The Yerits Mankants monastery

Location

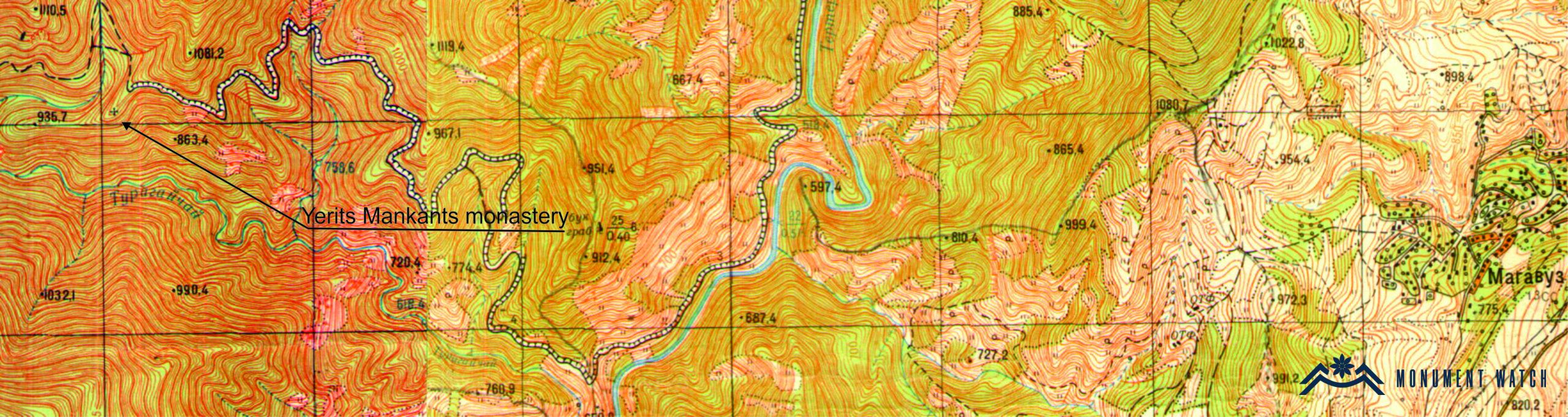

The Yerits Mankants Monastery is situated in the Martakert region of the Republic of Artsakh (Nagorno-Karabakh), precisely 5.0 kilometers from the historic Jraberd. It graces the slope of one of the southern extensions of the Mrav mountain range, which is cloaked in pristine forests, on the left bank of the Trghi River. Just above the monastery complex, nearby, lies the nearly deserted village known as Khotorashen (also referred to as Khokhomashen). Below the monastery rests Jraberd. The entire complex is ensconced amidst towering mountains, with the road leading to the monastery traversing a densely wooded terrain, rendering the passage somewhat challenging (Fig. 1).

Historical overview

Historical sources indicate that the Yerits Mankants Monastery complex was constructed with the specific intention of disrupting the cohesion of the Catholicosate of Aghvan, which was centered on the Gandzasar monastery.

The southern entrance of the monastery bears an inscription on its facade that provides information regarding the construction of the monastery church. "In the era of the illustrious Persian monarch, Shah Suleiman I, Simeon, the Catholicos hailing from Aghvan, who, by the divine grace, oversaw the construction of this church. Alongside me stood my brother, the revered Ignatios, both born of the lineage of Priest Sargis Metsashents. O descendants of Sion, as you pass through the hallowed threshold of the Lord's door, remember me in your prayers to Christ” (CAE 5, 96-97). The inscription bears witness to the fact that this complex was funded under the patronage of the Persian Shah and came into existence in the year 1691. Its construction was masterminded by Simeon, the offspring of Priest Sargis from the village of Mets Shen in the Jraberd province. Simeon, who traces his lineage back to the esteemed Catholicos from Aghvan, reigning until 1705, spearheaded this endeavor in collaboration with his brother, the venerated Reverend Ignatios. The architect was Sargis, according to a tripartite inscription preserved on the eastern wall pilaster of the church's northern wall: "In your prayers to Christ, do not forget to remember Usta Sargis, the master and builder of this church"(CAE 5, 97). Catholicos Nahapet I Edesatsi, who reigned from 1691 to 1705 in Etchmiadzin, took it upon himself to mediate the longstanding and intractable conflict between Simeon and Catholicos Jeremiah of Gandzasar, whose tenure lasted from 1676 to 1700. As part of the resolution, the self-declared Catholicos Simeon made a solemn commitment that none of his descendants would ever assume the role of Catholicos again. However, in 1705, in direct contradiction to Simeon's previous promise and written commitment, his relative Nerses ascended to the position of Catholicos (a reign that lasted until 1736). Instead of resolving the conflict, Nerses exacerbated tensions with Catholicos Yesai Hasan Jalaliants from Aghvan, who held the position in Gandzasar. By 1707, the situation had escalated to the point where both Catholicos figures were summoned once more to Etchmiadzin. After a thorough examination of the matter, the Catholicos of All Armenians, Alexander I Jughaetsi (who served from 1706 to 1714), excommunicated Nerses and officially declared Yesai as the rightful Catholicos (Leo 1973, 116). However, Catholicos Yesai, recognizing the detrimental impact of their prolonged conflict on the Armenian community, wisely chose to reconcile with Nerses. Following this reconciliation, Nerses' nephew, Israel (who held office from 1728 to 1763), was declared Catholicos within the Yerits Mankanats Monastery. Subsequently, Simeon's nephew, Simeon the Younger Catholicos, also hailing from the village of Khotorashen, assumed the position and reigned until 1819 (Raffi 1964, 229).

The presence of older khachkars within the monastery walls provides compelling evidence of the existence of a cemetery, and possibly even a church or chapel, predating the construction of the main church (Karapetyan 1985, 230). One particular khachkar, positioned within the niche of the northern wall of the northeastern sacristy, bears the following inscription: "1571 year, Mezhlum." In the southern niche of the southeastern sacristy of the small church, an inscription reads: "The Holy Cross of Shahum, Melkum. 1620" (CAE 5, 98).

It's worth noting that in 1854, the monastery had virtually no possessions and was nearly deserted (Leo 1985, 126).

Architectural-compositional examination

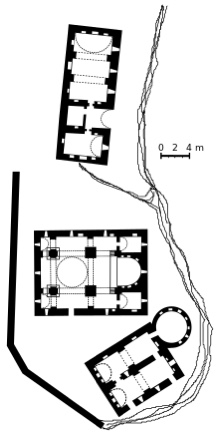

The Yerits Mankants Monastery complex comprises several components, including a church, and a refectory, secular structures, one of which is safeguarded by a corner round tower, likely serving as part of the monastery (Harutyunyan 1992, 398). Additionally, there is a cemetery (Fig. 3). The entire area is enclosed by walls on the southwest and northwest sides, with remnants of their foundations still in existence. The complex is flanked by the steep valley of the Trghi River on its southwest side. The church assumes a central position within the complex, with the refectory situated approximately 15.0 meters to the northeast of the church. The patriarchate residence is positioned near the southeast corner of the church, nestled in a lower area. This arrangement allows the earthen roof of the patriarchate residence to seamlessly extend the southern courtyard of the church, leading towards the valley.

The presence of numerous living quarters, monks' residences, and halls, complete with their fireplaces, all still discernible within the confines of the monastery complex, attests to the substantial congregation that once thrived at the Yerits Mankants Monastery.

The architectural design of the monastery's church adheres to the domed basilica style, characterized by its topographical and spatial layout. The sole entrance to the church is positioned on its southern side. Within the prayer hall, slightly nearer to the western wall, stand four pilasters that support the grand dome. Of these pilasters, the western pair is cross-sectioned, while the pair in the eastern row assumes a square shape, and it is upon these supports that the majestic dome finds its foundation. The prayer hall culminates with the high altar, distinguished by its semicircular wall featuring a total of seven niches. Notably, among these niches, the one on the left draws particular attention due to its opulent ornamentation. The rear wall of the altar showcases the incorporation of earlier khachkars, while its border boasts sculptures reminiscent of intricate stalactites, evoking the decorative style seen in the porches of churches from that era (Fig. 4). The baptismal font exhibits a similar decorative border. Adjacent to both sides of the tabernacle are rectangular storage rooms with two stories. A narrow door, equipped with stone steps that lead from the second-floor sacristy, grants access to the tabernacle. However, it doesn't reach the ground level, necessitating the use of suspended ladders for the remaining descent. This architectural feature, featuring second-floor repositories, can be observed in other late medieval churches throughout different regions of Artsakh. Examples include Tsakhkavank of Tsakuri (Kirakosyan 2023, 111-112), Surb Gevorg of Ptkesberk, and others (Karapetyan 1985, 120).

At the core of the tabernacle lies a preserved solid rock stone. The baptistery retains its traditional location within the north wall. The flooring of the hall has been meticulously paved, with the eastern half remarkably well-preserved.

The church's dome rises, upheld by four square and cruciform pillars interconnected by arches, notable for their arrow-like shape (Fig. 5). Both the dome's drum and the pediment adopt octagonal forms. A single window graces each of the drum's walls, generously illuminating the church's prayer hall. The walls of the drum are adorned with decorative arches, and the cross affixed to the pinnacle of the spire remains in its rightful position.

The grandeur and expansiveness of the church's prayer hall are accentuated by several remarkable features. These include the soaring columns that reach upward, the graceful curvature of intersecting arches, the enchantment of sunlight streaming through the expansive windows of the drum (Fig. 6), the elaborate lithograph with majuscule writing on the stage facade, as well as the presence of numerous large and small khachkars and windows throughout the space.

The church's facades are adorned with meticulously polished stones, except the western side. These stones are embellished with sculpted relief khachkars. The southern facade stands out with its opulent architectural ornamentation, featuring an arched porch and a set and crowned window (Fig. 7). In addition to their decorative role, polished stones are strategically utilized in various structural elements, including corners, pilasters, the arches that connect them, the tabernacle, the dome, the pediments, and the drum, all contributing to the architectural integrity of the building.

The Yerits Mankants Monastery exhibits distinctive compositional characteristics. Notably, the placement of the church's dome is shifted towards the west (Fig. 3). However, this less conventional arrangement goes largely unnoticed due to the architect's ingenious decision to situate the sole entrance to the church on the southern side. Upon entering, visitors are perceptually guided to perceive the dome as being centrally positioned within the prayer hall. Furthermore, the presence of eight arches supporting the dome and the elevated composition of the upper facade of the church bestows an added layer of elegance upon the structure. Upon initial observation, the dome may even appear somewhat smaller in comparison to the main walls of the church. This architectural subtlety, combined with the strategic choice of positioning the monastery on a high elevation, allows the Yerits Mankants complex to be visible from the Jraberd Castle. Considering the original purpose of the monastery, which was to undermine the influence of the Catholicosate in Aghvan and rival the Gandzasar monastery complex, the significance of the elevated location and the soaring architectural design becomes quite evident. The architect also made deliberate efforts to give the church an outward resemblance to the Church of Surb Hovhannes Mkrtich at the Gandzasar monastery.

The refectory of the Yerits Mankants Monastery is a simple structure comprising a dining hall, a vestibule, and a kitchen. Within the dining room, there are niches recessed into three of its walls, while the wall facing the valley is adorned with three arched windows. The dining hall features a vaulted ceiling supported by two vaulted arches. Openings and fireplaces are integrated into the walls (Fig. 8).

The structure designated as the patriarchate residence comprises a hall enclosed by walls that open into the courtyard. Inside this hall, doors lead to dwelling rooms arranged on both sides. These rooms feature openings and fireplaces in their walls, similar to those found in the refectory. The subsequent set of rooms is situated below the level of the south wall of the church and consists of two adjoining rectangular halls (Fig. 3). Further to the left side of the hall and almost entirely subterranean, there lies a sizable hall with a circular layout, which serves as the patriarchate residence. This structure is remarkably unique in its design. The solitary window within this hall offers a scenic view of Jraberd and the picturesque valley of the Trghi River.

A surviving inscription in the monastery suggests that, aside from its other purposes, there was a seminary and various living quarters. The living quarters had basements that served as storage and hiding spaces, but some of these had been damaged or broken over time.

The condition before, during, and after the war

As a fortified monastery, Yerits Mankants Monastery held significant importance in the liberation struggle of Artsakh during the early 18th century.

During the First Artsakh War, when Azerbaijan occupied Gulistan in June 1992, the local Armenian population, numbering around 14,000, embarked on a journey on foot to the Martakert region. Approximately 2,000 to 3,000 individuals from this group made their way through the forests and found refuge within the confines of the Yerits Mankants Monastery. They sheltered there until auxiliary groups arrived.

The structures of the monastery have endured significant damage over time, with some of the secular buildings being either destroyed or reduced to rubble.

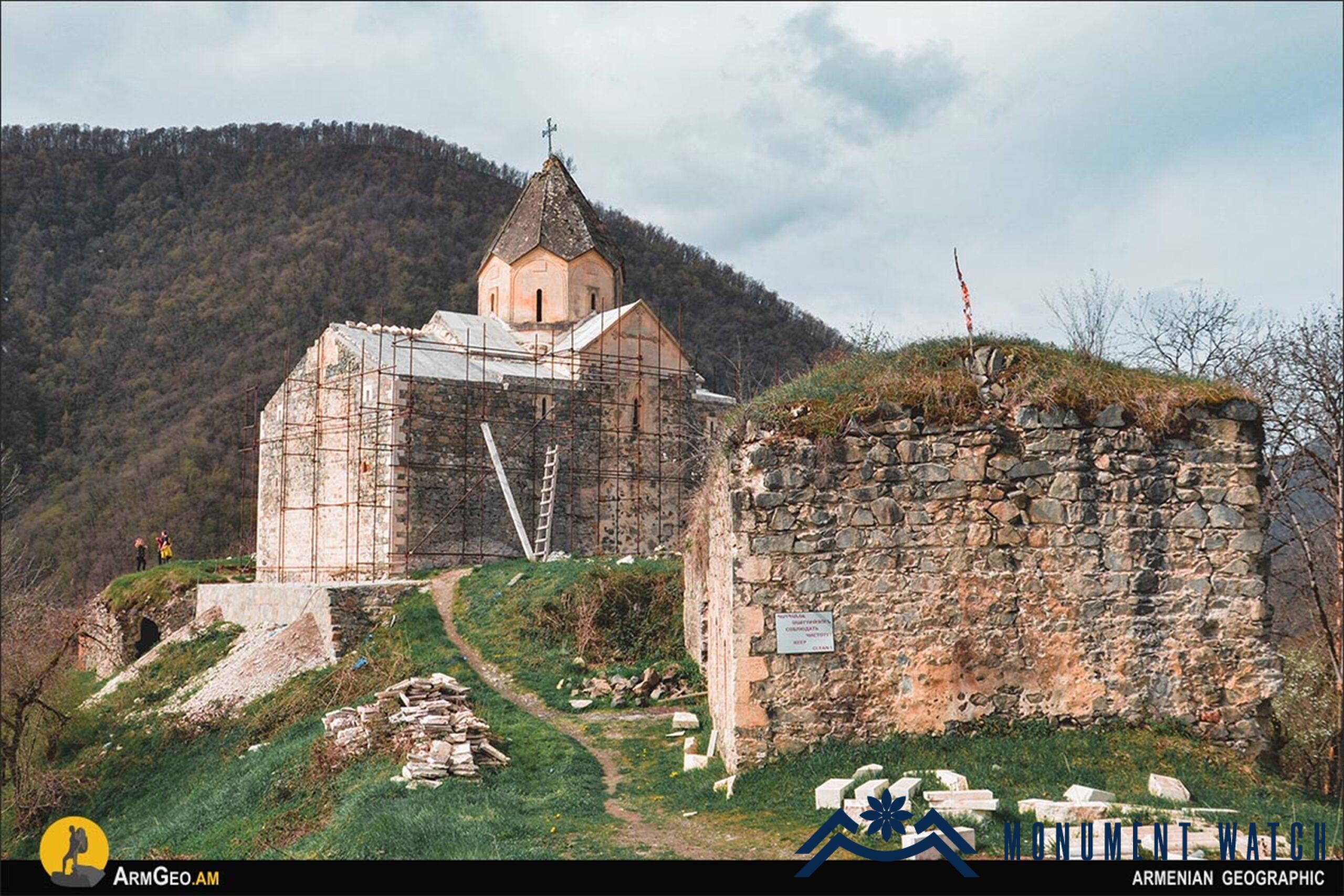

Following the conclusion of the First Artsakh War, efforts towards partial restoration of the Yerits Mankant Monastery began. Work was underway to repair the roof slabs of the church and reinforce the facades (Fig. 9). These restoration efforts were interrupted due to the events of the Second Artsakh War. The proximity of Yerits Mankants Monastery to the border with Azerbaijan has posed challenges for comprehensive research of the complex. Despite its significant historical and cultural value, the monastery remains highly endangered. Urgent measures are needed for preventive fortifications, further research, and restoration efforts to ensure its preservation.

Bibliography

- CAE 5 - Corpus of Armenian Lithography, Issue 5, Artsakh/compiled by S. Barkhudaryan, Yerevan, 1982.

- Leo 1985 - Leo, My Diary. Tartar and Mrav, Leo, Compositions, Vol. 8, pp. 97-140, "Soviet Writer" ed., Yerevan.

- Leo 1973 - Leo, History of Armenia, Leo, Collection of Compositions, Vol. 3, book 2, "Hayastan" ed., Yerevan.

- Karapetyan 1985 - Karapetyan St., two monastic complexes of the 17th century Artsakh, PBH, No. 1, Yerevan.

- Hasratyan 1973 - Hasratyan M., Architectural complexes of Syunik in the 17th-18th centuries, Publishing House of the USSR Academy of Sciences, Yerevan.

- Harutyunyan 1992 - Harutyunyan V., History of Armenian Architecture, 2004, "Luys" publishing house, Yerevan.

- Mkrtchyan 1985 - Mkrtchyan Sh., Historical-architectural monuments of Nagorno Karabakh,"Hayastan" publishing house, Yerevan.

- Raffi 1964 - Raffi, The Melikdoms of Khamsa, Raffi, Collection of Compositions, volume 10, Yerevan.

- Lyuba Kirakosyan 2023 - Kirakosyan L. “Albanization” of Artsakh Monuments as One of the Manifestations of Anti-Armenian Discourse in Azerbaijan։ The Example of Tsaghkavank, Lectures Croisées des Discours Hiatus entre Réalités Sociopolitiques, Récits de Mémoire et Approches Interprétatives Yerevan State University, Department of Translation Studies, Translation Studies: Theory and Practice, International Scientific Journal, Special Issue 1, Yerevan, 108-116.

The Yerits Mankants monastery

Artsakh