The Ine Mas Anapat (Desert of the Nine Relics)

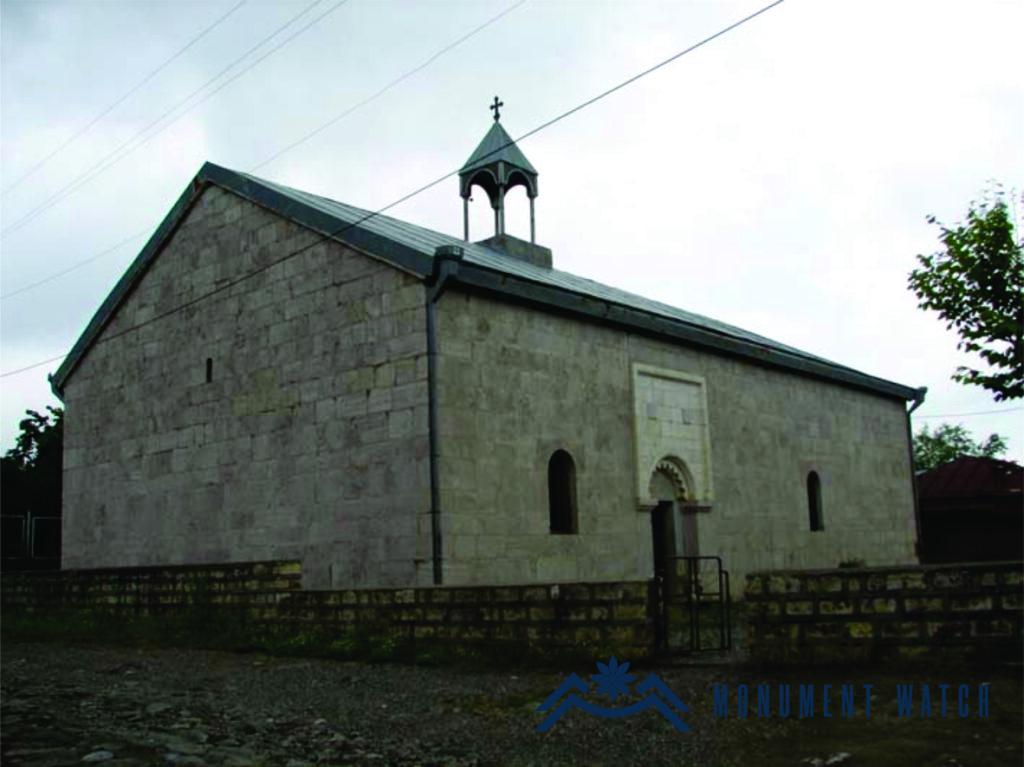

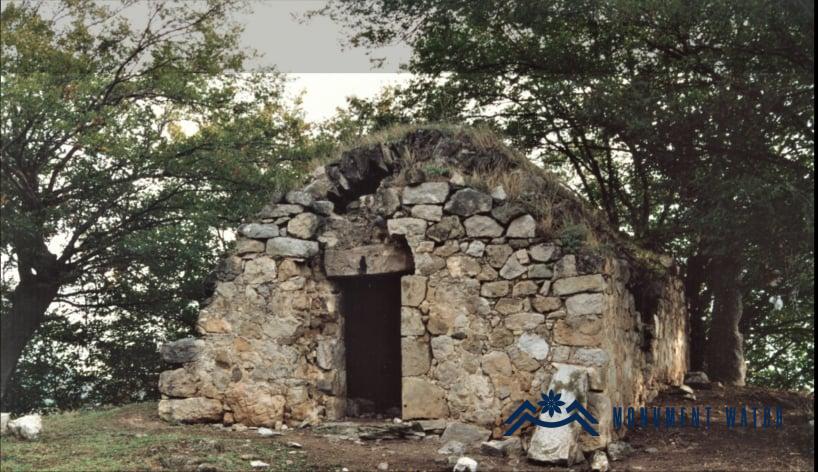

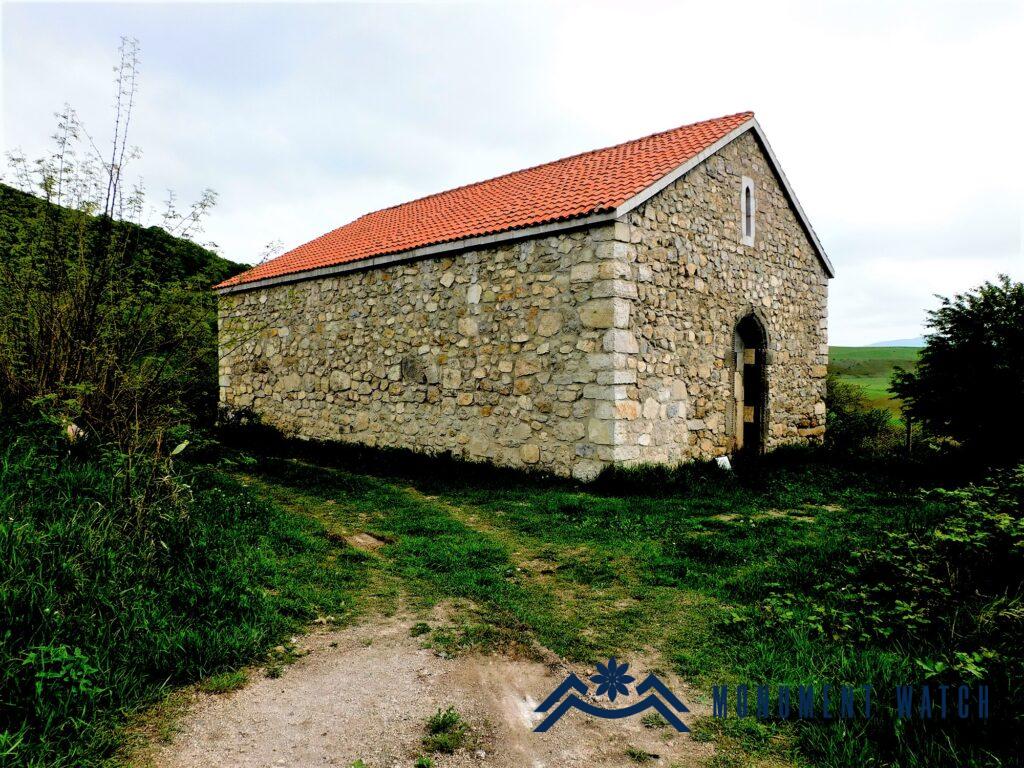

Location The Ine Mas Anapat is situated on the namesake plateau, stretching between the villages of Kusapat and Mokhratagh in the Martakert region of the Republic of Artsakh. Positioned 500 meters east of the Old Mokhratagh village, the monument group rests atop a hill surrounded by mountains, dense forests, and streams meandering through the landscape. This natural setting has served as a protective barrier for the monastery. The current church, known as Ine Masants or Anapat (Fig. 1), is situated on the southern edge of the village, close to the mouth of the valley, where remnants of other religious structures are also discernible (CAE 5, 93). The complex is currently under Azerbaijani occupation. Historical overview The old village of Mokhratagh was historically significant, once serving as a large settlement and a residence for Meliks, with a population of up to 700 houses. Only limited historical information about the village and the surrounding area has been preserved. Makar Barkhudaryants provides some details, mentioning the location of the residence, the church that remains there, the estate of the Melik Israelyans, and the cemetery associated with the princely house. The author also notes that at the time of his visit, the village was already abandoned, and the inhabitants had relocated to Nor (New) Mokhratagh (Barkhutareants 1895, 216, 217). Jalalyants mentions two churches (Inne masants, Astvatsatsin) and a mansion belonging to Melik Adam in Old Ashram (referred to as the Small Village) (Jalalyants 1842, 180). According to them, the Ine Mas Anapat was a favorite place of pilgrimage for the locals and residents of the surrounding villages. There is no information about the origin of the name of the complex; it is only assumed that it got its name due to the nine relics kept there. Architectural-compositional examination The Ine Mas Anapat was a complex of buildings of various types and natures. Currently, the primary church, gavit walls, tombstones, over two dozen inscriptions, and other monumental structures remain intact. It is believed that there was a church on the site as early as the 12th century, which is supported by the presence of khachkars from the 12th and 13th centuries embedded in the walls of the main church. The current church was constructed in the late 19th century. Three inscriptions within the building provide information about its construction. The first inscription is located on the northern wall and reads, “The Holy Temple of Ine Masants was built in 1881 with the donations of the people under the Vardapet Hovsep Pinachyants” (Barkhutareants 1895, 217). The second inscription is on the left side of the main tabernacle, on the southern edge of the pilaster. It reads, “The Ine Masants was built as a gift from Sharkhanum in the name of the soul of Harutyun-bek Atabekyan, the village of Kusapat, 1884” (Barkhutareants 1895, 217). Lastly, there is an inscription on the lintel above the entrance (Kerobyan 1984, 238) (Fig. 2). The current church has a rectangular layout, measuring 8.0 by 13.0 meters externally (Fig. 3). It was built with roughly polished and rough stones, predominately limestone, but also sandstone and river stones were used. The corners, niches, and arches of the church walls, along with the frames of the openings were constructed using cut limestone. This type of construction is also found in the architectural complexes of Syunik, adjacent to Artsakh. The buildings were primarily constructed using rough-polished stones, while regularly shaped polished stones were reserved for corners, arches, domes of the conch, drums, and other structurally critical areas (Hasratyan 1973, 151). The only entrance is situated at the southern corner of the western wall of the church, deviating from the longitudinal axis. Next to the entrance on this side, there is also a window.