Dadivank. About Saint Dadi and his grave

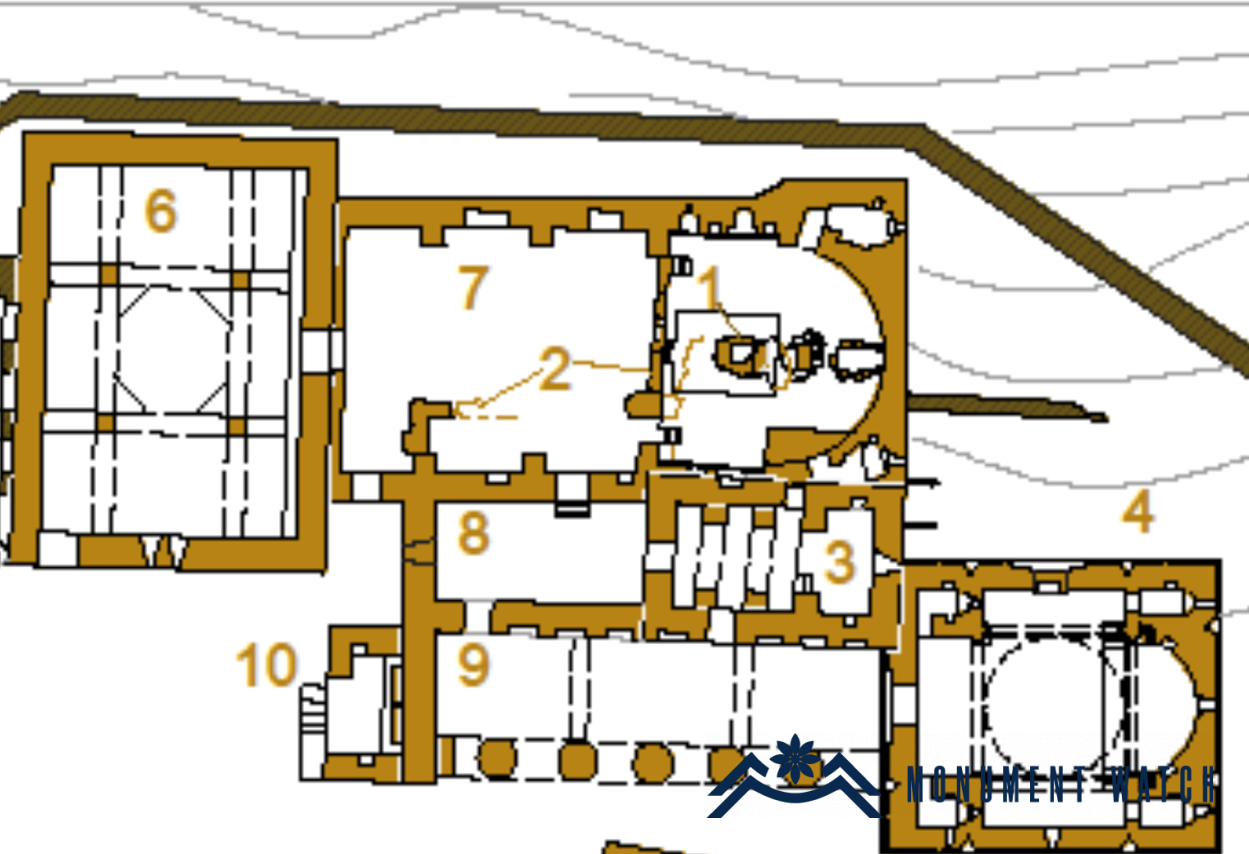

Dadivank's current structures are not older than the 12th century. This monastery's history is essentially a story about the Upper Khachen princely house and its spiritual activities. Excavations in Dadivank have revealed the remains of an ancient megalithic structure (whose circular burial pit constructed with tiny, irregular stones resembles a pre-Christian burial chamber) and the remains of a chapel built on it. At the end of the thirteenth century, an attempt was made to construct a large church that would include the chapel beneath the bema. However, for some reason, it was never completed. A single-nave church with a rectangular tabernacle was constructed on the southern side of this chapel, facing east, before the middle of the 12th century, and a rectangular hall-courtyard was built adjoining it from the west. The main church of Dadivank, which was built in 1214 according to the inscription, is also attached to the single-nave church with its northwestern corner (Fig. 1).

About Saint Dadi

The first written source about Saint Dadi and Dadivank is found in Movses Daskhurantsi's 10th-century work "History of Aghvank," which concerns 9th-century events: "Varaz Trdat and his son Stephanos Nerseh Philippean, as well as a relative, were murdered in Khoradzor, known as Dado monastery" (Kaghankatvatsi 1983, 340).

Mkhitar Gosh has provided the next bibliographic information (end of the 12th century). When describing the raids of the Choli amira on Artsakh during the battles for Gandzak in 1145, he mentions the destruction of the Dadu monastery: "The apostolic holy place known as Dadivank" (Kaghankatvatsi 1983, 353). Mkhitar Gosh makes no mention of why the monastery is apostolic or who Dadu is. It can only be hypothesized that the monastery's apostolic origin was already known. In addition, the author has stated on the same page that even though Choli destroyed and captured Artsakh's fortifications a year ago, he had to attack and raid again: "...on the side of Khachin, Tandzeats, and Adakh, because not a single castle remained in his hands during the previous advance, but was liberated from him, those who had fled to cedrus forests, took their swords and fortresses from them and rebelled against Turks" (Kaghankatvatsi 1983, 353).

Around this time (the early 1140s), Hasan Vakhtangyan, the elder lord of Khachen, begins his liberation struggle, which he describes in the inscription of the khachkar he constructed in Dadivank in 1182: "I, the son of Hasan Vakhtang, the lord of Haterk and Handaberd, Khachinaberd and Havakhrats, have been in seniority for 40 years. With the help of God, [survived] many wars and defeated my enemies. I gave birth to 6 sons and inherited them my fortresses and province, and came to this monastery. To Father Grigor I became a priest, and brought the khachkar of mine Aghuay, elaborately worked, and with many efforts raised it to commemorate the Holy Cross (Surb Nshan) and my soul. Thus, for the sake of your souls, you who read, remember my prayers. In the year 1182" (CAE 5, 198). We can see that the monastery is mentioned in this inscription without specifying its name.

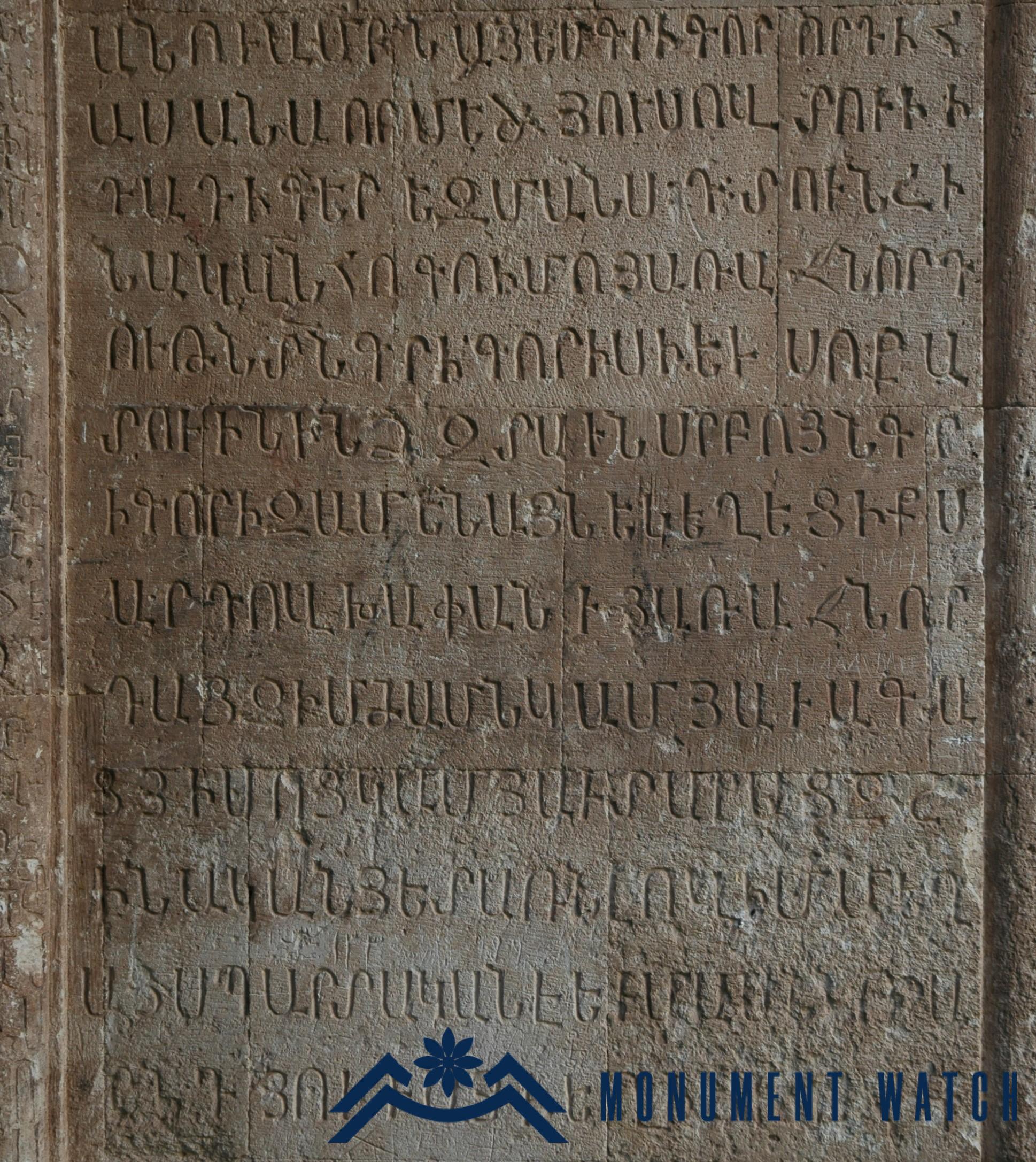

Further information is available about the end of the 12th century and the first half of the 13th century when Armenian princely houses liberated their estates from Seljuk rulers with the help of joint Armenian-Georgian forces. This liberation struggle was regarded as a holy war, and the rapidly growing powerful princely houses replaced local saints with pan-Armenian or general Christian saints (Petrosyan 2017, 236-237). The Zakarians made St. Sargis the patron saint of the liberation struggle (especially given his powerful character and the fact that their father was also named Sargis), the Hasan-Jalalyans - Stepanos Nahavka, and Hovhannes the Baptist. Based on the similarity of his name to Saint Thaddeus-Thadeous and possibly some other local legends, the owners of Upper Khachen or Haterk recreated the image of Dado or Dade. It is worth noting that the monastery is referred to as "Dadi's grave" in an inscription carved on the wall of the monastery's main church in 1224 by the Lord of Upper Khachen and Tsar, son of Hassan and Dop: Grigor. The inscription says "in the year 1224. I, father Grigoris, superior of this holy convent, son of Vasak, the martyr, created this chapel for the commemoration of my soul and prayers." (CAE 5, 201, Fig. 2)

Vardan Areveltsi introduces this passage in his translation of Mikael Asori's chronicle from the middle of the 13th century: “Some Thaddeus, from the pagans, who went to Greater Armenia and the northern lands by the commission of Thaddeus (Apostle), and upon hearing about the death of Abgar, turned and moved to Smaller Syunik and was murdered for secret preaching. The monastery was built in that place and named after him” (Asori 1871, appendix 33; Vardan likely obtained this passage from his teacher monastic vardapet (monk), where the saint is referred to as Dadiu, as it is with Mkhitar Gosh; cf. Alishan 1902, 22-23, Matevosyan 2020, 26-28). As a result, attempts were made to change the saint's name to match that of Saint Thaddeus as additional "proof" of his apostolic origin. It can be concluded that Mkhitar Gosh and monastic vardapet (monk) breathed new life into local traditions about Saint Dadi and his grave, justifying and strengthening his image as the patron saint of the Upper Khachen princely house as a pan-Christian saint.

Grave and Chapel of Saint Dadi

There is no clear structure or tomb to indicate Dadi's grave in early 19th-century descriptions and surveys. The great basilica of the north was a possible location for it, potentially because of its unusual width (which could be reminiscent of similar early Christian temples) and the extraordinarily large column constructed in the apse (which could be reminiscent of early Christian monuments, such as were also built on the tombs of saints).

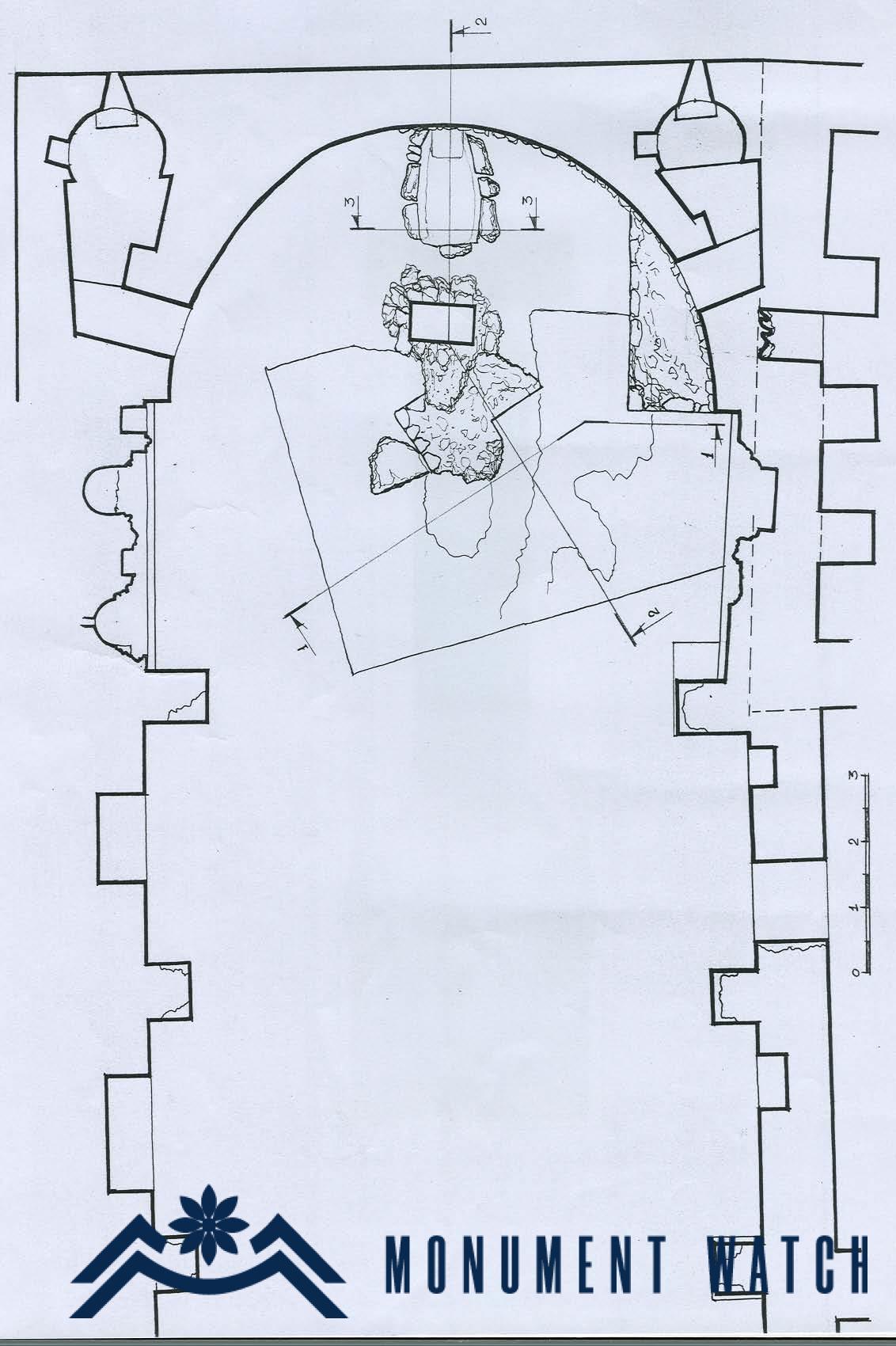

Modern research, however, indicates that the current structure of the basilica church dates from the late 13th century and was built by the monastery's abbot, Bishop Athanas. The same can be said of the monument standing on the stage (Fig. 4), which is close to the anchors of the church's pillars in terms of dimensional resolution and processing. However cross sculptures and an inscription representing the year (possibly 1361 or 1370), most likely refer to the 13-14th centuries. It is also important to note that the earlier small basilica church adjoining this basilica to the south, as well as the main church a bit further to the southeast (built-in 1214, i.e. earlier than the current building of the great basilica), have north entrances. It is a well-known fact that Armenian churches had a northern entrance only in rare circumstances, such as when it was not technically possible to open the entrance from the west or south, or when there were special ritual or religious cases. Since the technical aspect is excluded in this case (the small basilica also has an entrance from the south and the main church one from the west), the presence of the northern entrances must be related to the existence of some sacred place in the area of the large basilica, in this case, a grave attributed to Saint Dadi (cf. Ayvazyan 2015)., 52-53). It is reasonable to assume that when Vardapet Athanas began work on the new church, he had already removed the valuable relics from the ruined tomb and chapel to place them in the new structure. This is demonstrated by the proscenium, which is a unique manifestation of Armenian Church architecture, as well as the numerous sculpted niches incorporated into the walls (Fig. 3).

The ruins of the grave were hidden beneath the church's proscenium and stage. It is worth noting that S. Ayvazyan, the restoring architect of Dadivank claims that Athanas did not initiate a church and abandoned it, but instead created a unique inner courtyard around Dadi's grave and chapel (Ayvazyan 2015, 56). This point of view, however, leaves unsolved the question of how that inner courtyard came to be formed if neither the tomb nor the chapel was visible or accessible.

Indeed, as the excavations revealed, the burial pit was lined with small rough stones, and the chapel built on it was incorporated into the church's proscenium and stage (Figs. 4, 5). Excavations uncovered the remains of a wooden palanquin (Fig. 6), an onyx wand head, and human bones dating from the mid-12th century (the first phase of excavations was conducted by Hamlet Petrosyan, see Petrosyan 2007, the second phase by Gagik Sargsyan, architect: Samvel Ayvazyan, see Ayvazyan, Sargsyan 2012, 1-11, Ayvazyan 2015, 68-73). Thus, at the end of the 13th century, Vardapet Athanas incorporated the already dilapidated structures beneath the stage and proscenium of the new church and carved several sculptured niches in the proscenium's walls for the separated relics. Father Athanas did not complete the church's construction, so it remained an open-air structure.

Bibliography

- Alishan 1902 - Alishan G., Daybreak of Armenian Christianity, Venice, St. Lazarus.

- Ayvazyan 2015 - Ayvazyan S., Restoration of Dadi Monastery in 1997–2011, Yerevan, RAA publication.

- Ayvazyan, Sargsyan 2012 - Ayvazyan S., Sargsyan G., Excavations in Dadivank in 2008, VARDZK No. 7, pp. 1–11.

- Asori 1871 - Chronology of Ter Michael, Patriarch of Assyria, Jerusalem.

- CAE, 5-Corpus of Armenian Epigraphy, issue 5, Artsakh/ made by S. Barkhudaryan, Publishing House of the USSR Academy of Sciences of RA, Yerevan, 1982.

- Kaghankatvatsi 1983 - Movses Kaghankatvatsi, History of the country Aghvank, Publishing House of the USSR Academy of Sciences of RA, Yerevan.

- Matevosyan 2018 - Matevosyan K., Dadivank and its murals, Dadivank. A Reborn Wonder, Yerevan, pp. 25–40.

- Petrosyan 2007—Petrosyan H., in the apse section of the great basilica church of Dadivank in 2007. Preliminary report of the exploratory excavations carried out in July, the archive of the Foundation for the Study of Armenian Architecture.

- Petrosyan 2017 - Petrosyan H., Excavations of the Surb Stepanos Monastery in Vachar and the issue of modernization of all-Christian saints and relics in the 13th century, Armenia and the Eastern Christian civilization, International conference reports and provisions of the reports, Yerevan, "Giyutyun" publishing house, pp. 231-237.

Dadivank. About Saint Dadi and his grave

Artsakh