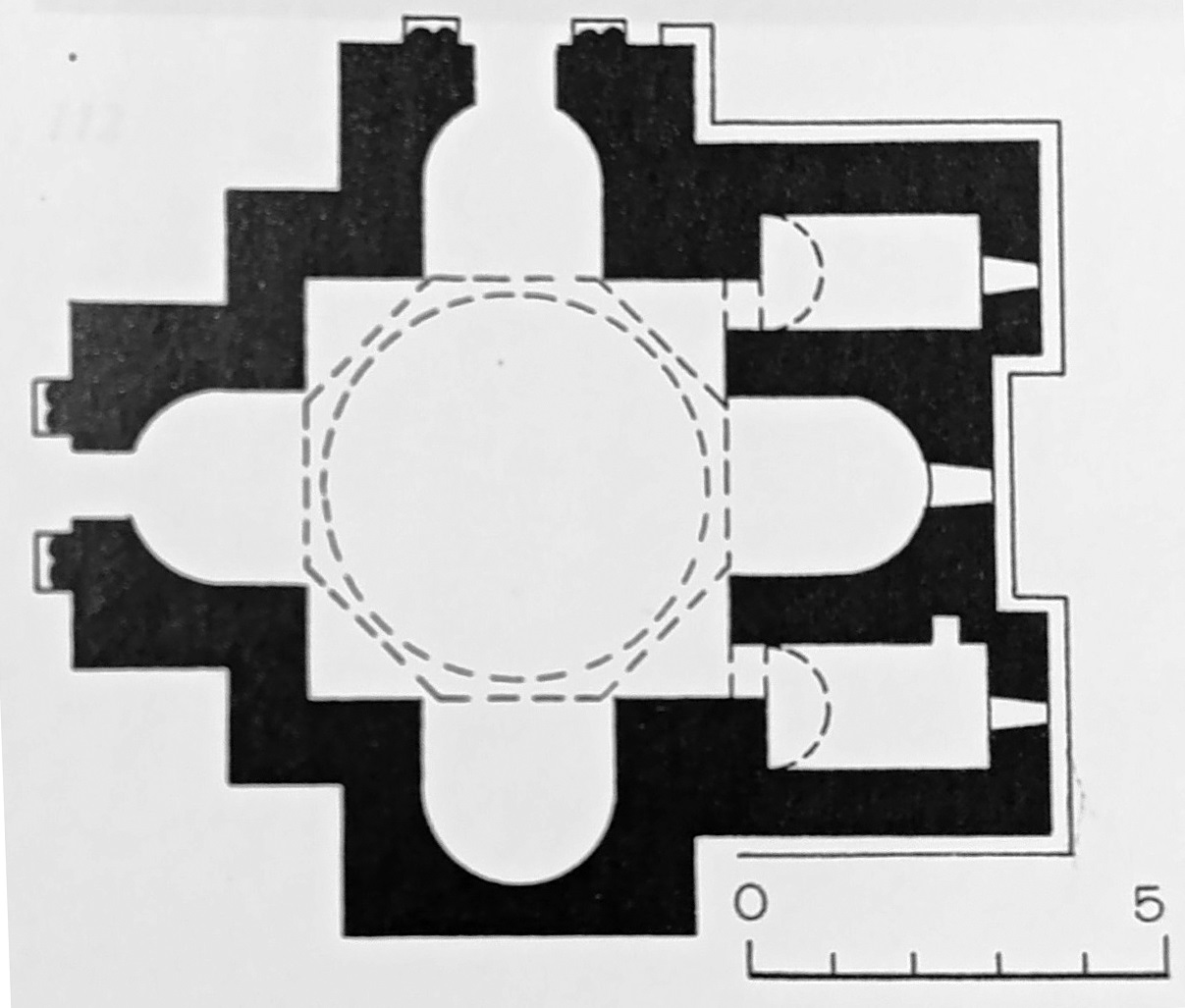

The Voskepar Church belongs to the compositional subtype of small cross-domed churches with four sacristies, widely seen in the early medieval period. The monument is a small-scale example of the Mastara-type churches (external dimensions: 11.2 x 10.8 meters; prayer hall dimensions: 5.37 x 5.74, fig. 2).

From the approximately square prayer hall, deep, slightly horseshoe-shaped sacristies extend in the cardinal directions. The center of curvature of these sacristies is set back 0.65 meters from the front line. Externally, the sacristies are rectangular, unlike other examples of this type (Mastara, Harich, Artik, Kars), where they are polygonal.

On either side of the high altar are rectangular sacristies extending east-west. Their placement on the eastern façade creates protrusions. The sacristies are single-story, covered with barrel vaults, and lit by windows in their eastern walls. In their external volumes, they are significantly lower than the high altar and slightly project from the eastern façade, standing out from the main mass (Fig. 3).

The church has two grand entrances, located on the western and southern façades, crowned with gable pediments resting on pairs of semi-columns. The entrances are identical in size and design. Fish motifs are carved on the bases of the pilasters of the western portal (Kazaryan 2012, 304). Cross-shaped reliefs are carved on the lintels of the doors (Hasratyan 2010, 25). The cornice is adorned with repeating geometric ornaments(Fig. 4).

The compositional solutions of the high altar and the bema are particularly noteworthy. The low bema typical of early medieval churches (only 0.3 meters high) extends across the entire width of the structure, reaching the sacristy entrances. Around the perimeter of the sacristy is a 0.24-meter-wide and 0.52-meter-high bench designed for senior clergy. The bench’s side elements are made of single stones and form a direct continuation of the wall masonry (Fig. 5).

Windows in the sacristies (except the northern one) and four windows in the drum provide light to the interior. The windows feature simple early medieval caps. They are convex, and two of them have lilies carved into them (Fig. 6).

The facets of the drum are articulated by a decorative arcade rising from pairs of half-columns positioned at the corners. The transition from the square base beneath the dome to the dome itself is achieved through scrunches (Fig. 7), placed on the upper surfaces of the drum’s faces. The church’s drum is crowned with a conical (or pyramidal) roof set on an octagonal base (Fig. 8).

The monument’s external volumetric composition clearly reflects its internal structure. The main volume of the church corresponds to the space beneath the dome, to which the rectangular cross-arms with double-pitched roofs—enclosing the apses—are attached. Such a composition is found in small-scale "free-cross" type churches of the early medieval period (e.g., Surb Astvatsatsin of Karmravor, Vankasar Church, etc., Kirakosyan 2013, 122). On the eastern side, the structure is joined by the volumes of the sacristies with pitched roofs. To create unity between these volumes and the main mass, it is likely that two sets of steps run along the eastern projections of the sacristies and the eastern apse of the church. On the other sides, the walls rest on a one-step foundation. The church’s octagonal drum is decorated with a blind arcade. These arcades are heavily weathered. Nevertheless, the preserved elements (the window arches, the inclined surfaces of the cornices, and the portal treatments) testify to the church’s early medieval origin and the decorative elements characteristic of that era. Above the western window of the church, there is a protruding horizontal upper cornice, about whose purpose researchers have not expressed a definite opinion (Armenian Architecture 2004, 56).

The church is constructed of fairly large, finely polished yellowish-brown and pink felsitic tuff stones. Horizontal clamp ends and mason’s marks are visible on the wall masonry (Armenian Architecture 2004, 55). The walls were originally plastered on the inside.

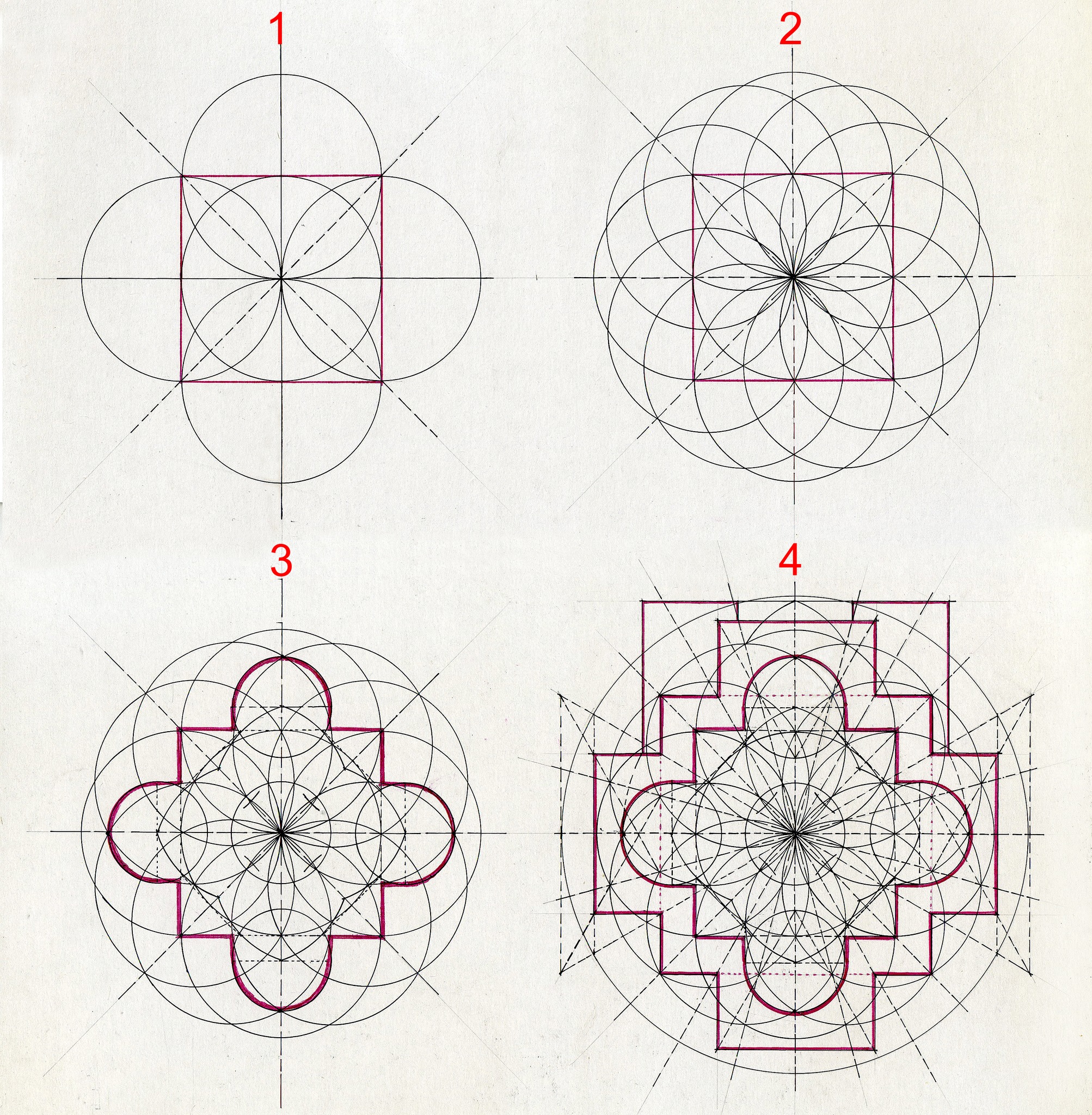

Owing to the perfection of its plan, volumetric-spatial solutions, and proportions, the church rightfully holds an important place among early medieval monuments of its kind. The architectural concept is so refined that the church’s plan and façade drawings can be derived through the simplest geometric constructions, using the internal span of the dome as a starting point (Fig. 9).

This type of monument-with supporting niches on the main axes, to which Voskepar Church belongs—played an important role in the formation of Armenian centrally domed compositions. They represent a transitional form between the smaller, centrally domed, quatrefoil type and the more complex, centrally planned compositions based on a cross-shaped layout.

Restoration

The church has remained in a relatively well-preserved state, though its upper sections, particularly the roofs, have sustained significant damage (Fig. 10). Its current appearance is the result of an extensive restoration undertaken between 1975 and 1977, based on the architectural design of Hrachya Gasparyan. This restoration drew upon a detailed analysis of fragments uncovered during excavations and cleaning efforts (Tamanian 1981, 24-26).

Despite these efforts, the church roofs now require further repair. During a routine inspection, specialists from the RA Ministry of Education, Science, Culture, and Sports’ "Preservation Service" SNCO identified considerable erosion and damage to the roof coverings, creating conditions conducive to moisture infiltration. To mitigate further deterioration, the Preservation Service has deemed roof repairs a priority (https://hushardzan.am/archives/30351).

Bibliography

- Tamanian 1981 - Tamanian Yu., The Restoration of the Stone Chronicle: Archival and Factual Materials, ed. by E. Shahnazaryan, Association for the Preservation of Historical Monuments of Armenia, Yerevan.

- Karapetyan 2013 - Karapetyan S., The Historical Monuments of Voskepar, Yerevan, archived electronic version, 2021-08-31.

- Kirakosyan 2013 - Kirakosyan L., The Architecture of the Vankasar Church and Azerbaijani "Restoration", Historical-Philological Journal, No. 1, pp. 120–133.

- Hakobyan, Melik-Bakhshyan, Barseghyan 1998 - Hakobyan T., Melik-Bakhshyan St., Barseghyan H., Dictionary of Toponyms of Armenia and Adjacent Regions, Yerevan University Press, Yerevan.

- Hasratyan 2010 - Hasratyan M., Armenian Early Christian Architecture, Moscow.

- Harutyunyan 1992 - Harutyunyan V., History of Armenian Architecture, Yerevan.

- Mnatsakanyan 2004 - Mnatsakanyan S., History of Armenian Architecture, Vol. 3, Yerevan.

- Kazaryan 2012 - Kazaryan A., Church Architecture of the Transcaucasian Countries in the 7th Century: Formation and Development of Tradition, Vol. 3, Moscow.

- Ter-Avetisyan 1937 - Ter-Avetisyan S., Notes on Voskepar and Kirants, Materials on the History of Georgia and the Caucasus, Vol. 7, Tbilisi.

- Chubinashvili 1967 - Chubinashvili G., Research on Armenian Architecture, Institute of Georgian Art, Tbilisi.

- Yakobson 1950 - Yakobson A., From the History of Armenian Medieval Architecture: The Church in Voskepar, Brief Reports of the Institute of the History of Material Culture Named After N. Marr, Moscow-Leningrad.

- Shakhkyan 1986 - Shakhkyan G., History of Armenian Art, Yerevan.

- Cuneo 1988 - Cuneo P., Architettura Armena, Vol. 1, Rome.

- Donabédian 2008 - Donabédian P., The Golden Age of Armenian Architecture (7th Century), Marseille.

- Thierry 1978 - Thierry J., The Cathedral of the Holy Apostles of Kars (930-943), Paris.

- Voskepar Church 2024 - Voskepar Surb Astvatsatsin Church: Before and After Restoration, https://hushardzan.am/archives/30351, accessed May 23, 2024, 07:49.