The Iron Age Tombs of Shushi

Location

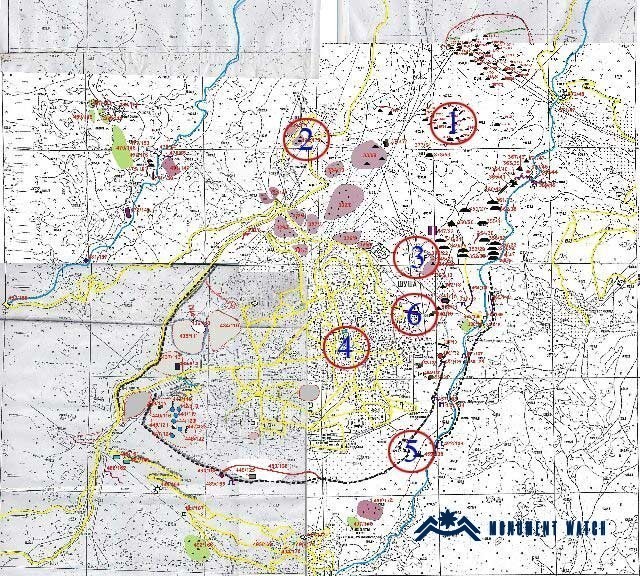

The Shushi necropolises are situated on the northern and northeastern slopes of the Shushi plateau in the Republic of Artsakh (fig. 1). Following the 44-day war of 2020, both the plateau and the city fell under Azerbaijani occupation.

Historical overview

Emil Rösler, a teacher at the Shushi Realni School, conducted the initial excavations of the Shushi plateau necropolises in 1891 (Dluzhnevskaya, 2014).

In 2004, an archaeological expedition from the Institute of Archaeology and Ethnography of the National Academy of Sciences of Armenia, invited by the authorities of Artsakh, conducted field surveys to compile a catalog of the archaeological monuments of Shushi and its immediate surroundings (Dluzhnevskaya, 2014). This catalog encompassed approximately 500 monuments from the Paleolithic period to the early 20th century, accompanied by a distribution map (fig. 1). In 2005, the expedition undertook extensive excavations in Shushi and its surrounding areas. The findings from these excavations offer compelling evidence that Armenian cultural identity existed on the Shushi plateau for a minimum of 500 years prior to Panah Ali Khan's arrival and continued until the mid-18th century (Petrosyan 2007, 430).

Architectural-compositional examination

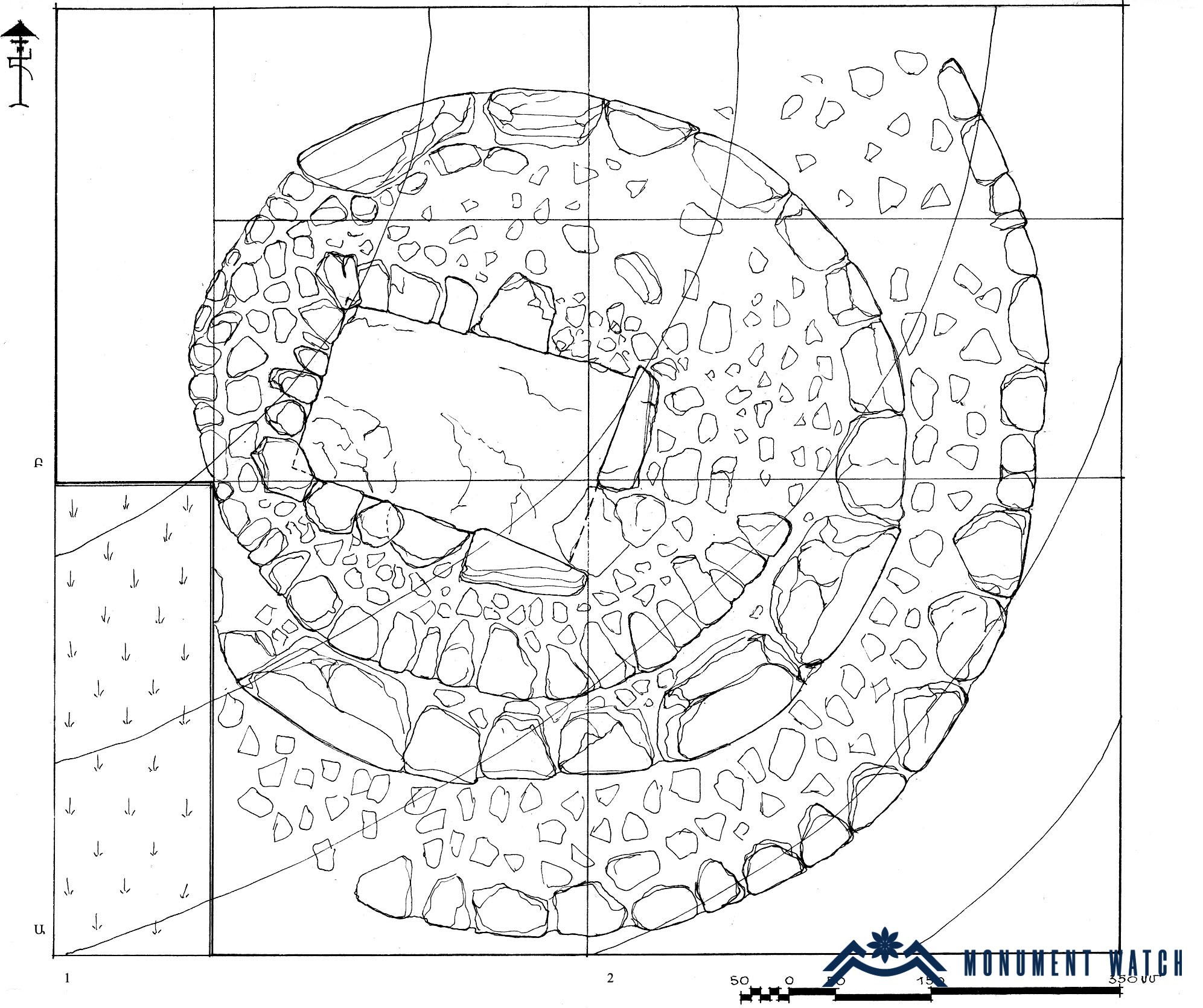

In 2005, excavations were conducted in each necropolis adjacent to Shushi, located to the north and east. In the northern necropolis, the partially destroyed Tomb No. 61 was selected for excavation to prevent further destruction (fig. 2). The tomb's enclosure comprised two concentric rows of cromlech constructed with contiguous stones of varying sizes. The first row comprised several vertical stone slabs, while the northern stones were absent. The arrangement of rocks in the second cromlech row exhibited a spiral pattern ( figs. 3 and 4) (Yengibaryan, Titanyan 2007, 260).

The burial chamber itself was found to be devoid of cover slabs. Archaeologists uncovered an iron spear and a silver-engraved decorative plate in the northern section of the second cromlech row. Further discoveries in the vicinity of the cromlech stones on the western side included a bronze bell and two bracelets. During the cleaning process of the burial chamber, artifacts recovered at different levels included an obsidian arrowhead and beads (Fig. 5).

The chamber is a rectangular stone cist, its walls constructed of medium-sized stones and several stone slabs. At the same time, the floor consists of bedrock (fig. 6). Among the weapons unearthed from Tomb No. 61 is an iron spear featuring a tubular socket and a blade with a pronounced midrib, a type of armament commonly attested at sites dating to the 8th-6th centuries BCE. Similar spears have been documented at Golovino, Ghachaghani, Tsaghkashat, and Harjis, dating back to the 7th-6th centuries BCE.

The next discovered weapon is an obsidian arrowhead with a rectangular perforation at its base and carefully retouched edges. This type of weapon is known from the earliest phase of the Bronze Age and, though in smaller numbers, continues into the first half of the 1st millennium BCE. Comparable artifacts have been found at contemporaneous sites such as Astghadzor, Vardenis, Karchaghbyur, and elsewhere (Yengibaryan, Titanyan 2007, 261-262).

Among the metal finds, a bronze-cast bell is of particular interest. A fine dotted line encircles its lower rim, and small openings below the circular loop once held a rod from which the clapper was suspended. Bells appeared north of the Araxes River as an element of chariot and horse gear beginning in the 8th century BCE (Yengibaryan, Titanyan 2007, 262).

The serpent-headed bracelets from the tomb are composed of thin bronze wire and are adorned with short incised strokes (fig. 7). The depiction of the snakes' heads is notable for its use of schematics. Of additional interest are the snail shells utilized as pendants and the beads crafted from carnelian, paste, and bronze (Yengibaryan, Titanyan 2007, 263).

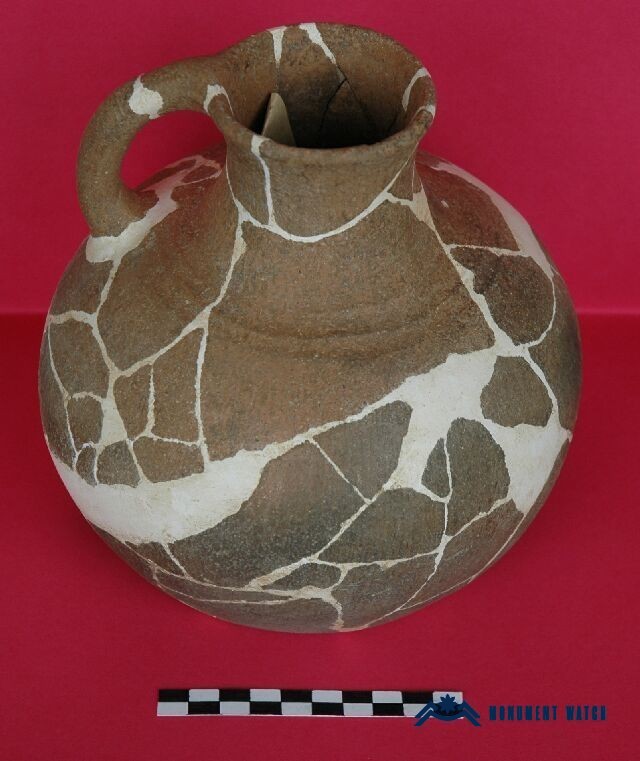

The ceramics from the site predominantly consist of pitchers, pots, and bowl lids, primarily in gray and brown hues, suggesting either the use of a potter's wheel or hand-building techniques. The recovered fragments of the neck, rim, and handle of single-handled pitchers indicate narrow-necked forms with wide mouths, dating to the 8th–6th centuries BCE. The handles of these artifacts typically connect the rim to the upper body of the vessel (see Figure 8). The handles are either bow-shaped or feature a central protrusion. Some of these handles exhibit signs of twisting or are adorned with protrusions or additional "buttons" (Fig. 9).

A distinct group consists of pots-thin- or thick-walled, hand-built vessels with gray, brownish, or yellowish surfaces. Both the pitchers and the pots are adorned with incised, burnished, or stamped wavy lines, "grain-like" patterns, oblique lines, cross-hatched burnishing, or horseshoe-shaped applied ornaments (fig. 10; Yengibaryan, Titanyan 2007, 263–264).

Another major ceramic group comprises numerous bowl lids featuring brown, gray, or black surfaces, typically with straight or slightly inward-curving rims. These artifacts are distinguished by their ring-shaped, semicircular, or protruding handles, which are positioned vertically or horizontally along the rims or bodies of the vessels. An exemplar of this variety is adorned with incised wavy lines and motifs of the Tree of Life (Fig. 12).

The vessel spouts, some of which terminate in a stylized animal head (Fig. 11), are particularly noteworthy.

Tomb No. 61, with its assemblage of artifacts and their decoration, resembles the material from Harjis. Additionally, its three-footed bowl-lids and single-handled pitcher’s parallel items from Aghitu dating to the 8th-6th centuries BCE (Yengibaryan, Titanyan 2007, 264).

The second excavated tomb (No. 175/1) is situated in the northeastern necropolis, on the slope of the second of three hills that lie to the right of the Stepanakert-Shushi road (fig. 12). The stone-and-earth fill is ring-shaped, consisting of medium-sized stones placed at regular intervals. From this fill, an obsidian blade and several pottery sherds were retrieved. The tomb’s cover slabs were missing, filling the chamber with small stones. The burial chamber is a rectangular stone cist (fig. 13). Fragments of a brown single-handled pitcher and a pot were discovered at various levels in the northern half of the chamber.

In the vicinity of the southern wall, situated on the ground, were fragments of a black vessel, a staff head, a bracelet, and a carnelian bead, all of which were in a state of poor preservation (fig. 14). Among these fragments, the staff head merits particular attention due to its distinctive characteristics. It has a hollow cylindrical body and a semicircular head adorned with longitudinal perforations and protruding rhombus-shaped elements. Objects of this type became widespread in the early 1st millennium BCE and served as symbols of authority (Yengibaryan, Titanyan 2007, 265). Parallels can be found at Ltsen, Balukay, Khanabad, and elsewhere. The tomb is dated to the 10th-8th centuries BCE based on the recovered materials.

The condition before, during, and after the war

The tombs were in good condition prior to the war. However, following the 44-day war, the entire territory of Shushi came under Azerbaijani control.

Bibliography

- Dluzhnevskaya G. Archaeological Research in the European Part of Russia and in the Caucasus, 1859-1919 (Based on Documents from the Scientific Archive of the Institute of the History of Material Culture, Russian Academy of Sciences), St. Petersburg: LEMA, 2014.

- Yengibaryan N., Titanyan M. The Iron Age Tombs of Shushi, Shushi According to Archaeological Research: Shushi, the Cradle of Armenian Civilization, materials of the conference dedicated to the 15th anniversary of the Liberation of Shushi, Yerevan, 2007.

The Iron Age Tombs of Shushi

Artsakh