Charektar Monastery: archaeological research

During the Soviet era, Charektar village underwent depopulation and was subsequently occupied by Azerbaijanis, resulting in substantial losses for the local monastery. Throughout this period, the monastery endured extensive damage and alterations, with its structures repurposed into cattle sheds. A significant number of khachkars were shattered, tombstones were displaced, and some were repurposed as building materials for the construction of economically significant structures.

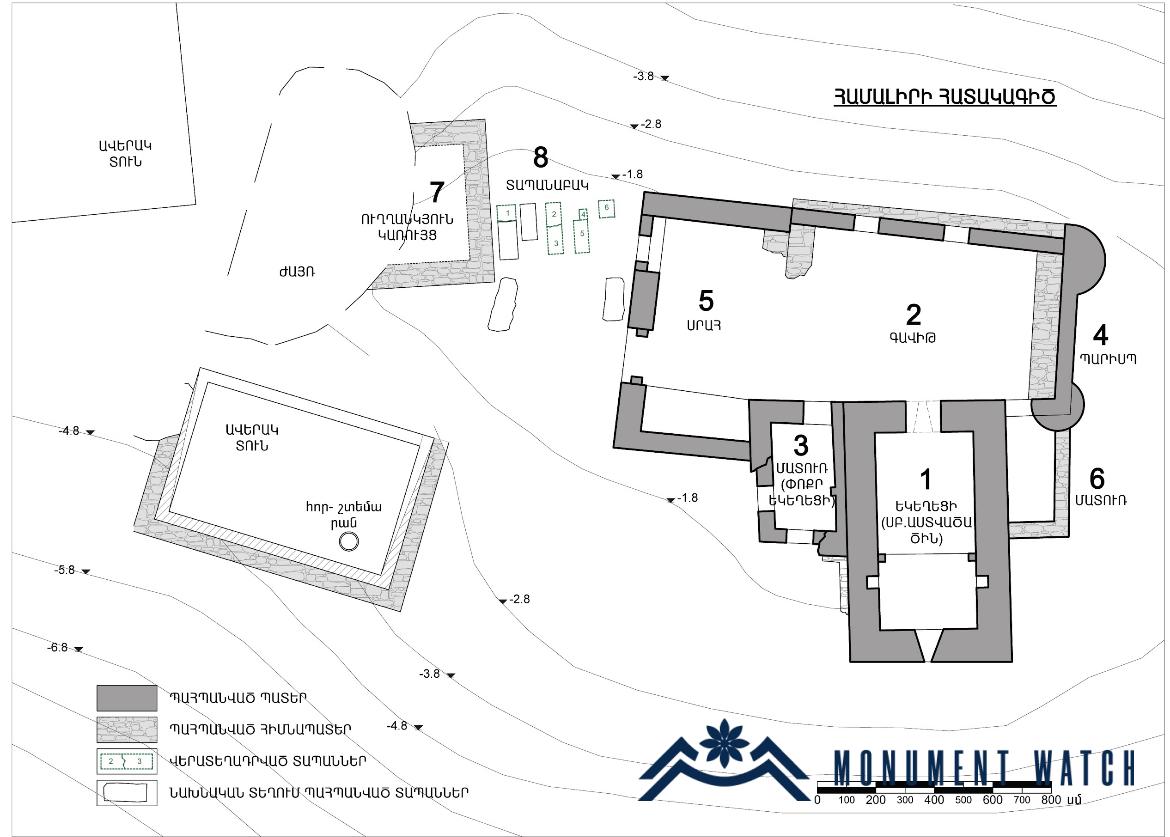

During the Republic of Artsakh's tenure, the government outlined plans for the reconstruction of the monastery, but only the initial research phase was executed. Commencing with the excavations in 2009, the complex's grounds were cleared, the built-up area boundaries were adjusted, the functional significance of the structures was delineated, and the chronological evolution of the monastery's construction and reconstruction was elucidated (Fig. 1).

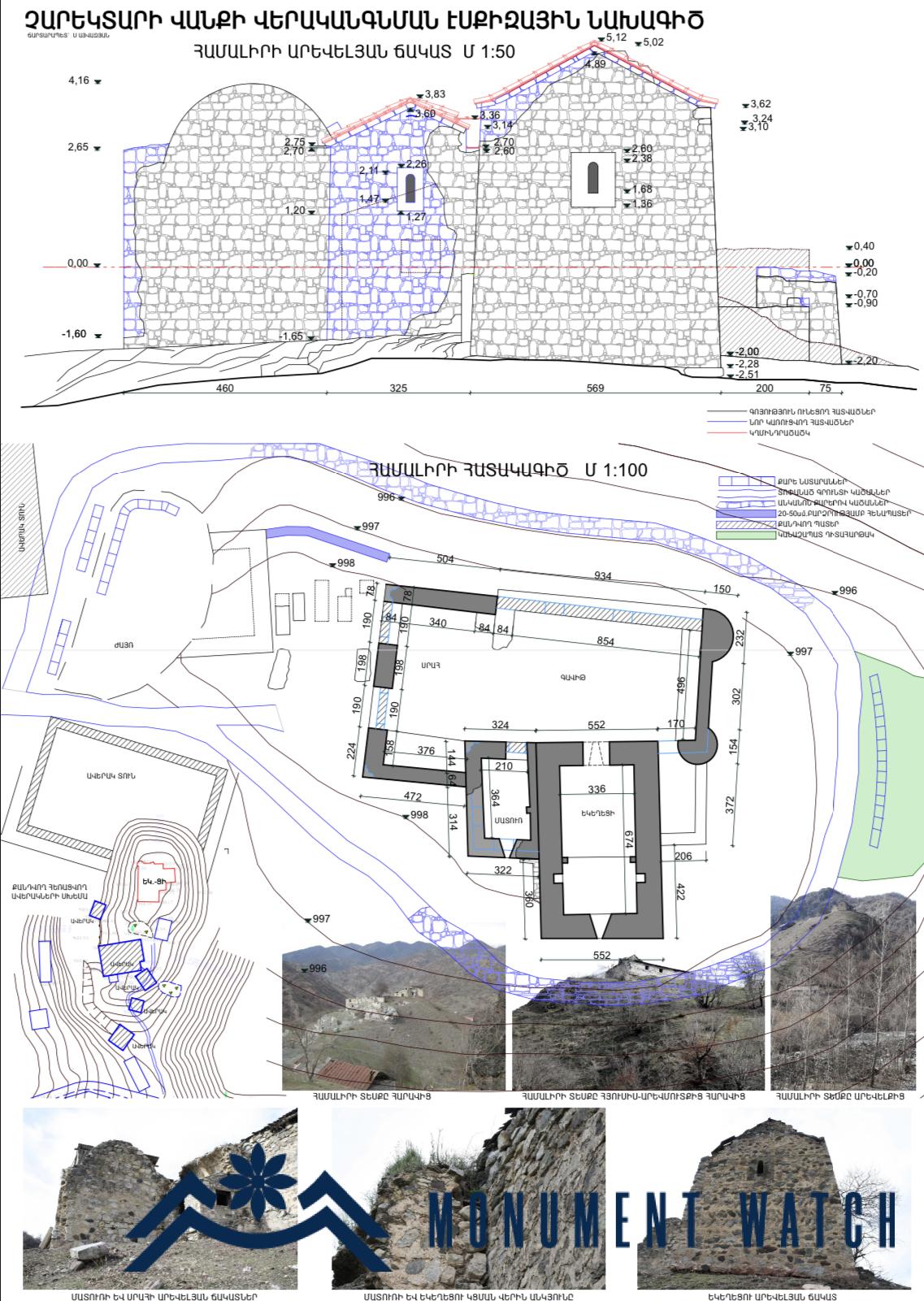

Thanks to the combination of excavations architectural research works, and bibliographic information, it became possible to make some summaries (Ayvazyan, Sargsyan 2011, 56). The fragment of a khachkar found in 1002 indicates that the territory of the monastery functioned as a place of worship from that time on (Fig. 2). Excavations on the northern side of the monastery complex unveiled only a section of walls fortified with two towers. Absent were walls on the other sides, a circumstance suggesting that the monastery's grounds were not enclosed along the entire perimeter—a departure from the typical layout of most medieval monastic complexes. Tombstones and khachkars were discovered incorporated into the walls of Muslim residential houses, a finding resulting from archaeological excavations (Ayvazyan, Sargsyan 2011, 52-55).

The earliest extant structure is the monastery church, believed to have been constructed in the 12th-13th centuries. Subsequently, a gavit was added to its western side.

In the subsequent phase of development, the complex saw the construction of a small church, seamlessly affixed to the western section of the southern wall of the main monastery church. Meticulous site examinations brought to light that during the construction of the small church, the gavit had already incurred significant damage. The lower segment of the west wall of the addition integrated with the gavit wall, whereas the upper part was erected as an autonomous wall. This distinction arose due to the absence of the gavit wall beyond that particular level.

During the third phase of construction, likely in the 13th and 14th centuries, the northern wall, complete with its towers, was annexed to the northern side of the gavit.

Following this addition, the vaulted hall was constructed. Positioned adjacent to the southern facade of the gavit, the hall unfortunately met its demise along with the gavit. This occurred when the Muslim population repurposed the space, transforming it into a barn and implementing various modifications. Notably, the southern wall of the colonnade featured two openings—one for a door and another for a window—both adorned with arrow-shaped arches (Fig. 3). Researchers have discerned a marked distinction in the mortar composition of the walls in this particular structure compared to others. The mortar, characterized by its yellowish hue and a mixture of clay, exhibits a relatively lower strength (Ayvazyan, Sargsyan 2011, 57). This distinctive feature, coupled with the construction method employed for the colonnade, leads to the conclusion that its construction can be attributed to a period after the 17th century.

The final stage of the monastery's reconstruction dates back to the early 20th century. During this period, the walls of the gavit and portico were utilized in the construction of a cattle shed. It featured thinner walls and was supported by wooden columns within its structure (Fig. 4).

The progress of excavations has documented reconstructions of the monastery's church, evident in the visible traces on its facade. Originally, the church featured a vaulted and tiled gable roof. Subsequently, modifications were made, replacing the nave with a wooden covering, and the interior walls were plastered. Notably, the stucco on these walls showcases an intricately carved decorative belt adorned with rosettes, painted in vibrant red and blue hues, running along the inner perimeter of the building (Fig. 5).

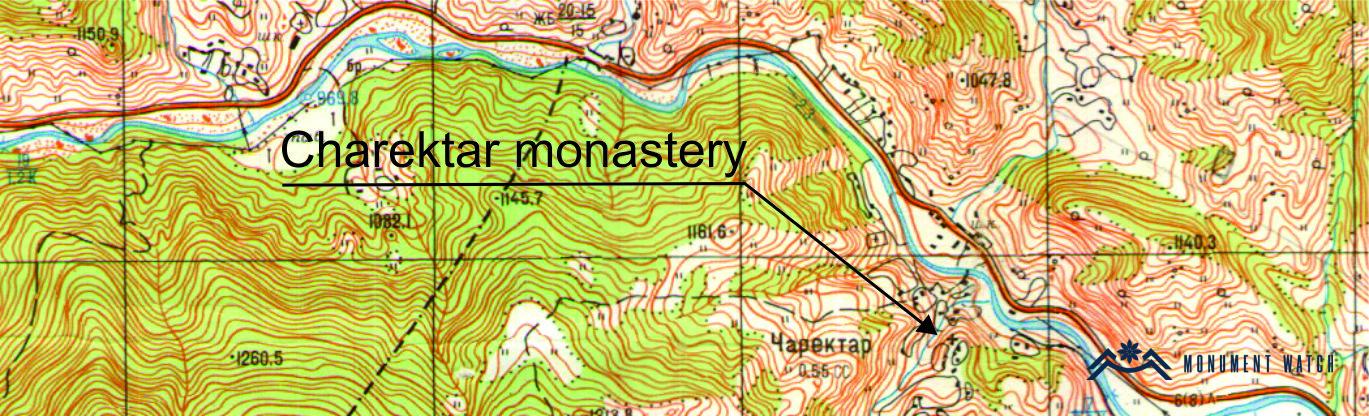

The examination of excavation data has facilitated the presentation of comprehensive restoration and reinforcement projects for both the Charektar Monastery church and chapel, along with partial restoration efforts for other structures. As outlined in the project, the restoration plan included rebuilding the upper part of the walls of the chapel and the church, extending to approximately 1.0 meters in height. Additionally, the roofs of these structures are slated for coverage with tiles as part of the restoration process. The surviving sections of the remaining structures required reconstruction and stabilization up to a designated height. The monastery's surroundings were envisaged for improvement through the implementation of irregular stone and rammed soil pathways. Furthermore, the project included the construction of retaining walls up to 50 cm in height, the installation of benches, and the establishment of a verdant viewing platform (Fig. 6). Unfortunately, the restoration plan was never realized. Moreover, due to a large-scale armed aggression carried out by Azerbaijan on September 19-20, 2023, the monuments of the Republic of Artsakh now face an imminent threat of destruction. Another incident occurred on September 27, when the Azerbaijani military deliberately targeted the Charektar monastery from the Martakert-Karvachar highway (view the footage here (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zbYhLbwgEzE) - Fig. 7). For further details, please refer to the Monument Watch website: (https://monumentwatch.org/en/alerts/charektar-monastery-targeted-by-azerbaijani-vandalism/).

Bibliography

- Ayvazyan, Sargsyan 2012 - Ayvazyan S., Sargsyan G., Results of excavations and research of Charektar village, VARDZK No. 4, pp. 48-58.

- Charektar Monastery Targeted by Azerbaijani Vandalism-https://monumentwatch.org/en/alerts/charektar-monastery-targeted-by-azerbaijani-vandalism/.

Charektar Monastery: archaeological research

Artsakh