The Khachkars of Amaras Monastery, Surb Grigoris’ Tombstone, and Inscriptions

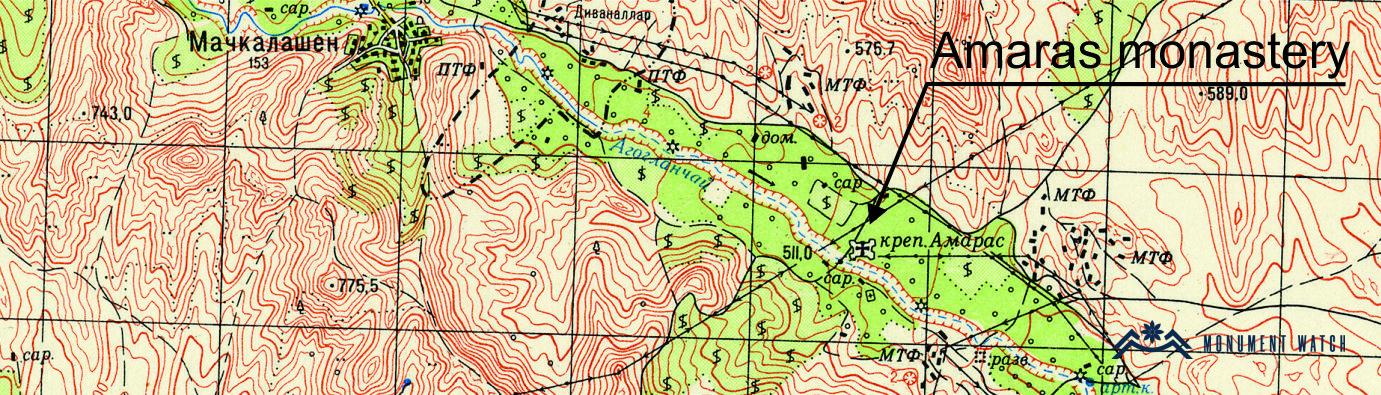

The Amaras Monastery is one of the complexes that have undergone significant changes over time in Artsakh. Its original church, which existed as early as the 4th century when the remains of Grigoris were buried, was no longer present by the end of the 5th century when his relics were discovered. The above-ground portion of Grigoris' shrine was also gradually destroyed over time. In the 17th century, a domed church was constructed on top of its underground section, and in the mid-19th century, the current church was built on the same site. During the 17th and 18th centuries, the existing fortress and economic structures were built and later underwent modifications in the 19th century. As a result, the monastery's graveyard, along with most of the old monuments, tombstones, and inscriptions, gradually disappeared over time.

The Khachkars

Today, only two khachkars are known from Amaras Monastery. The first of these, which is remarkably well-preserved, was transported to the village of Kolkhozashen in the 1960s and subsequently installed within the courtyard of the Surb Astvatsatsin church in the village. This khachkar represents a classic example from the 11th century (Fig. 1).

Depicted in a square niche, it features a cross with wings, designed in the shape of trefoils, set upon a stepped elevation representing Calvary. Light symbols adorn the border and are positioned on both sides of the inner arm of the cross. Notably, the cornice and the upper section of the cross are adorned with intricate fruit designs, including grape clusters and pomegranates. Additionally, the khachkar exhibits sculptures of birds delighting in the grapes (Fig. 2).

The inscription on this khachkar is particularly noteworthy, as it also discloses the names of the khachkar and the artisan responsible for its creation: "Surb Astvatsatsin, in the year 1091 of the Armenian calendar, I, Abraham, the elder priest, constructed this. Remember me in your prayers to the Lord. I, Ghazar, compiled this. Remember me in your prayers to Christ and the Lord "(Fig. 3). It's worth noting that the Armenian date is exclusively employed in the inscriptions of Artsakh, Utik, and Caucasian Albanian regions. This fact serves as evidence of the calendar unity between the Armenian and Caucasian Albanian churches.

The upper section of a khachkar, dating back to 1205, serves as an ornament inside the north wall of the current church, and it has also been preserved from Amaras (Fig. 4).

Only the inner part of the monument has survived, including a portion of the vertical borders, a sculpture, and an inscription. It had been previously concealed under a thick layer of plaster, which resulted in considerable damage to the sculptures and the inscription during its clumsy removal. The composition of the Khachkar itself can only be deduced from the remnants of the border bands, which depict Artsakh in the 12th-13th centuries. These khachkars feature a prevalent meander chain with protrusions that culminate in pomegranate fruits. Additionally, in the surviving sculpture, the pomegranates are arranged in a manner that conveys the impression that the people represented in the artwork are sheltered beneath a canopy of pomegranate-laden branches. These sculptures closely resemble the khachkars found at the Bri Yeghtsi monastery, sharing a distinctive feature of incorporating pomegranate fruits throughout their composition. In contrast to the conventional khachkar design where pomegranates, along with grape bunches, typically occupy the upper corners, these sculptures deviate from the norm by distributing pomegranates throughout the composition.

The depiction of pomegranate fruits was a common motif in khachkar art. In terms of how often it was presented, this motif was perhaps second only to grape clusters. A closer examination reveals that pomegranate fruits in khachkar compositions are intertwined with both folk and Christian symbolism, akin to grapes, reflecting the symbolic connection between wine and blood in certain instances. In another context, pomegranate fruits symbolize the Christian idea of the contrast between the outer "bitter shell" and the inner "sweet grains." In a third scenario, they may simply represent the idyllic garden-paradise setting, aligning with the redemptive symbolism often found in khachkar art (Petrosyan 2008, pp. 349, 352).

The sculpture portrays two men seated on thrones, while a youth stands before them, serving wine. All three figures are attired in the traditional clothing of the 12th-13th centuries, characterized by wide chukhas that extend below the knees and adorned with wide belts featuring decorative fringes. They also wear hats with conical stems, spherical protrusions, and "braids" extending from the sharp edges of the stems to their shoulders. This clothing represents the typical attire of men during that era, well-suited for riding and battlefield activities, and was commonly worn during this period. The fact that children's clothing closely resembles adult attire in similar compositions underscores the profound symbolic significance of this clothing complex. The act of pouring and drinking wine in such solemn and ritualized scenes, as revealed through a thorough iconographic and semantic analysis, is deeply rooted in the fundamental belief that ritualized wine consumption was seen as the perfect means to connect with the divine essence and, in turn, achieve immortality. The fact that children's clothing closely resembles adult attire in similar compositions underscores the profound symbolic significance of this clothing complex. The act of pouring and drinking wine in such solemn and ritualized scenes, as revealed through a thorough iconographic and semantic analysis, is deeply rooted in the fundamental belief that ritualized wine consumption was seen as the perfect means to connect with the divine essence and, in turn, achieve immortality. Conversely, the seating arrangement of the adults and the positioning of the youth at the center of the composition suggest that this could be a "family portrait." This theme is a recurring motif in Artsakh's khachkar sculpture, primarily intended to depict the deceased within a familial and affectionate setting (Petrosyan, Yeranyan 2022, 41-42).

Despite the damage to the Khachkar inscription, there is potential for restoration. The inscription reads: "In the year 1205, please remember Gortsogh and Anayser in your prayers."

As we've observed, in 1091 in Amaras, the khachkar master granted himself a title. It's tempting to speculate that here, we're also encountering the master's "working" title (as Gortsogh also means doer or worker in Armenian.) However, the inscription's structure leans more towards identifying the names of the individuals for whom the khachkar is dedicated. These names correspond to the figures represented in the iconography, embodied in the form of the Gortsogh and the Anayser names.

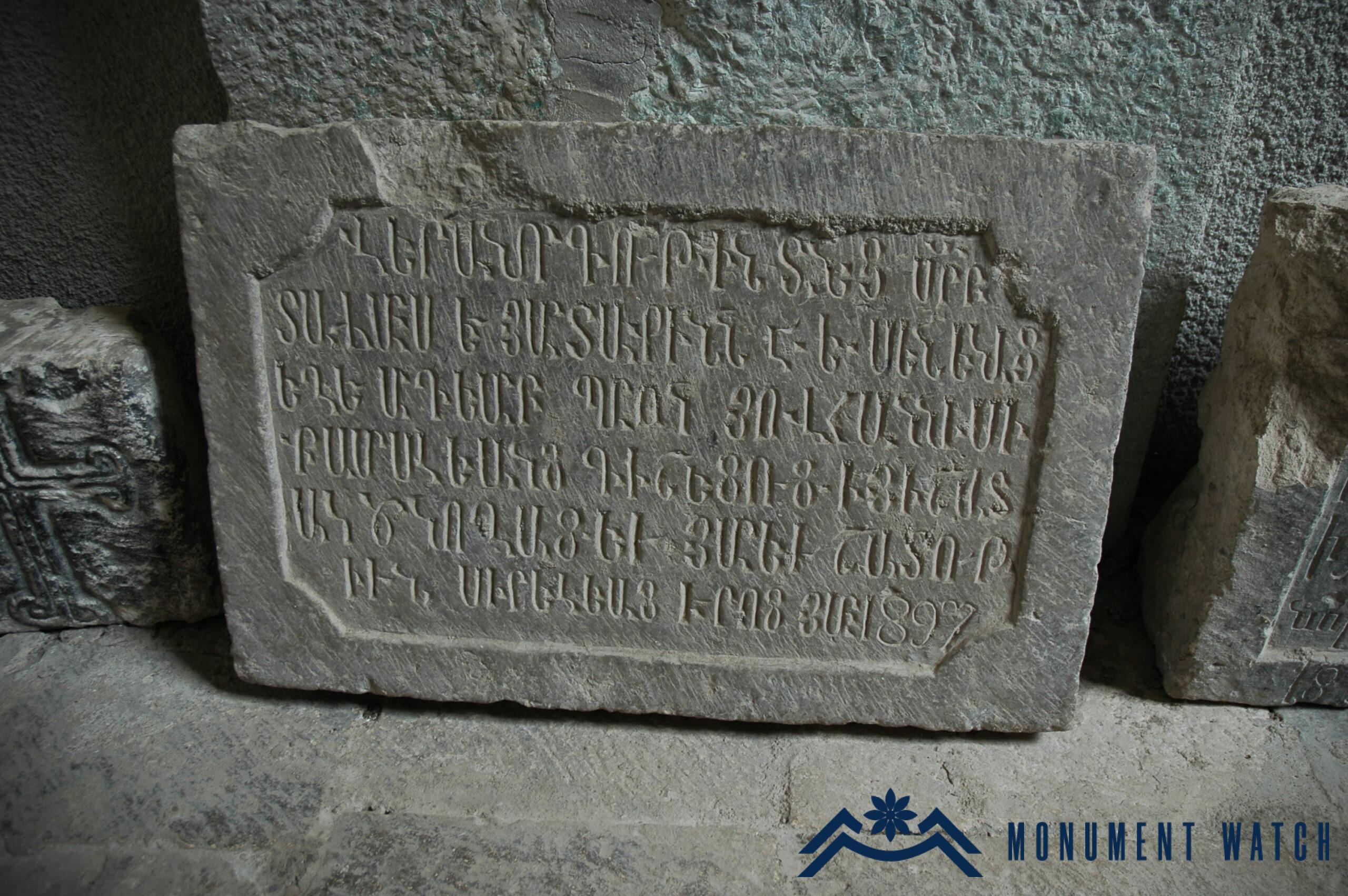

The "tombstone" of Surb Grigoris

The "tombstone" of Surb Grigoris stands out (Figs. 5, 6). As we mentioned (https://monumentwatch.org/en/monument/the-shrine-of-st-grigoris-in-amaras/), no tombstone is mentioned in the description of the discovery of the relics of Grigoris. The remains of Grigoris are buried underground. The relics are separated, and a portion is kept in a shrine that was built for that specific purpose, most likely in a special cabinet. The "tombstone" for Grigoris was created towards the end of the 19th century, as indicated by the inscription on it: "This stone statue of Surb Grigoris, crafted by Mikael Ter Israeleants from Shushi, in memory of his deceased and living, on November 1, 1889 "(Lalayan 1897, 38).

It takes the form of a slab with a table-like structure. On its upper surface, it features depictions of the patriarchal hood, cane, and a cross. Below this representation, on the southern side, there is a substantial inscription that likely tells the traditional tale or narrative associated with the saint: "This is the tomb of Surb Grigoris, the Catholicos of Caucasian Albania and the grandson of Surb Gregory the Illuminator. He was born in 322, consecrated in 340, and martyred in 348 by King Sanesan in the Vatnyan field, near Derbend. His holy relics were subsequently transported to Amaras by the student deacons of Artsakh." The original tombstone was destroyed by the Azerbaijani Special Purpose Police Unit (OMON) forces in 1990 when the monastery fell under their control. However, in the 2000s, a replica was crafted and installed in the shrine to replace the lost tombstone.

Other inscriptions

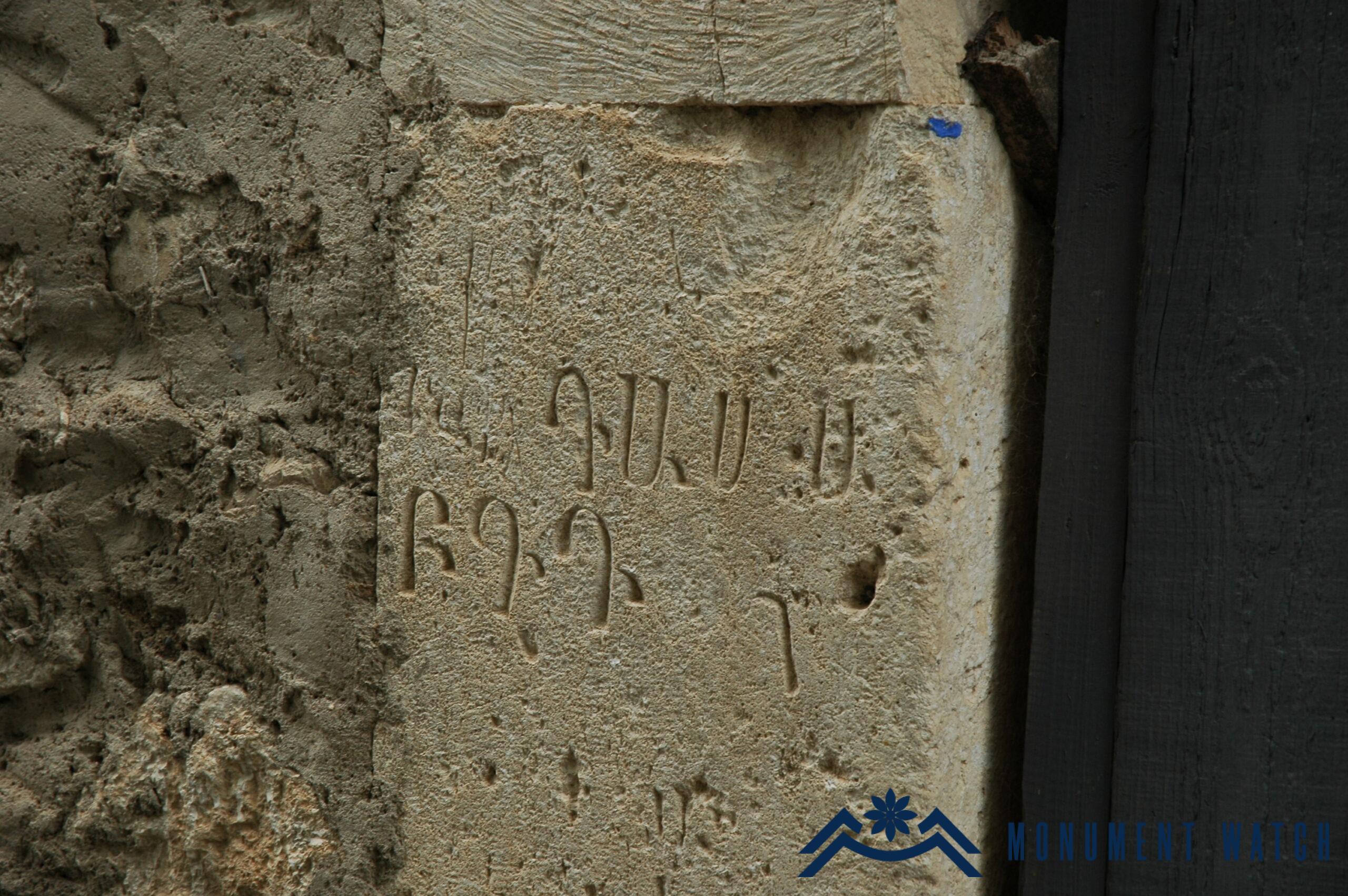

Numerous Construction and Memorial Inscriptions are Evident on the Residential Structures of the Monastery, as well as on Slabs that have since Fallen. Notably, we find one such inscription on the entrance hall of a room. The inscription reads: "In memory of this diocese leader, Vardapet Kasbar, in the year 1740 (Fig. 7).

Several inscriptions from the late 19th century record room renovations. Notably, an inscription on one of the structures conveys this information: "For the memory of the soul of Sophia Khanum from Shushi, who renovated these two rooms in memory of the deceased, on November 25, 1890 "(Fig. 8). Another inscription is as follows: "The renovation of the five outer rooms of this sacred temple was carried out through the benevolence of Yovhannes Kamaleants in memory of his parents and for the well-being and longevity of his beloved ones, in the year 1897"(Fig. 9). Short inscriptions left by various visitors have also been preserved on the walls of different structures within the monastery. These inscriptions include phrases such as "Holy Amaras" and "in the monastery of Amaras" (Fig. 10, 11), among others.

An inscription engraved on one of the slabs is particularly notable and likely associated with the traditional attribution of a school to Mesrop Mashtots in Amaras. This inscription reads "Class. a, b, c, d" (Fig. 12). Additionally, it's worth noting the plaster inscription on the ceiling of the great hall in the south, where only the phrase "Son of God" is discernible (Fig. 13).

Bibliography

- Lalayan 1897 - Lalayan E., Varanda, Ethnographic Journal, No. 2, Tbilisi.

- Petrosyan 2008 - Petrosyan H., Khachkar, origin, function, iconography, semantics, Yerevan, Printinfo.

- Petrosyan, Yeranyan 2022 - Petrosyan H., Yeranyan N., Monumental Culture of Artsakh, Yerevan, Antares.

The Khachkars of Amaras Monastery, Surb Grigoris' Tombstone, and Inscriptions

Artsakh