The khachkars and tombstones of Gandzasar

In Armenian monastic structures, khachkars and tombstones have a special significance. These diminutive monuments not only attract with their architectural designs, sculptures, and locations but also offer insightful information through their inscriptions, revealing astonishing details about the linked monasteries and princely houses. The monuments of Gandzasar are extraordinarily valuable in this sense.

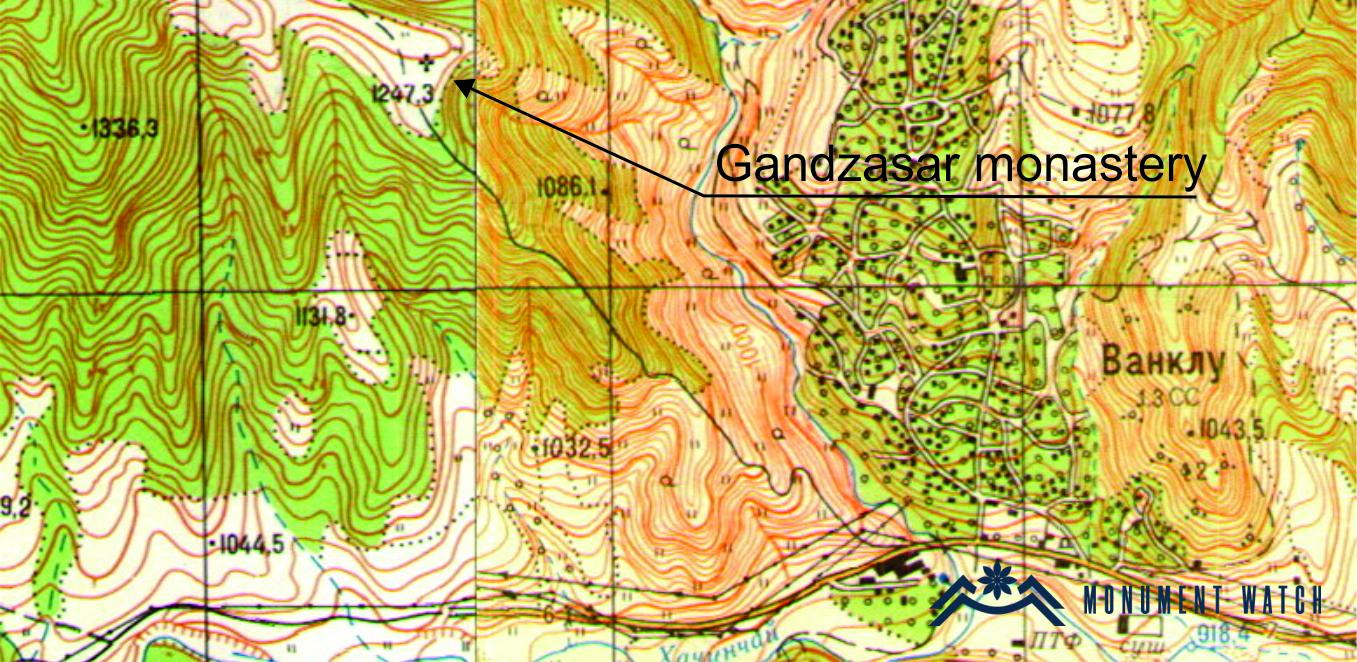

As mentioned earlier (The Monastery of Gandzasar: general information - Monument Watch), Gandzasar Monastery has been a dynastic cemetery for the Khachen princely house since the 12th century. Therefore, it is not surprising to find khachkars and tombstones here that predate the existing structures in the area. Equally noteworthy are the khachkars collected in the monastery's courtyard from various nearby locations, a common practice seen in many monastic complexes (Fig. 1).

One notable artifact preserved within the Gandzasar monastery is a limestone slab (Fig. 2). This slab features a quadrangular tabernacle adorned with simple ribbon knitting. The cross, although now faintly visible, stands on a stepped plinth. It displays a sturdy and compact form with thick, braided arms, each terminating in two octagonal rosette buttons. On the cross-section, similar rosette ornamentation is visible. A striking feature of the board is the presence of a through-hole and a protrusion with saw-shaped battlements on the interior, although a part of it appears to be damaged or broken. This distinctive feature may have significance related to the board's intended purpose or its overall shape. On the reverse side of the board, there is an engraved inscription (Fig. 3) that likely demonstrates the work of three distinct scribes, who created their inscriptions at different times. The section providing the composition's creation date is inscribed using a regular majuscule script, with the letters evenly spaced and aligned along regularly formed lines; "In the year 916 of the Armenian calendar, may God offer his congratulations." The inscription likely does not refer to the crucifix itself but, based on the phrase "May God offer his congratulations," it is likely referring to a device or object of which the crucifix was a part.

In addition to the two early khachkars (Fig. 4), Gandzasar Monastery also houses a collection of more classical khachkars dating back to the 12th and 13th centuries. These khachkars exhibit sculpted cornices and edgings, featuring a central woven cross and bird adornments emerging from the base (Figs. 5, 6). Notably, several khachkar inscriptions depict the successors of the Khachen princely house and their relatives, which hold special significance (for a detailed analysis, refer to Ulubabyan 1975, 135–143 and Hakobyan 2020, 295-297, 311-314).

Among the notable khachkars at Gandzasar are those raised by Princess Nrjis in memory of Prince Vakhtang in 1174. One of these khachkars portrays Prince Vakhtang as a mounted warrior. Additionally, there is a khachkar raised by Hassan the Great in 1181 (Fig. 7), which depicts the late wife of the deceased prince, whose name was Taguhi, and their daughter, Khatun. The sculpture shows the mother holding her young daughter in her arms while seated on a throne. In front of them, a table covered with food is depicted (Figs. 8, 9).

Regarding the sculpture of Prince Vakhtang, it is worth noting that in the khachkar sculptures of Artsakh, reaching hundreds in number and including those found in Gandzasar, there is a consistent depiction of horses in a majestic and dynamic pose. The reins and details of the bridle, such as the triggers, are often depicted with precision. The horse's tail is typically shown knotted, with an oval or elongated pendant hanging from the neck. The saddle, although usually not visible under the rider, can be inferred from the presence of a collar and a strap passing under the tail. Occasionally, the stirrups can be seen hanging from the saddle. Only the head is facing forward while the rider is seated in a serious upright stance with his entire body visible from the side. The helmet hat is used to distinguish it from the costume, which frequently has a sharp, occasionally diamond-shaped protrusion at the end. From the helmet’s lower border to the shoulders, two braids fall. In other instances, it is obvious that they are not actual braids but rather a component of the helmet. Some sculptures depict a belt that is around mid-width, usually supported by two seals, from which a long sword hangs. A wide chokha that hung below the knee was worn by warriors. Typically, the rider uses one hand to wield the lance and the other to grasp the bridle. The lance has a diagonal blade at the end and is longer than the horse. The bow, quiver, long sword, shield, mace, and other symbols are also included. Afoot soldiers are armed with a sword or a bow and arrow, unlike riders. On occasion, there will be images of three afoot soldiers or even two horsemen. These soldiers are mentioned in Akhundov's subsequent "discovery," which suggests that the khachkars of Artsakh, Utik, and Jugha have Albanian origins. Having limited knowledge of the subject matter based solely on the photograph of the 1174 khachkar at Gandzasar, he swaggers and asserts that "Albanian" khachkars can feature depictions of foreign, and even Mongolian, warriors (Akhundov 1986, 244-245). However, this "discovery" is flawed, particularly in the assumption that the presence of "braids" is exclusive to Mongols. It appears that the Azerbaijani "appropriator" became fixated on the notion of "braids" as a Mongolian characteristic, overlooking the significant detail of the warrior's long lance, which is not at all indicative of Mongols. The primary weapon of the Mongols was the bow and arrow, which is why the Armenians referred to them as "throwers" or bowmen. Grigor Akanetsi, a historical figure who lived near Gandzasar in the Akana fortress and documented the Mongol conquest of Transcaucasia, specifically Artsakh, titled his book "History of the Throwers' (Bowman) Nation" (Akanetsi 1961). However, it is important to note that depictions of warriors with "braids" have been observed on khachkars in Artsakh since the 11th century. The presence of such sculptures is evident in khachkars dating back to various years, including 1158, 1174, 1180, 1181, 1183, 1186, 1189, 1194, 1203, 1205, 1212, and 1215. It is worth mentioning that during this time, the Mongols were not only absent from the region but were also unknown in the Middle East. Regarding the depiction of long-haired warriors with "braids," it is important to note that they were not uncommon in Armenian military and cultural contexts. In a comprehensive study (Petrosyan 2001, 75-81), it was demonstrated that such warriors were part of a distinct class of young warriors referred to as "Manuk (children)" in Armenian sources. R. Geushev is also an expert at manipulating or "ignoring" facts. He presents the khachkars of the Tsovategh archaeological site in Chankatagh village of Artsakh (a significant portion of which he once stole and took to Baku) as materials from the Skhnakh archaeological site of Caucasian Albania, "not remembering" the recorded and numbered examples in Armenian, and declaring that, unlike neighboring countries, human figures are one of Caucasian Albania's distinguishing features (Geushev 1984, 102-103).

The walls of the Gandzasar monastery's constructions feature diverse and unique cross compositions, adding an intriguing touch to the otherwise uniform surfaces. These compositions are created by pilgrims and depict individual believers, with some of them even bearing the names of the individuals who commissioned them (Fig. 10).

A Special mention should be given to Mr. Velidjan and Grigoris the Catholicos, who raised two remarkable khachkars in the monastery gavit in 1507 and 1563, respectively (Fig. 11). These khachkars stand out for their intricate sculptures and extensive inscriptions. One of the khachkars depicts Mehrab, the father of the Catholicos, riding on horseback and wielding a spear adorned with a cross. He is accompanied by a cupbearer carrying a jug and a cup (Fig. 12).

The eastern part of the Gandzasar gavit hall houses the preserved tombstones of notable individuals, including Prince Hasan-Jalal 3rd, who lived in the 15th century, several Catholicos figures, Metropolitan Baghdasar, and other secular individuals (Fig. 13). The marble gravestone of Prince Jalal III (Ulubabyan 1975, 305-307) is an exceptional piece, known for its distinctive sculptures (Figs. 14, 15, 16, 17). The inscription on the gravestone reads, "This is the grave of Jalal the Great. Remember in your prayers, the year 1431". The composition of the gravestone, particularly the sculpture of the six-pointed star symbolizing the Morning Star (Fig. 16), has been subject to different and sometimes fantastical interpretations. On the gravestone, three rosettes symbolize the sun, moon, and morning star, representing the expectation of the Second Coming and the salvation of departed souls (Petrosyan, Yeranyan 2022, 51). This composition, featuring three celestial bodies adorned with various decorations, can be traced back to the 5th to 7th centuries. Originally, these symbols were directly depicted on the walls, particularly on the lintels and crowns of church windows. Subsequently, they became a prominent element in the design of khachkars, appearing from the 9th century onwards and continuing to be used on tombstones during the 12th to 13th centuries, until the 19th century.

In conclusion, it is worth noting the tombstone of Anna Aslanbekyan, a native of Tbilisi who passed away in Khankend (now Stepanakert). This tombstone features inscriptions in both Armenian and Russian, as well as sculptures of angels floating in the sky (Fig. 18). This unique design element has been adopted as the logo for our website, Monument Watch (https://monumentwatch.org/).

Bibliography

- Akanetsi 1961- Grigor Akanetsi, History of the Throwers' (Bowmen) Nation, Armenian original and Georgian translation by N. Shoshianshvili, Tbilisi.

- Petrosyan 2001 - Petrosyan H., The figure of "Manuk" in late medieval Armenian tombstone sculptures (15-17th centuries), Tukh manuk, Yerevan, pp. 68-84.

- Petrosyan, Yeranyan 2022 - Petrosyan H., Yeranyan N., Monumental Culture of Artsakh, Antares, Yerevan.

- Ulubabyan 1975 - Ulubabyan B., Khachen's rule in the 10th–16th centuries, Publishing House of the USSR Academy of Sciences, Yerevan.

- Akhundov 1986 - Akhundov D., Architecture of Ancient and Early Medieval Azerbaijan, Baku.

- Geushev 1984 - Geushev R., Christianity in Caucasian Albania, Baku.

The khachkars and tombstones of Gandzasar

Artsakh