The grave field of Khojalu (Khojaly)

Location

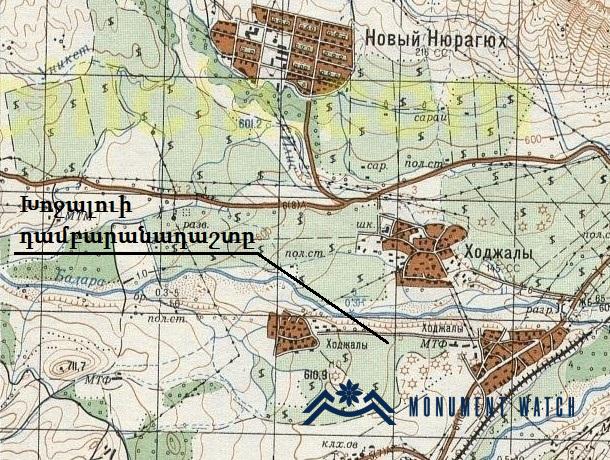

The Khojalu grave field is situated near the village of Ivanyan (formerly Khojalu) in the Askeran region of the Republic of Artsakh, within the Karkar and Badara Mesopotamia. This ancient burial site comprised approximately 100 burial mounds and stone cist tombs, dating back to the Late Bronze and Early Iron Ages (Fig. 1). As of September 2023, the area has been under the control of Azerbaijan.

Historical overview

The Khojalu grave field has been investigated at various times by E. Roessler, I. Meshchaninov, T. Passek, K. Kushnareva, and others. Their findings have been documented in sources such as the "Reports of the Archaeological Commission" for the years 1894, 1895, 1896, and 1897, as well as in publications by Meshchaninov (1926), Passek and Latynin (1926), and Kushnareva (1959, 1970). In 2021, the archaeological expedition from the RA Institute of Archaeology & Ethnography and YSU examined the megalithic structures of the grave field (Avetisyan et al., 2023).

The Archaeological study and examination

The grave field of Khojalu is one of the oldest in the Caucasus, dating back to the Late Bronze and Early Iron Ages. The earliest burials at this site date to the end of the 2nd millennium BC, while the most recent burials are from the 8th-7th centuries BC.

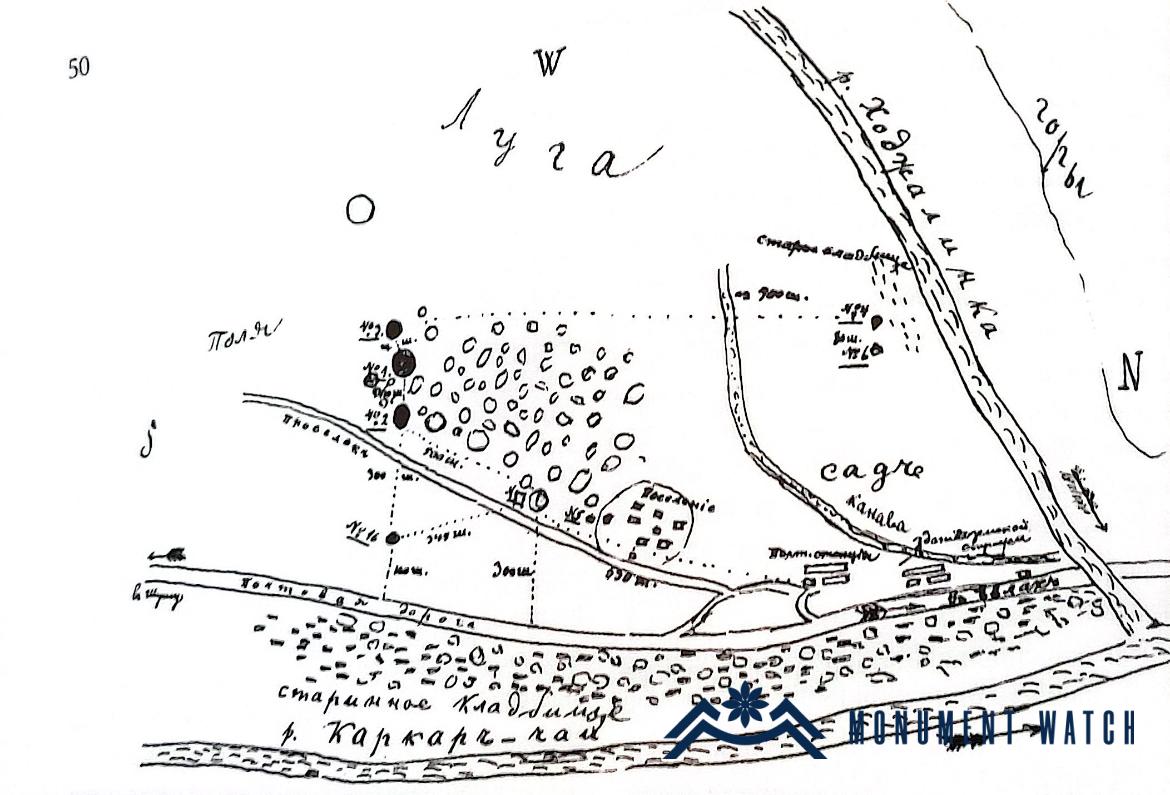

The first excavations of the monument were conducted by Emil Rösler, a teacher at the Shushi Realni School, between 1894 and 1896. Detailed information about Emil Rösler's work can be found in the collection "Zeitschrift für Ethnologie," published in Berlin (Babayan 1895, 37). The excavations enabled E. Rösler to classify the tombs into various types: tower-shaped tombs constructed from river stones, tombs with stone fillings, large tombs covered with sand, tombs with stone fillings, and tombs without a cell (Avetisyan et al. 2023, 50; fig. 2).

In the following years, the monument underwent repeated examinations by various specialists. In the 1920s, I. Meshchaninov studied the burial ground and the two menhirs located near the Hacha-tepe burial mound (Fig. 3). The excavated material by Emil Rösler was further analyzed and summarized by K. Kushnareva (Kushnareva 1970). In the cemetery of Khojalu, K. Kushnareva identified 3 groups of burial mounds.

- Small earth burial mounds with private burial chambers dating from the 13th to 11th centuries BC (Numbers 5, 14, 16).

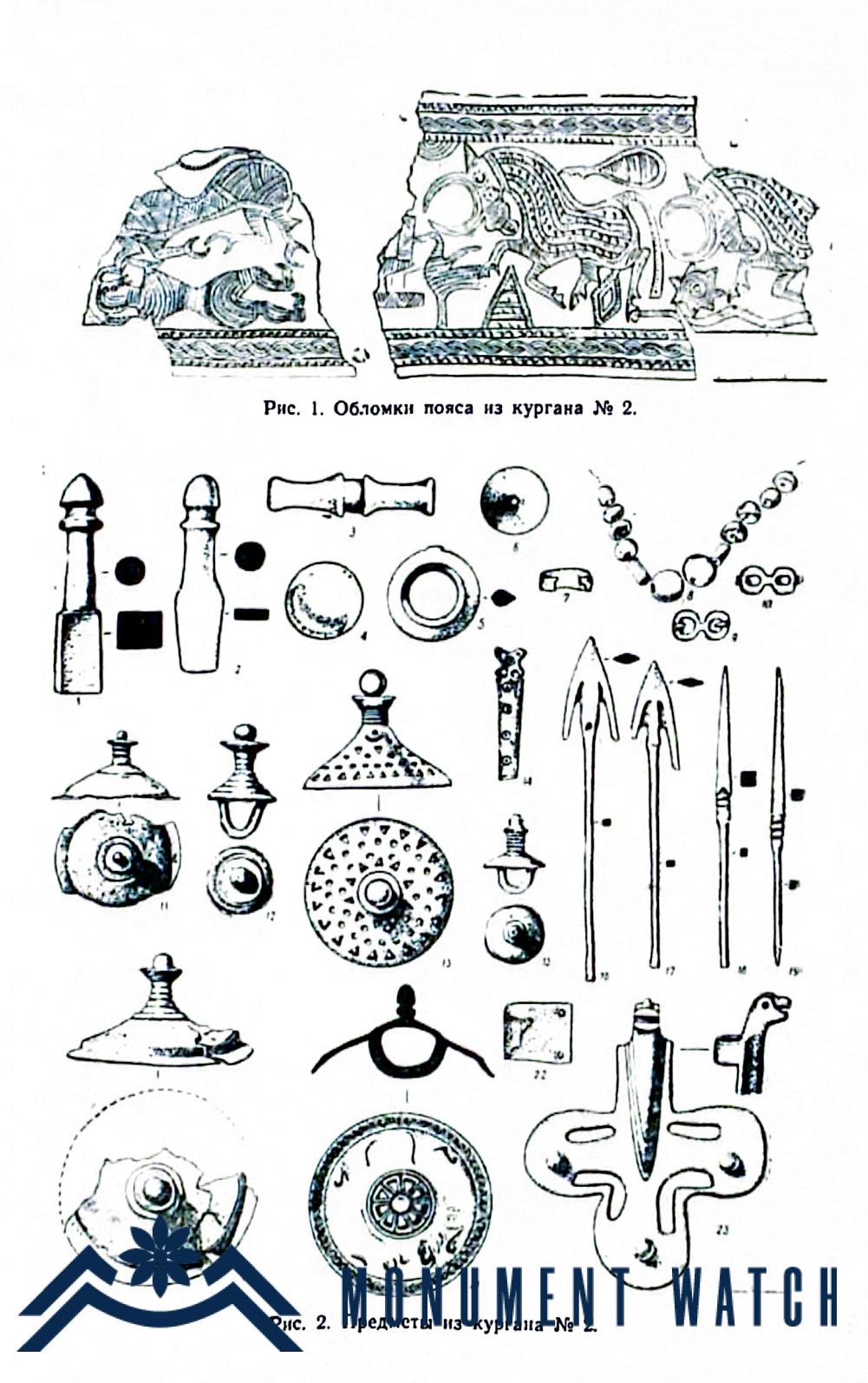

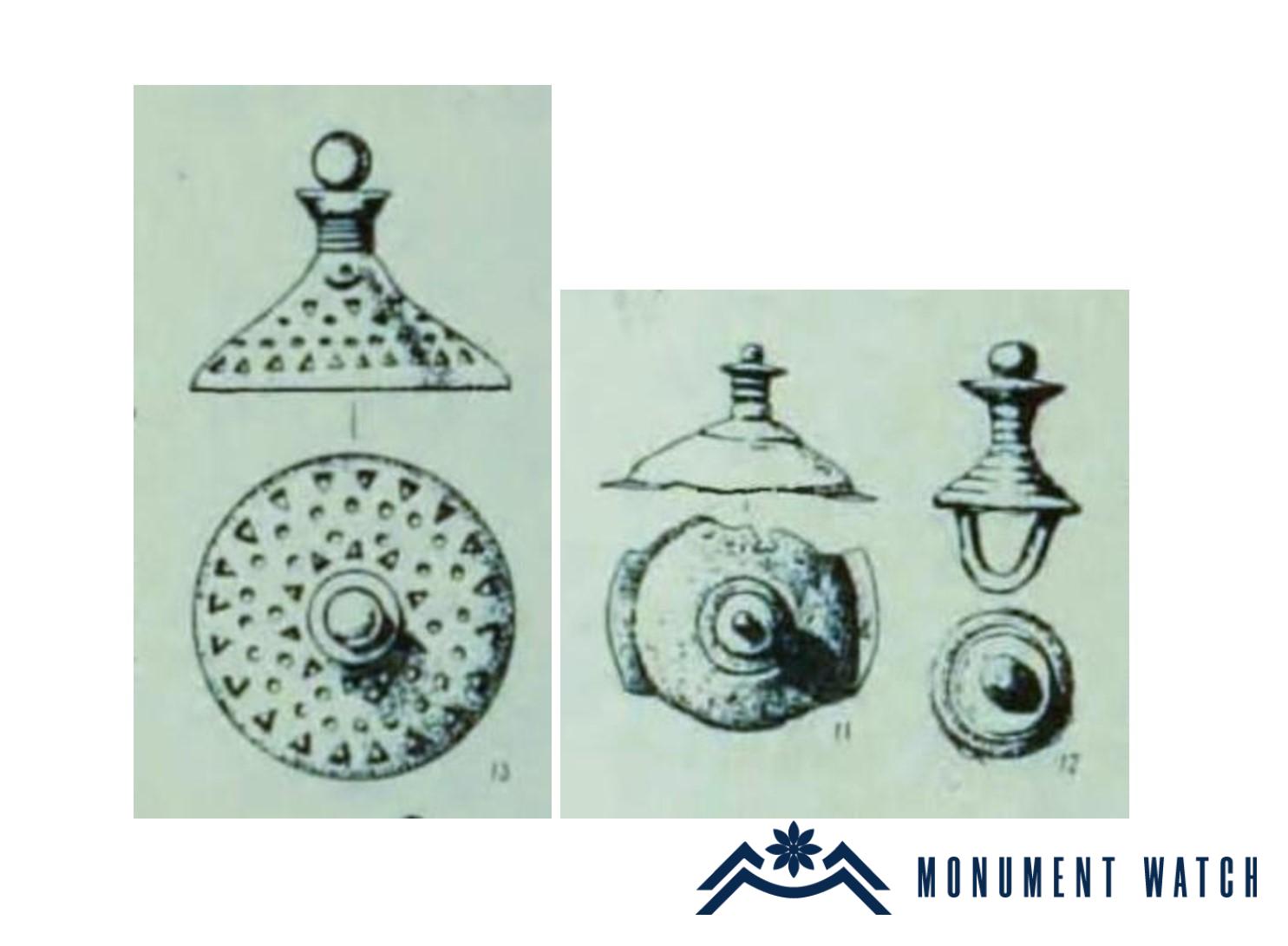

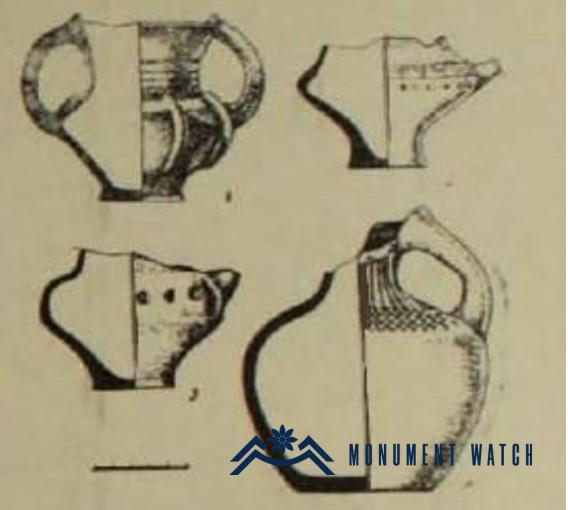

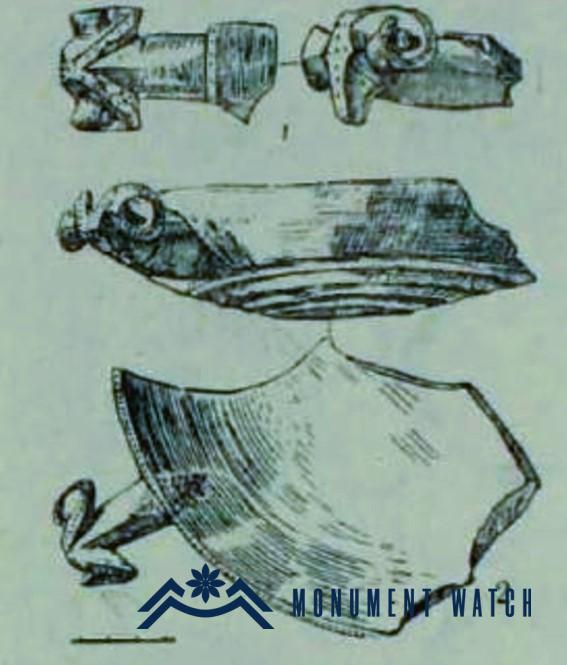

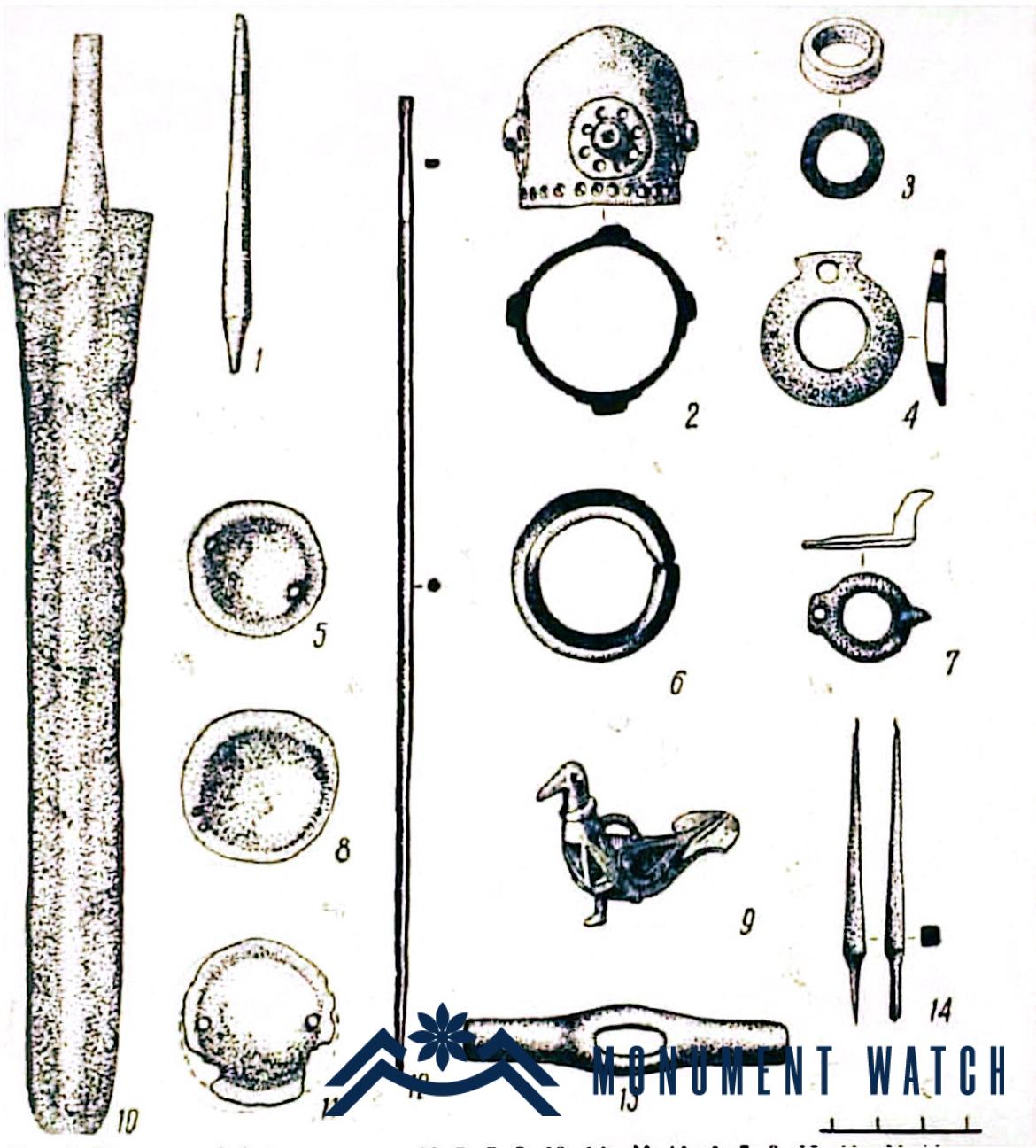

- Large earthen burial mounds with traces of cremation, dating from the 10th-9th centuries BC. Two of these mounds, numbers 1 and 2, were excavated by Emil Rösler. The second burial mound was particularly interesting, as human and animal bones, pottery fragments, and carnelian beads were discovered at a depth of 1 meter. After that, a two-meter layer of soil and ash was found, which can be considered the result of cremation. Within this layer, human and animal bones were discovered, along with a square bronze pot, parts of a bronze belt—one depicting mythical bulls and the other a man lying on the ground with weapons and armor—40 bronze arrows, buckles (Fig. 4), black-glazed jars (Figs. 5, 6), and carnelian and paste beads (Kushnareva 1970). An interesting feature of Khojalu's second burial mound is the burial of a bull (or bulls), whose skull, according to E. Rösler, was adorned with two bronze headbands (Kushnareva 1970; fig. 7).

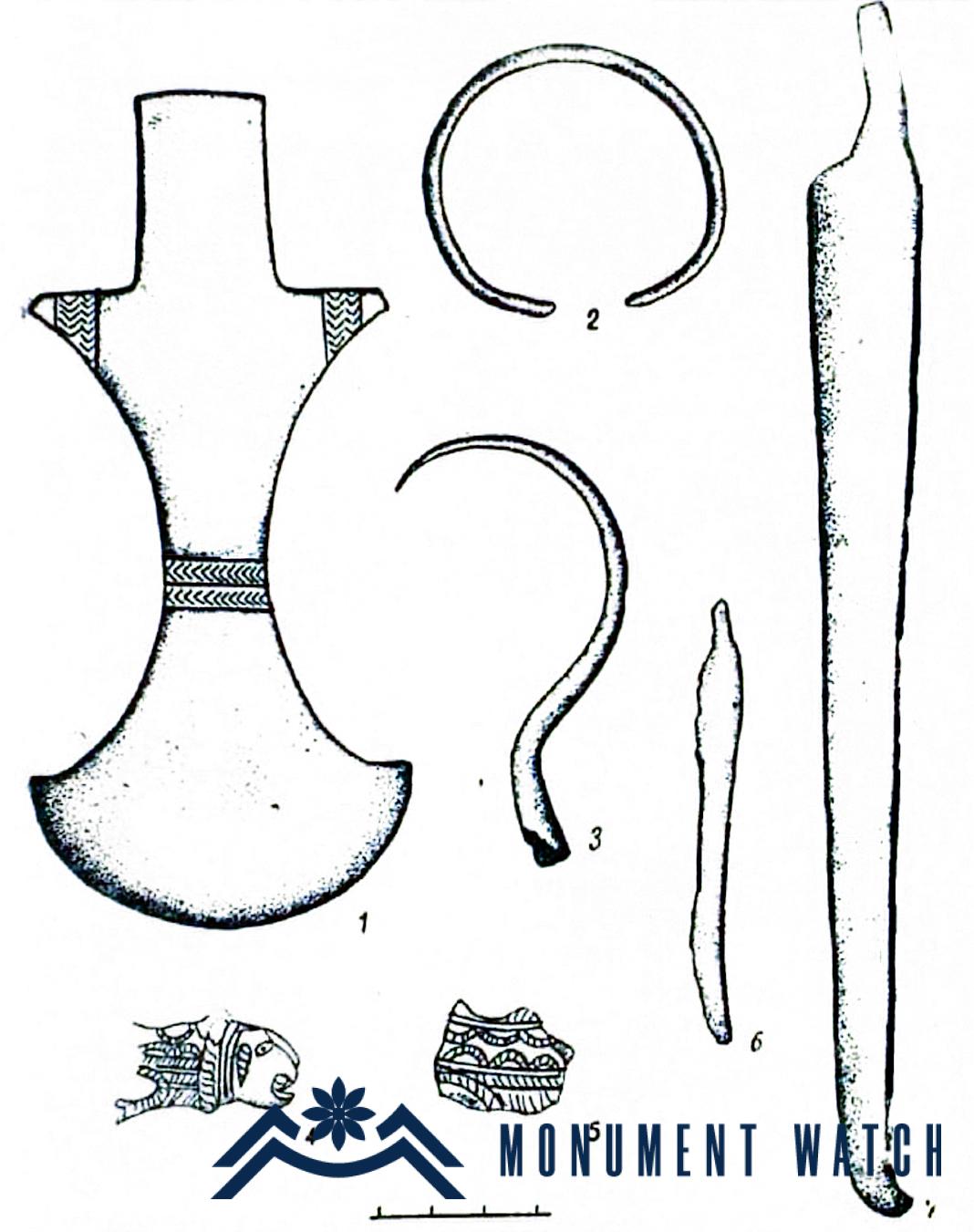

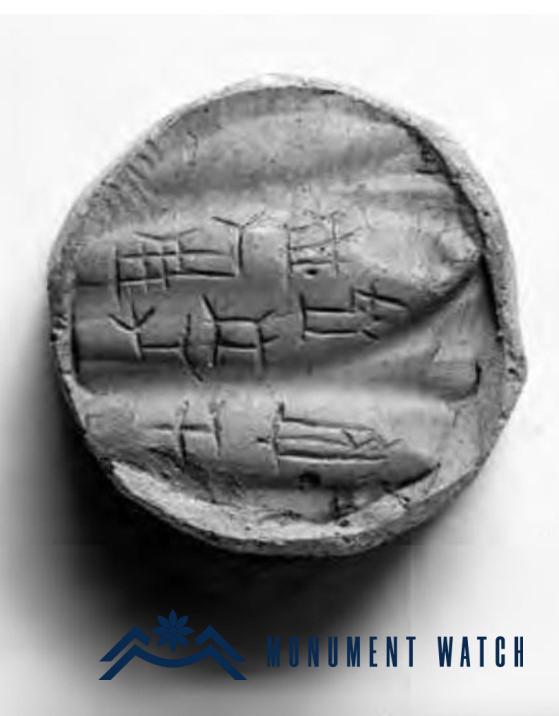

- Kushnareva also identified stone-filled burial mounds with stone cist chambers dating from the 8th-7th centuries BC (numbers 7, 11, 19, 20). Items found in these burials include pieces of a bronze belt, bracelets, gold jewelry, sardine beads (Figs. 8 and 9), and a staff head featuring a horn (Kushnareva 1970; fig. 10). The most interesting material was found in burial mound No. 11, the most significant being a seal with an Assyrian inscription (Kushnareva 1970; fig. 11). In ancient times, such seals were used to seal contracts and goods acquired through commercial transactions. According to I. Meshchaninov, the found seal is older than the burial in which it was discovered, suggesting it was likely kept for a long time by members of a clan before being placed in the grave (Meshchaninov 1926, 217).

- The burial mounds of the Early Iron Age (numbers 1, 2, 18) have a diameter of 76-88 meters and a height of 8-10 meters, with cremation being the primary burial rite. In contrast, the burial mounds from the period of widespread use of iron (numbers 7, 11, 14, 19) have a diameter of 12-48 meters and a height of 2-8 meters, with the burial rite involving burial in a stone box.

The cemetery of Khojalu is a unique monument. Analysis of the structure and archaeological material of the various types of burial mounds indicates that this burial ground was created gradually over several centuries, from the end of the 2nd millennium BC to the 8th-7th centuries BC (Kushnareva 1970, 122).

The condition before, during, and after the war

During the construction of the airport during the Soviet years, some burial mounds were damaged. Before the war, the monument was in good condition. After the 44-day war, Russian peacekeepers were stationed next to the mausoleum.

Bibliography

- Imperial Archaeological Commission 2019 - Imperial Archaeological Commission, Reports of the Archaeological Commission for the years 1859-1917, Moscow․

- Meshchaninov 1926 - Meshchaninov I., Brief information about the work of the archaeological expedition in Nagorno-Karabakh and Nakhichevan region, vol. I, Baku.

- Passek, Latynin 1926 - Passek T., Latynin B., Khojalu mound No. 11, News of the Society for Survey and Study of Azerbaijan, vol. I, Baku.

- Kushnareva 1959 - Kushnareva K., Archaeological work in the vicinity of the village. Khojalu, Materials, and research on the archeology of the USSR, vol. 67, Moscow, p. 370 - 380.

- Kushnareva 1970 - Kushnareva K., Khojalu burial ground, Historical and Philological Journal, No. 3, Yerevan, p. 109-124.

- Babayan 1895 - Babayan L., Tombs of Khojallu, Ethnographic Journal, No. A, pp. 37-40.

- Avetisyan and et al. 2023 - Avetisyan H., Gnuni A., Sargsyan G., Mkrtchyan L., Bobokhyan A., Megalithic culture of Artsakh, Yerevan.

The grave field of Khojalu (Khojaly)

Artsakh