The Early Iron Age burials of Khnapat village

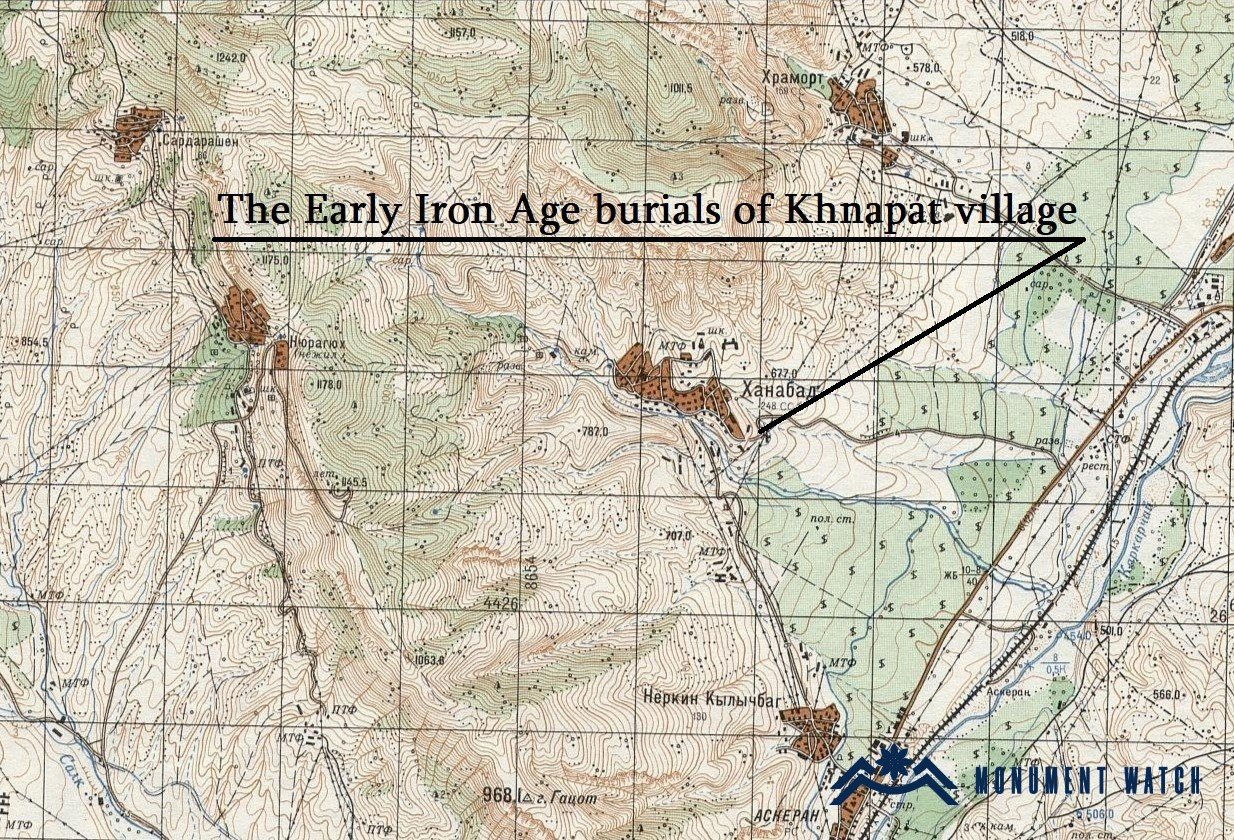

Location

The monument is located at a site known as "Tyuni Baghi Tap," on the eastern outskirts of the village of Khnapat in the Askeran region of the Republic of Artsakh. Since September 2023, it has been under Azerbaijani occupation.

Historical overview

Khnapat is regarded as one of the most ancient settlements in Artsakh. This is attested by burial grounds dating to the second and first millennia BCE, along with the remains of early villages and cemeteries found within the village territory (Safaryan 1992; Sargsyan 2006). According to the Department of Tourism and Historical Environment Protection under the Government of Artsakh, there are 42 registered monuments in Khnapat, including 13th-century khachkars, tombstones, and the “Yereshen” village site, among others(Certificate of Monuments of the Ministry of Education, Science, Culture and Sport of the Republic of Artsakh).

The Archaeological study and examination

The monument was discovered in June 1989 during the construction of a brick factory. It was found that one of the tombs had been damaged during the construction process, rendering the original position of the skeleton indeterminate, as only part of the skull and an arm bone remained in situ. Nevertheless, subsequent archaeological investigations revealed several significant artifacts dating to the 11th–9th centuries BCE. This assemblage comprises a sizable spherical jug, a clay pedestal, a water-bird-shaped vessel, fragments of another decorated vessel, a well-preserved bronze dagger, a staff head, and carnelian beads.

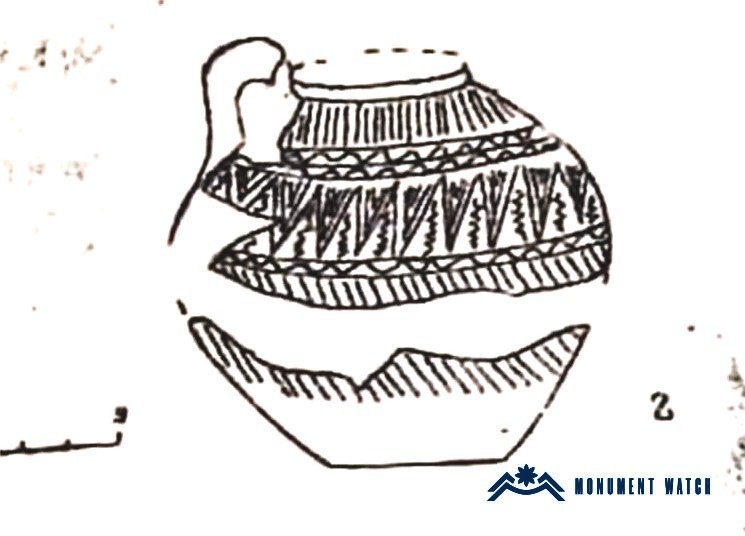

Another black-burnished, two-handled vessel presented in fragments is larger than the previous example and features several ornamental bands (Fig. 3). The decorative elements include linear motifs in the form of chevrons, straight impressed horizontal lines, zigzag lines, and burnishing, primarily concentrated on the upper portion of the vessel. Another relief band, decorated with a single wavy line, encircles the vessel’s widest part. A similar jug was discovered by archaeologist Y. Hummel in Stepanakert in 1938, enabling a precise reconstruction of its shape.

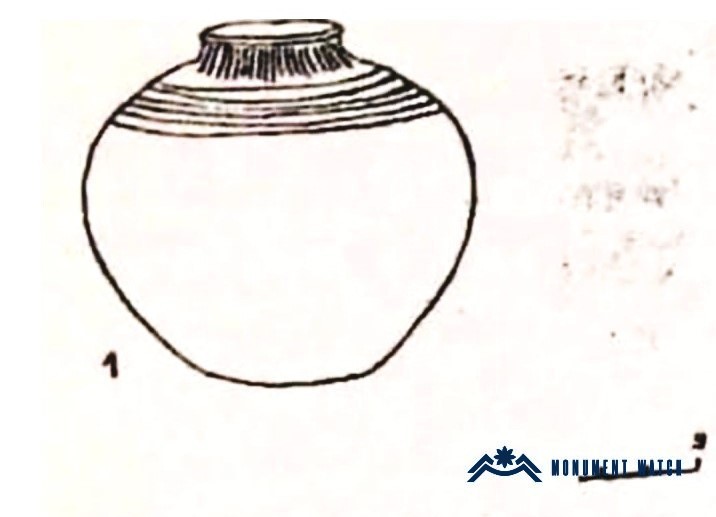

A spherical, handleless jug has a flat base, a short neck, and an outward-flaring profiled rim (Fig. 1). The clay is fine-grained and free of inclusions, with an even firing; the sherd exhibits a brownish hue in cross-section. The upper portion of the vessel is adorned with several horizontal parallel lines forming a band, from which vertical burnished lines descend toward the rim (Fig. 2). Such pottery is characteristic of the 12th–11th centuries BCE.

It is well established that black-burnished pottery with relief ornamentation became widespread during the 12th-11th centuries BCE. This type of ceramic has been identified in the tombs of Artik, Redkin Lager, Dilijan, and Khurjin-hoxer, as well as in the Late Bronze Age pottery from the Tolors Tumulus and within the characteristic Late Bronze Age assemblages of Metsamor (Khanzadyan, Mkrtchyan, Parsamyan 1973, 39-42).

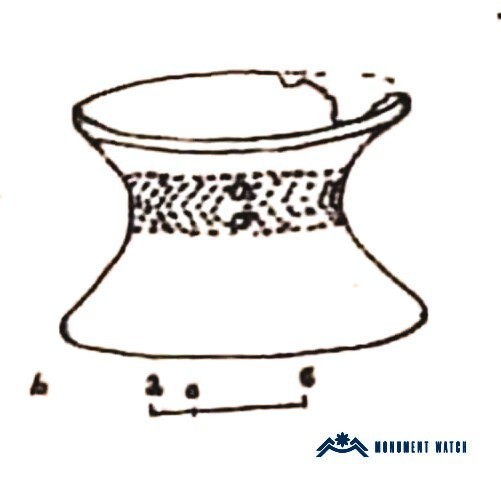

Of particular note among the burial findings is the hollow, double-barreled, black-burnished pedestal censer (Fig. 4), narrowest at the midpoint and widens smoothly toward the ends.

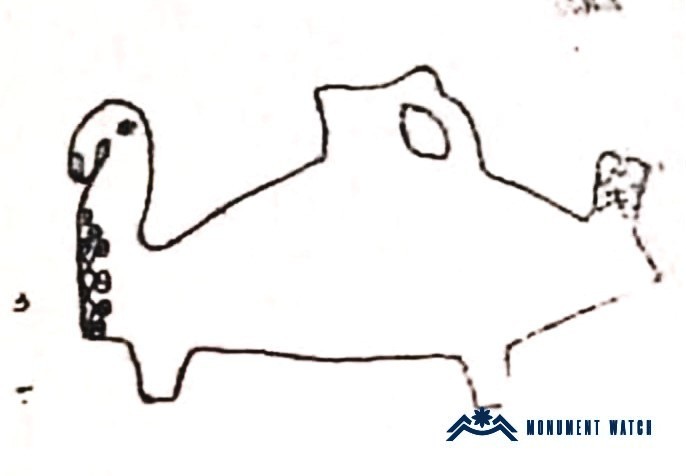

Of particular note is a zoomorphic vessel shaped like a water bird, featuring a dark brown burnished surface (Fig. 5). The “bird” stands on three legs and has a vertically oriented, fin-shaped flat tail, as well as a long neck ending in a flattened head with an elongated, thick beak closely pressed against its neck. Directly below the beak, the bird’s chest is embellished with fifteen concentric circles, and its eyes are indicated by two circular motifs. A small incision, bearing traces of white paste inlay, extends from the top of the head to the midpoint of the beak (Fig. 6).

A considerable number of bird-shaped vessels have been uncovered in the Tepe Sialk necropolis, as well as at Khurvin and Hasanlu (Iran). Zoomorphic vessels have also been documented at various sites in the South Caucasus, including the necropoleis of Mingachevir, Khrtanots, Shikahogh, Khnatsakh, and Tantzaver. The ship presented here is morphologically similar to the horn-shaped cups from the Khurvin collection and the Mingachevir necropolis. However, it is important to emphasize that no identical vessel has been recorded in the archaeological literature. Since it lacks a pouring spout, it was likely not intended for storing liquids. The sooting on the interior and rim of the vessel’s mouth, along with the charcoal remains found between its legs, suggests that it may have served as a censer for burning aromatic herbs or ritual fire.

In various mythopoetic traditions, birds function as symbols of the divine, representing sky spirits, the sun, thunder, wind, the soul, the life force, and more. The conception of the soul in bird form is widespread in ancient traditions. According to the idea that no living being truly dies but only temporarily departs this world-returning to be reborn-“the bird sometimes serves as a person’s helper during ‘second birth’” (Myths 1988, 347). Consequently, one might infer that the bird-shaped zoomorphic vessel under discussion symbolizes the soul of the deceased, intended to aid in its rebirth.

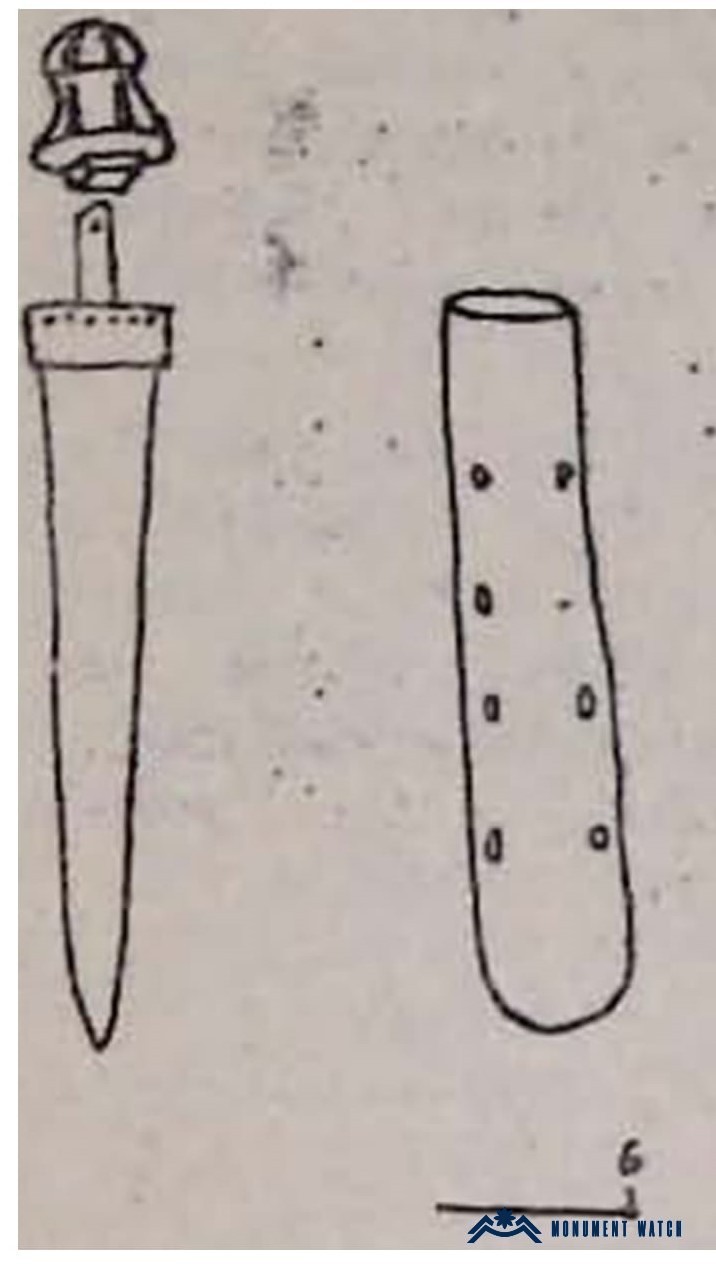

As previously noted, metal objects-a dagger and a staff head-were also uncovered in the burial (Fig. 7). The bronze dagger, classified as the “Sevan” type, features a double-edged, tongue-shaped blade with a central rib, and a conical metal pommel in a lattice design. Such daggers are found in large numbers throughout Eastern, Southeastern, and partly Central Transcaucasia. Similar examples have been discovered in the necropoleis of the villages of Aradjadzor and Akhmakhi in Artsakh and the cemeteries of Tsaghkadzor, Kamo, Astghadzor, Goris, Vanadzor, Tolors, Zardakhar, Mingechevir, Trialeti, and Samtavro. The period of their widest distribution spans the late second millennium BCE and the beginning of the first millennium BCE.

Among the relatively few artifacts, the staff head (Fig. 7) stands out. It is hollow, featuring a cylindrical shaft and a semicircular head, decorated with a series of longitudinal through-holes and raised rhombic motifs. Objects of this kind also became widespread at the end of the second millennium BCE and the beginning of the first millennium BCE.

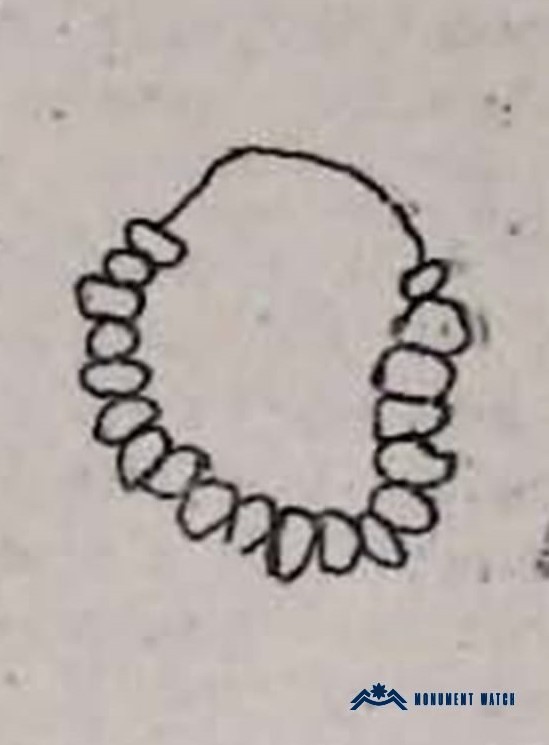

The final group of finds comprises 18 carnelian beads (Fig. 8).

Hence, the morphological analysis of the archaeological material indicates that this burial-discovered by chance-can be dated to the 11th-9th centuries BCE.

The condition before, during, and after the war

Prior to the war, the monument was already in a partially ruined state. There is currently no information available regarding its present condition.

Bibliography

- Safaryan 1992 - Safaryan, V. “Archaeological Find in the Village of Khanabad.” Patma-Banasirakan Handes (Historical-Philological Journal), no. 1, pp. 225-230.

- Khanzadyan, Mkrtchyan, and Parsamyan 1973 - Khanzadyan, E., Mkrtchyan, K., Parsamyan, E. Metsamor. Yerevan.

- Sargsyan 2006 - Sargsyan, S. Khnapat. Yerevan.

- Myths 1988 - Myths of the Peoples of the World, vol. 2. Moscow.

- Certificate of Monuments of the Ministry of Education, Science, Culture and Sport of the Republic of Artsakh- Certificate of Department of Monuments Protection and Study of Tourism Department.

The Early Iron Age burials of Khnapat village

Artsakh