“Kronk” cave monastery of Tsakhkaberd

Location

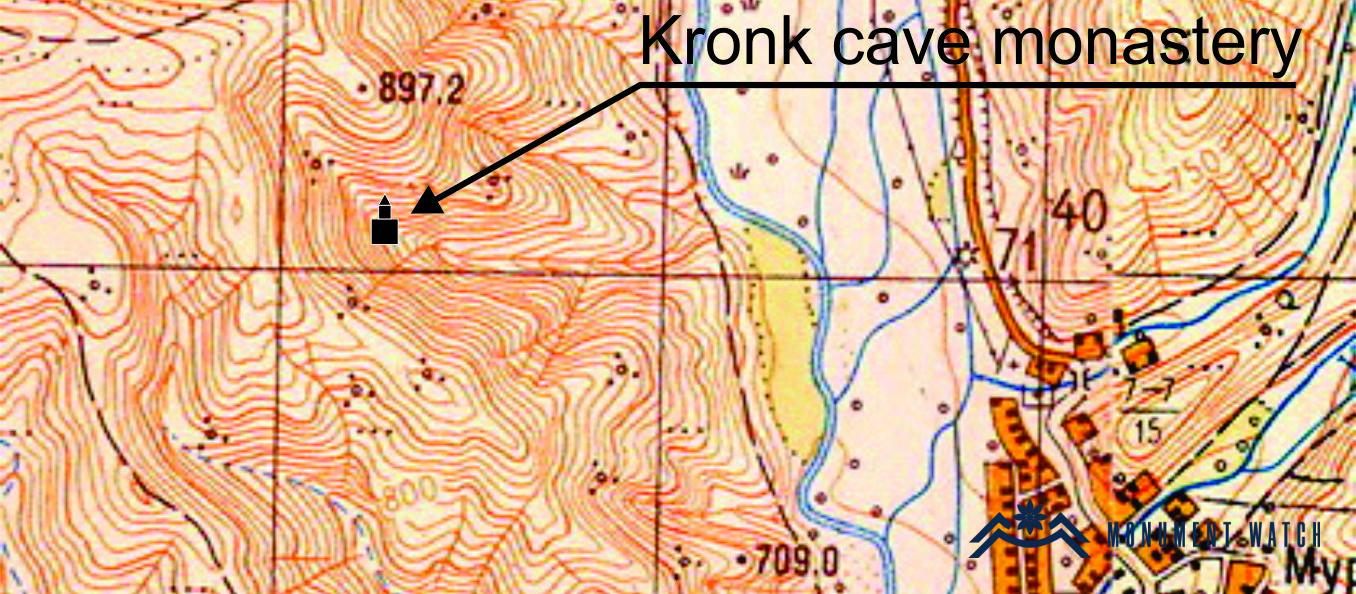

The "Kronk" monastery is about 3 kilometers southwest of Tsaghkaberd in the Kashatagh region, in one of the rocky ravines on the right side of the Hakari river, about 1-2 kilometers from the river (fig. 1). Following the second Artsakh war, those territories and the monastery were retaken by Azerbaijan.

Researchers discovered several rock-hewn churches in the Kashatagh region, which was liberated after the first Artsakh war. The caves in the river gorges were formerly private and safe sanctuaries, far from the invaders. The majority of the cave churches were initially hermitages.

Fig. 1 The general view of the "Kronk" Cave monastery, photo by S. Danielyan.

Historical overview

Stephen Orbelian, a 13th century historian, mentions the "Kronk" monastery (Stephen Orbelian 1986, 282). The settlement of Krvank in the 7th province of Haband is referenced in the 74th chapter of his historical record, "Tax list of the twelve provinces of Syunik according to the old regulations," with a tax amount of 20 parts (given to the Tatev monastery), where possibly the "Kronk" monastery was located (Stephen Orbelian 1986, 400).

Architectural-compositional examination

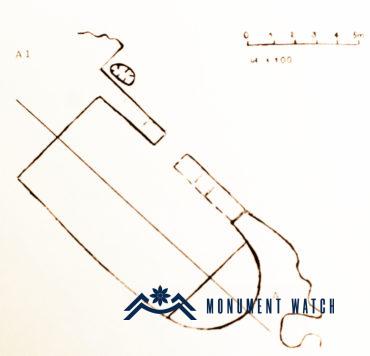

Kronk is a cave monastery complex carved into a rocky gorge. Due to their softness, the vertical white limestone rocks easily cave in. Only a part of the complex has been maintained today. The church is built on the cliffs at the gorge's southern end. On the northern edge of the cliffs, there are several anthropogenic cave exits. Rooms are hewn on four levels on this side, joined by nearly impenetrable tunnels that, in some areas, develop into nearly vertical holes (fig. 2). These caves were once used as shelters, and the holes inside were most likely used for storage. It is possible to enter one of them and climb up through the other. In addition to the preserved room, the sanctuary featured a second room. This is evidenced by the holes meant for the wooden roof logs. The basement floor was also maintained, although the entrance was partially blocked, making it impossible to descend.

Fig. 2 The main architectural plan of the "Kronk" complex, Shahinyan S., Sacred Underground Structures of the Gochants River Basin, Cave Structures of Mountainous Armenia-Artsakh, NUASA, Yerevan, page 45.

The complex includes a rock-hewn church, although it is separate. On the layout, it is a basilica-style structure stretched longitudinally (fig. 3). It is 12 meters in length, 8 meters wide, and 5 meters high. The northern longitudinal wall has two windows. The interior walls and facade have been smoothed out (fig. 4).

The church is in a state of extreme emergency. On the northeast side, the entrance and a portion of the window have already collapsed. The entry wall is over 1.5 meters thick, yet it has already broken in several spots and is unsupported (fig. 5). The northern section of the tabernacle has been destroyed, as has the stage; only the remnants of stairs remain on the side of the intact wall. The preserved wall has two niches, which were most likely crosses that have been demolished.

By construction, the "Kronk" church is partially rock-hewn and partly above-ground. This type of architectural tradition is common in the Armenian highlands. The Geghardavank complex contains similar solutions (Harutyunyan 1996, 301-308). The presence of various cave buildings hewn into the rocks around the church, which were the residences of the church servants and also functioned as hiding places, adds to the complex's similarity (Shahinyan 2020, 44).

Fig. 3 The architectural plan of the complex's church, Shahinyan S., Sacred Underground Structures of the Gochants River Basin Cave Structures of Mountainous Armenia-Artsakh, NUASA, Yerevan, page 48.

Fig. 4 The facade of the monastery-church, photo by S. Danielyan.

Fig. 5 The interior of the church, photo by S. Danielyan.

Bibliographic examination

As early as 1987–89, research on rock-hewn complexes was conducted in the Kashatagh region. The research was carried out by the speleological expedition of the Armenian SSR's NAS institute of geography.

These works were put on hold due to the escalation of the Artsakh conflict, but they were resumed in 2003. The Speleological Center of Armenia conducted the research. The collaborative research studies of the latter and international scientific expeditions on speleology in the Hakari River basin and its tributaries were summarized in local and worldwide scientific journals and magazines (Shahinyan 2015, 164–168). The architectural plan and a full description of the "Kronk" monastery are included in the collection of international conference materials (Gunko, Shahinyan, Kondrateva 2021, 57–63).

Samvel Karapetyan writes in his book "Monuments of Armenian Culture in the Occupied Territories of Soviet Azerbaijan" about St. Astsvatsin Church of Anapatik Village, which is referenced in the manuscript "Exegesis of Liturgy," created in 1361, and quotes this passage: "This was written as a sign of devotion to St. Mary by the liturgical exegetic, Zaqaria Hieoromonk, in the gorge of Haykara, near the village of Anapatik, during the Khanate of Yois and the reign of St. Stephanos Catholicos. It was the year 810.” (Karapetyan 1999, 185).

Since the rock-hewn churches are commonly referred to as Anapats, it is reasonable to believe that the "Kronk" sanctuary is the Anapat mentioned above.

The condition before, during, and after the war

Tsaghkaberd was known as Gulyberd during the Soviet era, and it was the last village in the Lachin region to the south, bordering Goris. The community was depopulated and inhabited by Muslims during that time. The village's "Kronk" sanctuary and the stone-built houses surrounding it were primarily used as cow barns. During this time, the complex's entrance to the church was exploded. Kronkavank once again served as a Christian sanctuary following the first Artsakh war and the liberation of the Kashatagh region.

It did not change significantly during or after the Second Artsakh War.

Bibliography

- Karapetyan, 1999-Kapetyan, S., Monuments of Armenian Culture in the Occupied Territories of Soviet Azerbaijan, "Science" Publishing House of NAS RA, Yerevan.

- Harutyunyan 1992-V. Harutyunyan, History of Armenian Architecture, "Luys" State Publishing House, Yerevan.

- Stephen Orbelian,1986-Stephen Orbelian, History of Syunik, Translation, introduction and notes by A. Abrahamyan, "Soviet Writer" publishing house, Yerevan.

- Shahinyan 2015 - Shahinyan S., Religious Underground Structures in Gochants Basin (Artsakh), Speleology and spelestogy: Proceedings of the VI International Scientific Conference.-NGPU, Naberezhnye Chelny, 164-168.

- Shahinyan 2020-Shahinyan S., Sacred underground structures of the Gochants river basin: Cave structures of mountainous Armenia-Artsakh, NUASA, Yerevan, 44.

“Kronk” cave monastery of Tsakhkaberd

Artsakh