The Surb Hovhannes Church Complex in Togh

Location

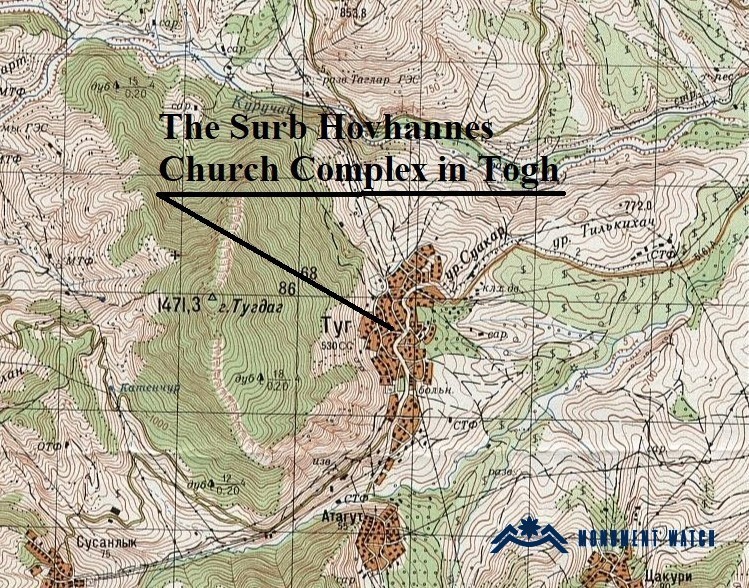

The Surb Hovhannes Church is located in the center of the village of Togh (Dogh) in the Hadrut Region of the Republic of Artsakh (Nagorno-Karabakh), approximately 50 meters southwest of the Melik Yegan Palace, situated on a sloping terrain. The northern wall of the church is built into the rock for about half its height, while the southern wall is completely open, revealing the foundations. A walled courtyard, enclosed by a perimeter fence, adjoins the church on its southern and northern sides (Fig. 1). Presently, the entire complex is occupied by Azerbaijani forces.

A Brief Historical overview

Our knowledge of Surb Hovhannes Church's history primarily derives from inscriptions preserved in situ and from material culture finds. A substantial inscription on the cross pedestal of the church records:

"In the year 1736, the roof of this Holy Surb Hovhannes Church was renovated by Melik Yegan, son of Vardapet Ghukas, in commemoration of his soul. Whoever reads (this) once, may God have mercy—say Amen." (Fig. 2).

Thus, in the eighteenth century, the roof was renewed by Melik Yegan (DhV 1982, 178). According to Bishop Makarios Barkhudaryants, however, the church itself originally dates to the thirteenth century (Barkhudaryants 1895, 75). Physical evidence of an even earlier sanctuary has been discovered: on the right side of the bema, opposite the apse entrance—slightly elevated above the nave floor—one can observe the massive shaft of a thick drum-shaped column (Mkrtchyan 1985, 97), indicating the presence of a preexisting worship space.

More recent studies have demonstrated that Surb Hovhannes Church was constructed in the seventeenth to eighteenth centuries and functioned as the village's parish (gahanist) church (Yeranyan & Petrosyan 2022, 38). Like the nearby Melik Yegan Palace, this church originally featured a surrounding battlemented curtain wall.

Architectural-compositional examination

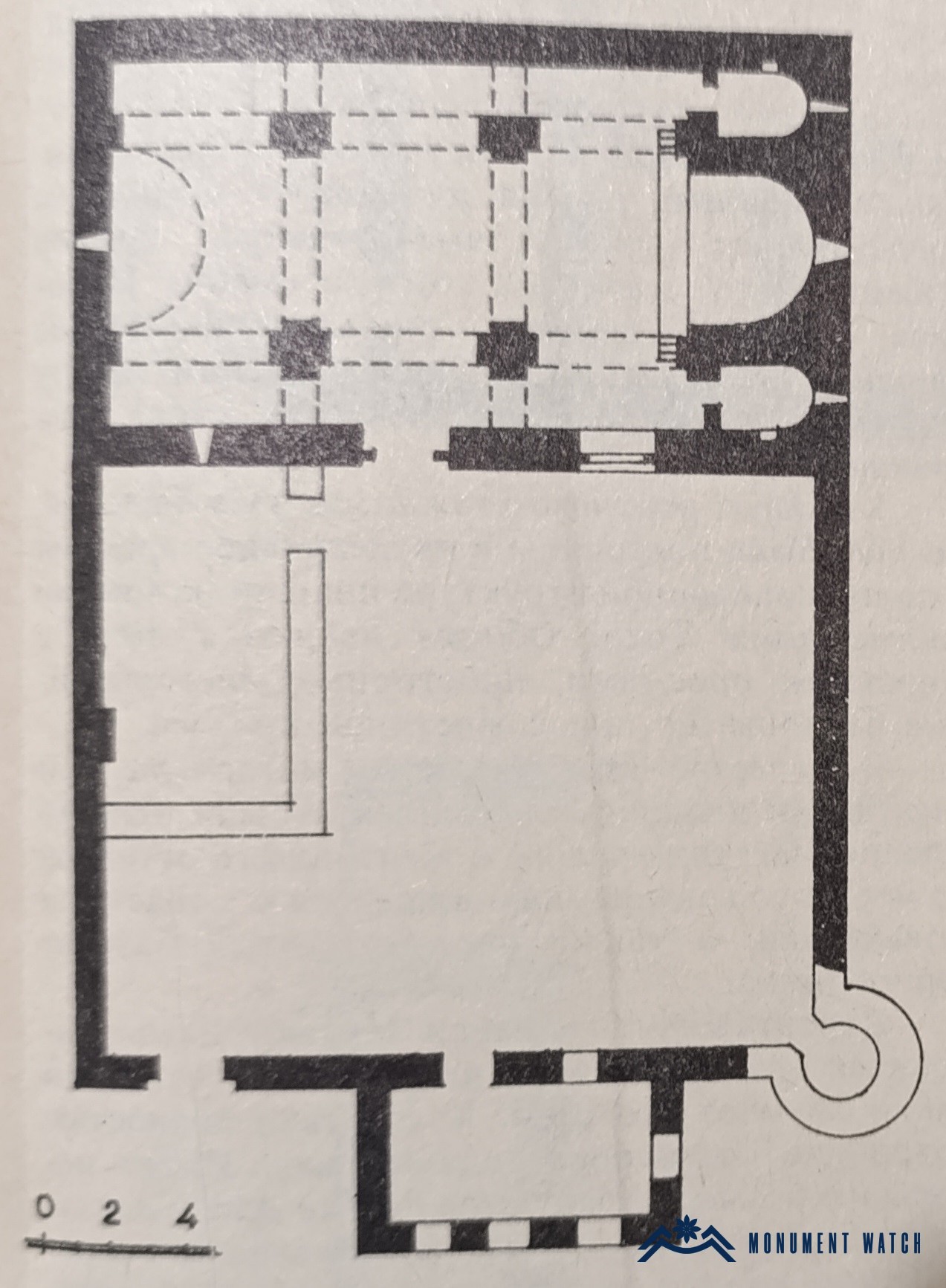

The church is in remarkably good condition. In plan and volume, it is a three-nave basilica. The two side aisles are relatively narrow, while the central prayer hall, which culminates in the tabernacle, is much broader. Each side aisle ends in a sacristy; each sacristy has a narrow window niche in both its south and north walls. Within the tabernacle, the raised platform (bema) stands above the main floor; two steps on each side reach it. In plan, the building's proportions are roughly 1 2, measuring approximately 12.9 × 21.7 meters.

There is only one entrance, located on the south façade, which opens into the enclosed courtyard. Light enters the prayer hall through narrow windows on the west wall and both narrow and more expansive windows on the south wall. The ceiling is a vaulted structure supported by ribs that rest on piers: on the south side, each dock has a cruciform base; on the north side, they rest on T-shaped bases. The roof above is a pitched (gable) framework covered with shingles. Initially, an octagonal rotunda–style bell tower rose from the ridge of that roof; this feature has since been reconstructed.

Structural elements are built mostly of semi-dressed tuff blocks. The door and window surrounds, as well as the corners of the walls, are composed of finely dressed ashlar. In several places within the wall faces, stones decorated with carved cross motifs are integrated into the masonry.

Immediately south of the church is a walled courtyard measuring about 17.0 × 22.0 meters. Historical accounts indicate that a small chapel–mausoleum once occupied this courtyard, serving as the burial place for the local ruling family. Archaeological excavations confirmed two additional adjoining structures within the courtyard—one to the northwest, likely used for practical purposes and a semicircular apsidal building to the northeast that contained multiple burial layers and probably functioned as the chapel–mausoleum mentioned in historical sources. More than eighty gravestones were uncovered during these excavations; some bear inscriptions identifying members of the ruling family, while others display sculptural ornamentation that reflects local artistic traditions.

Overall, these findings establish that the main church was constructed in the late 1600s or early 1700s. Two annexes were later built: one to the east (after 1729) and another to the west (after 1774/75). By the late nineteenth century, the southeastern annex had been partially covered with earth. It was used for additional burials, indicating its transition from a building to an informal burial ground.

A courtyard measuring approximately 17.0 × 22.0 meters lies immediately south of Surb Hovhannes Church (Fig. 6). According to Bishop Makarios Barkhudaryants, an oratory once stood within this courtyard and served as the mausoleum of the Dizakian–Yegan Melik family (Barkhudaryants 1895, 75–76). Excavations conducted in 2017 in the north and south yards confirmed these accounts (Yeranyan & Petrosyan 2022, 31–32).

Archaeological investigation revealed that within the courtyard's northeastern and northwestern sectors—inside the walled precinct—are the remains of two separate structures alongside roughly eighty gravestones. The northwestern building appears to have had an economic or ancillary function (Fig. 7). In contrast, the northeastern area contained a semi-circular apsidal structure, where burials from different periods were uncovered. This was likely the chapel–mausoleum mentioned in earlier sources.

Among the more than eighty gravestones discovered in the south yard, several bear relief carvings and inscriptions (Yeranyan & Petrosyan 2022, 38). Burials continued in this yard from the church's initial construction through the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Inscriptions on some of the stones identify members of the Melik-Yegan family interred here: Vardapet Ghukas (d. 1715), Melik Yegan (d. 1744), Melik Aram (d. 1745), Melik Yesayi (d. 1781), and Baghr Beg, son of Melik Aram (d. 1789) (Yeranyan & Petrosyan 2022, 36–38). The value of these gravestones extends beyond their inscriptions, which document historical persons and events, to their high artistic merit: the sculptural ornamentation offers insight into local cultural, creative, and ethnographic characteristics (Fig. 8).

Based on these excavation results, the constructive and chronological development of Surb Hovhannes Church and its adjacent buildings is outlined as follows: Between the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, the Surb Hovhannes Church was constructed. Subsequently, two annexes were erected: one to the east (after 1729) and another to the west (after 1774/75). By the late nineteenth to early twentieth centuries, the southeastern annex had been covered over with earth, serving later as a locus for secondary burials.

The Condition Before, During, and After the War

According to the inscription on the cross-stone, the last major renovation of Surb Hovhannes Church took place in the first half of the eighteenth century. During the Soviet era, the church underwent no significant alterations and remained largely intact. Following the First Artsakh War and the region's liberation, archaeological research and excavations became possible in 2017 (Yeranyan & Petrosyan 2022, p. 31). Beginning in 2018, restoration work was financed by Karen Safaryan, a native of Togh residing in Yerevan, under the direction of architect Manvel Sargsyan. The restoration included renovating the roof, re-crafting door and window surrounds, interior finishing, and site landscaping. The octagonal rotunda–belltower was also reconstructed. However, the original sculptural and inscription-bearing fragments were not re-incorporated into the new bell tower (Fig. 9). The church reopened in 2019.

In 2020, however, the entire complex was occupied by Azerbaijani forces. These forces, ignoring all historical evidence, have classified the church as Albanian and have denied its Armenian origins. By presidential decree, the historical Armenian village of Togh was renamed the Azerbaijani-Albanian "Tugh Sanctuary," effectively erasing its Armenian heritage ﹕https://syuniacyerkir.am/tokhi-surb-hovhannes-ekekhetsum-yntanum-en-verakangnman-ashkhatanqner.

Bibliography

- Barkhudaryants 1895 - Makar Bishop Barkhudaryants, Artsakh, "Aror" Printing House, Baku.

- CAE 5, Artsakh, compiled by S. Barkhudaryan, Armenian SSR Academy of Sciences Publishing, Yerevan, 1982.

- Yeranyan, Petrosyan 2022 - Yeranyan N., Petrosyan H., “Main Results of the Archaeological Research of Surb Hovhannes Church in Togh,” Works of the History Museum of Armenia No. 2 (10), Yerevan.

- Mkrtchyan 1985 - Mkrtchyan Sh., Historic-Architectural Monuments of Nagorno-Karabakh, "Hayastan" Publishing House, Yerevan.

- “Restoration Works Are Ongoing at Surb Hovhannes Church in Togh” https://syuniacyerkir.am/tokhi-surb-hovhannes-ekekhetsum-yntanum-en-verakangnman-ashkhatanqner.

The Surb Hovhannes Church Complex in Togh

Artsakh